AI can sift through large scientific dossiers in minutes instead of months, bridging the divide between research and implementation.

Director General in the Ministry of Health, Dr Patrick Amoth, has urged researchers and clinicians to embrace technology, especially Artificial Intelligence (AI), to help interpret complex health data and improve health outcomes.

Speaking on behalf of the Cabinet Secretary for Health at the inaugural STAR National Science Research Translation Congress in Nairobi on October 22, 2025, Dr Amoth emphasised that “science and research are the backbone of strong health systems and sustainable development,” but lamented that too much evidence remains “underutilised, not informing policy, not guiding programs, and not improving lives as it should.”

He emphasised the potential of Artificial Intelligence (AI) to accelerate regulatory processes and improve health outcomes. Citing delays in registering new maternal health drugs such as heat-stable carbetocin, which could prevent postpartum bleeding deaths, he noted that traditional review systems can take up to a year.

“But with AI, we can scan through large scientific dossiers in minutes instead of months,” he explained. “Technology can help bridge the divide between research and implementation, bringing lifesaving interventions closer to our people.”

The congress, which brought together experts from academia, research institutions, the private sector, media and development partners at the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) in Nairobi, focused on the challenge of bridging the gap between research and its practical application in Kenya’s health sector.

Dr Amoth hailed the congress as “a timely and essential forum” that, he said, “signals a new era of collaboration where research is not only produced but translated, applied, and measured by its impact on people’s health and well-being.”

He further underscored the Ministry of Health’s commitment to strengthening the research-to-policy pipeline, ensuring that policies are grounded in locally generated evidence. He cited the Directorate of Health Financing, Digital Health Policy, and Research as key to promoting evidence-informed policymaking and ethical research frameworks.

Ranking health facilities under the Quality Health Care and Patient Safety Bill will help drive continuous improvement without being punitive

“We continue to enhance collaboration between researchers, implementers, and policymakers,” he said, “and to promote innovation ecosystems through partnerships with national and regional institutions.”

He pointed to data-driven decision-making as a central part of this vision. “We are advancing data-driven decisions using real-time information to improve service delivery and outcomes,” he said, adding that ranking health facilities under the Quality Health Care and Patient Safety Bill will help drive continuous improvement without being punitive.

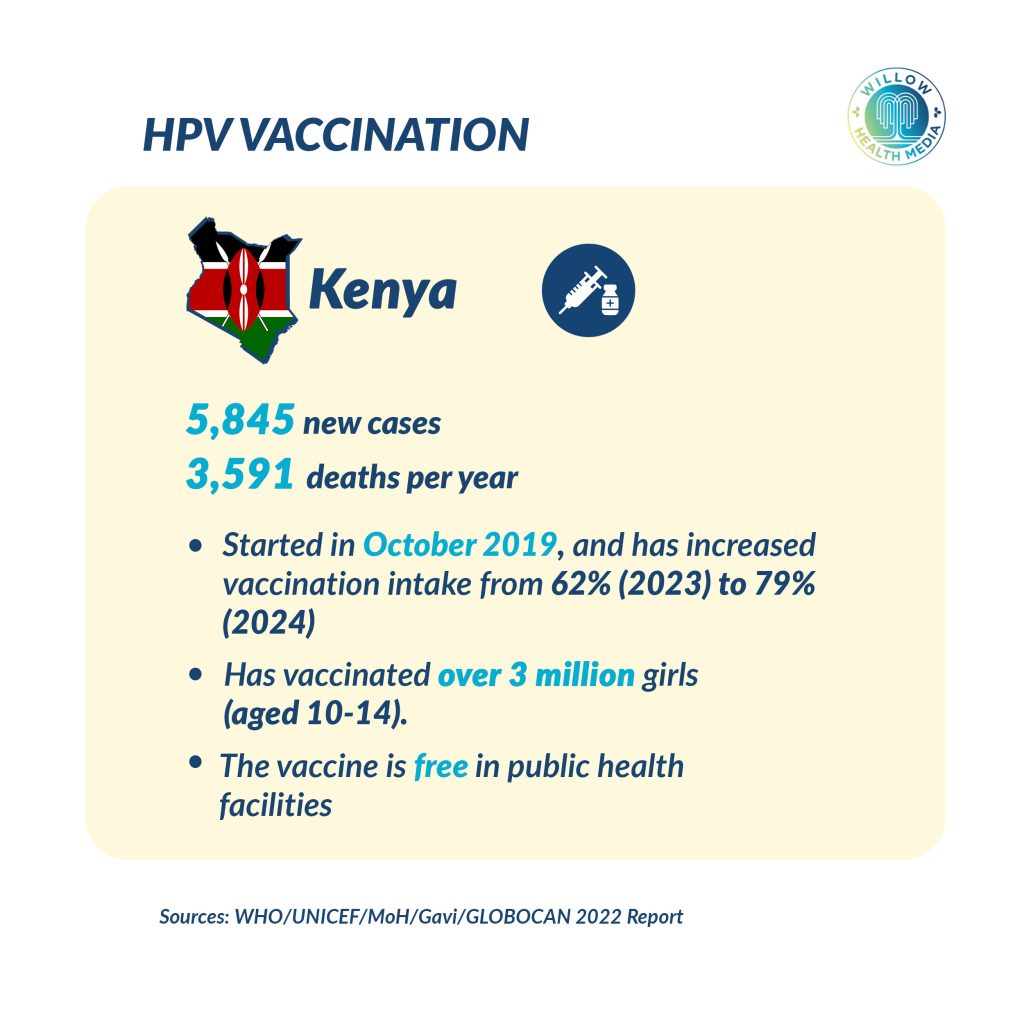

Dr Amoth shared tangible examples of how local research is shaping health policy. He announced that Kenya will transition from two doses of the HPV vaccine to a single dose, a move informed by local evidence that shows it will enhance coverage among girls.

“Our HPV vaccination coverage has dramatically improved,” he reported, noting that first-dose coverage now stands at 60 per cent, up from disruptions during the Covid-19 pandemic, while second-dose coverage has climbed to 38 per cent.

He also revealed plans to introduce a second dose of inactivated polio vaccine at nine months of age, alongside efforts to tackle vaccine hesitancy. He described Kenya’s young researchers as “the future of health research,” urging more investment in capacity building, mentorship, and funding to enable homegrown innovations.

The congress, hosted by APHRC and Radio Africa Group, focused on a question that has long haunted the African research landscape: why does so much scientific work fail to influence real-world change?

“It’s not enough to do research,” declared Paul Ilado, General Director of Radio Africa Group. “Our research must be accessible, understood, and implemented in ways that directly impact public health and well-being.”

Ilado called on scientists and media professionals to collaborate in making research relatable, emphasising that communication is as critical as discovery. “We have unprecedented tools at our disposal, such as social media. We must use them to tell our stories and make our science visible,” he said.

APHRC’s Head of Policy Engagement and Communications, Mamadou Diallo, delivered a sobering statistic: “Up to 83 per cent of research resources are wasted because they are not translated into action.”

Diallo, a seasoned policy analyst, outlined APHRC’s mission to “generate evidence, strengthen research capacity, and engage policy to inform action on health and development.” He urged African institutions to define their purpose before forming partnerships.

“Partnership doesn’t start with an MOU, it starts with why,” Diallo said. “What is our purpose? What keeps people up at night? We must start with that before we talk about collaboration.”

APHRC, founded and led by Africans, now operates across 35 countries, employing over 300 full-time staff, half of them researchers. Its continental mandate, Diallo noted, is “to transform lives in Africa through research.”

Science is not difficult because people lack intelligence; it’s difficult because of how we tell the stories

The need for translation, both linguistic and conceptual, dominated the first panel discussion, which featured health journalist Anne Mawathe, infectious disease expert Dr Loice Ombajo, and Dr Chris Barasa, CEO of the Christian Health Association of Kenya (CHAK).

Mawathe, a veteran journalist, called storytelling “an act of translation between worlds of knowing.”

“Science is not difficult because people lack intelligence; it’s difficult because of how we tell the stories,” she said. “We need to make science feel relevant and human.”

Dr Barasa highlighted the underappreciated role of faith-based health institutions, which he said provide up to 40 per cent of Kenya’s healthcare services.

Barasa urged researchers to think beyond academic publication: “How do we translate research into step-by-step approaches that improve outcomes in hospitals? We lack implementation science platforms to do this.”

He also called for outcome-driven thinking in healthcare: “We run schools based on performance. Why not hospitals? Imagine if we tracked which hospitals deliver better orthopaedic outcomes and used that data to guide care.”

For Dr Loice Ombajo, bridging the gap between science and policy begins with listening. She recounted her experience at the University of Nairobi’s Centre for Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis (CEMA), established during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Dr Ombajo stressed that scientists must engage policymakers “from the beginning, not at the point of publishing results.” This early engagement, she said, ensures relevance and speeds up policy uptake.

“If our research isn’t impacting policy, it’s useless,” she said.

Country Director for Zipline Kenya, Charles Kariuki, shared how the drone logistics company had to counter misinformation when it began operations in Kenya. “People said our drones were spying on women bathing,” he recalled. Zipline countered by engaging local leaders, sharing data-backed impact studies, and maintaining continuous dialogue with regulators and communities.

Professor Silas Oriaso of the University of Nairobi challenged the academic community to rethink how it trains scientists and communicators. “We still have a scientific monologue,” he said. “We need to replace it with dialogue. Scientists and communicators must be equals.”

Daniel Aghan of MESHA echoed that sentiment, describing the symbiotic relationship between journalists and researchers: “For every story not reported, a life is lost. For every story told, a life is saved.”

Aghan called for mutual respect and ongoing engagement through initiatives like “science cafés,” where journalists and researchers discuss emerging issues informally. “We must work together, and not tire of working together,” he said.

Nicholas Etyang, Policy Engagement Manager at APHRC, stressed that research must amplify community voices, not just present data.

“Every research report is a voice of some community,” he said. “Without lived experiences, our reports are incomplete.”

Etyang described projects in Kenya and Malawi that brought adolescent mothers into policy conversations on teenage pregnancy. “Their testimonies moved policymakers more than numbers ever could,” he said.

As the congress drew to a close, health journalist Joyce Mutheu summarised the challenge succinctly: “Your key agenda as a researcher is to move the paper from communication to change.”

She illustrated how an investigative story on gambling, based on scientific studies linking betting to suicide and poverty, led to government action, including a suspension of gambling advertisements and renewed debate in Parliament.

“Work with the end in mind,” Mutheu urged. “If you don’t communicate your findings, they become part of the 80 per cent that’s wasted.”

In his closing remarks, Ilado reminded participants that research, communication, and policy are inseparable parts of the same ecosystem.

“Scientists, government officials, and the media must work hand in hand,” he said. “Together we can create a healthier and more informed Kenya.”