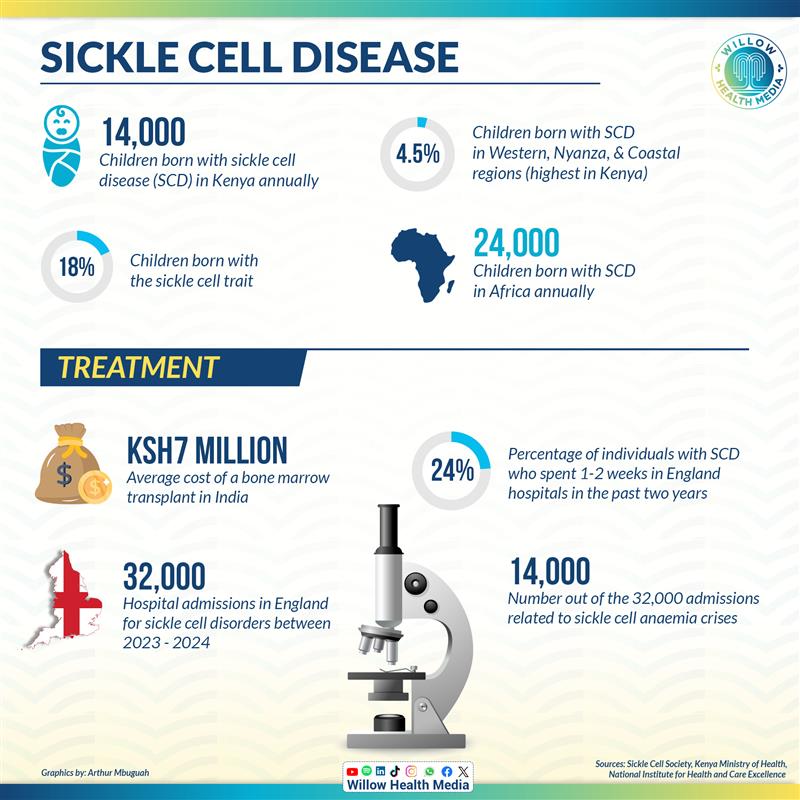

About 14,000 Kenyans are born with sickle cell disease annually — tiny heartbeats carrying an ancient burden with most from Western, Nyanza, and Coastal regions, where the disease passes down like an unwanted inheritance.

A new gene therapy has received regulatory approvals for the treatment of sickle cell disease (SCD), offering fresh hope to people living with this lifelong genetic condition that has left many grappling with chronic pain and limited treatment options, especially in Kenya, where the disease is the commonest blood disorder, according to AMPATH.

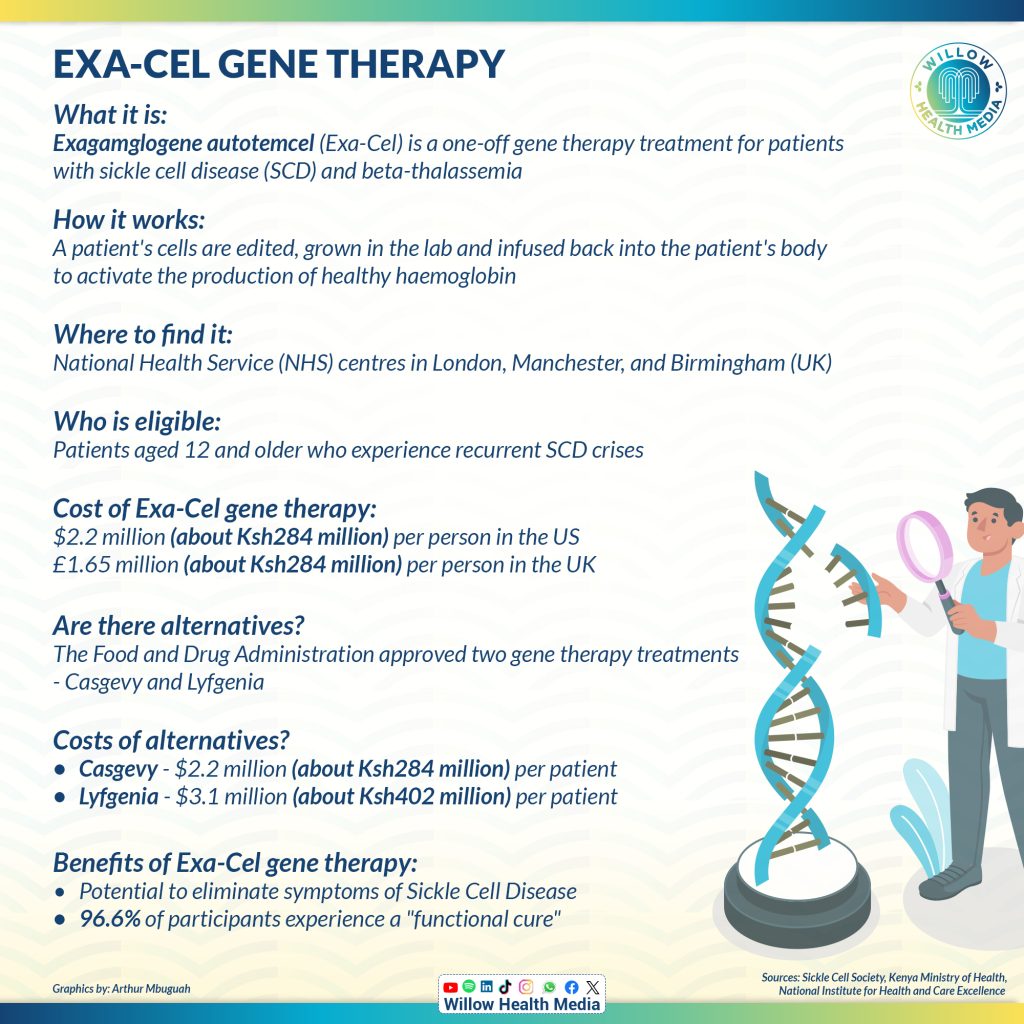

The Exagamglogene Autotemcel (Exa-cel) gene therapy, approved by the United Kingdom (UK) in January this year, is a one-off treatment designed for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD)and transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia (TDT), with recommendation from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Beta-thalassemia is a genetic blood disorder characterised by reduced or absent production of beta-globin, a component of haemoglobin, which is the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen throughout the body.

While some Kenyans with deep pockets manage bone marrow transplant at over Ksh7 million in India, the new gene therapy is 30 times more costly. Majority of Kenyans will thus have to contend with the affordable treatments they’re used to, including pain medication, supplements, vaccines, blood transfusions and hydration and oxygen therapies.

Medications for Sickle Cell Disease are, however, not yet covered under the Social Health Authority (SHA).

Most Kenyans rely on out-of-pocket payments, besides reduced medications provided by NGOs.

Besides the gene therapy, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2023 approved two milestone treatments, Casgevy and Lyfgenia, representing the first cell-based gene therapies for the treatment of sickle cell disease (SCD) in patients 12 years and older.

Casgevy is a treatment for sickle cell disease for patients 12 and older who have repeated pain crises. It’s the first treatment approved that uses CRISPR gene editing technology. Lyfgenia is another treatment for sickle cell disease. It changes blood stem cells to make a special type of haemoglobin that works like normal haemoglobin. This helps prevent red blood cells from changing shape and blocking blood flow.

About 50–90 per cent of children with Sickle Cell die before celebrating their fifth birthday

According to the Ministry of Health, at least 14,000 children are born with sickle cell disease in Kenya annually and about 18 per cent carry the sickle cell trait, with the highest burden in Western, Nyanza, and Coastal regions.

Without proper care, about 50–90 per cent of children with SCD die before celebrating their fifth birthday, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

In England, over 32,000 hospital admissions for sickle cell disorders were recorded, with nearly 14,000 related to sickle cell anaemia, according to the Sickle Cell Society, UK.

Limited treatment options, including the costly bone transparent surgery, leave families struggling with pain, hospitalisations, and a reduced quality of life.

The new gene therapy now offers patients a one-time treatment with the potential for a long-term cure.

Exa-cel is a type of gene-edited therapy that involves modifying a patient’s own cells to correct genetic defects that cause blood disorders such as sickle cell, according to Columbia University Irving Medical Centre.

In the UK, gene editing therapy costs about Ksh284 million per person

Stem cells are collected from a patient’s bone marrow or blood and then modified in a lab using a CRISPR Cas9 gene editing technique to correct genetic mutations that cause sickle cell disease. The goal is to activate the production of healthy haemoglobin.

After editing, the cells are grown and expanded in a lab before being infused back into the patient’s body. These modified cells are designed to produce healthy red blood cells, which can significantly reduce or even eliminate the symptoms associated with blood disorders.

This is the first FDA-approved CRISPR-Cas9 gene therapy for sickle cell disease

Amanda Pritchard, Chief Executive of the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK, termed the development a ‘leap in the right direction’ in the fight against sickle cell disease and is part of a series of revolutionary gene therapies introduced by the NHS England.

According to the New England Journal of Medicine, clinical trials were carried out at multiple international sites. Notably, the CLIMB SCD-121 Phase 3 trial was carried out across 16 locations, including Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, the USA and the UK, where St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital participated in related studies.

The results show that the treatment (exa-cel) may stop the painful crises caused when sickled cells block blood vessels. Almost 97 per cent of patients in the study showed what doctors called a “functional cure,” suggesting many patients might be able to live without sickle cell disease symptoms.

Experts like Prof Bola Owolabi, Director of the National Healthcare Inequalities Improvement Programme at NHS England, termed the therapy a “monumental step forward” in treating sickle cell disorder, especially for patients of African and Caribbean heritage.

This gene therapy technology is not yet available in Kenya… We don’t yet know the long-term effects

Will Kenya embrace this gene therapy? Phionah Obandah, a Genomics Scientist based in Kakamega County and an advocate for sickle cell disease, lauded the new gene therapy, but singled out significant challenges in terms of infrastructure and accessibility in Kenya and across Africa.

“Despite its potential, the treatment requires highly specialised infrastructure, resources that are currently more accessible in countries like the United Kingdom and the United States,” said Obandah.

“This technology is not yet available in Kenya, and it’s important to understand that it is still under clinical trials. We don’t yet know the long-term effects, as we are altering a person’s genetic makeup.”

Suvy Amadi, 36, a sickle cell warrior who thought she would not live past 18 years, welcomed the gene editing therapy “that promises not just to treat the symptoms, but to potentially eliminate the root cause of the disease, offering a brighter future to countless families,” says Amadi who laments at its prohibitive cost.

In the UK, gene editing therapy costs £1.65 million pounds (about Ksh284 million) or $2.2 million (about Ksh284 million) per person in the US.

There is also a combination of legal, ethical, and health expertise for its administration.

Exa-cel gene therapy, Casgevy and Lyfgenia also have prohibitive costs of $2.2 million (Ksh285 million) and $3.1 million (Ksh402 million) per patient, respectively.

Government must allocate more resources to awareness campaigns and for treatment options like gene therapy

Prof Gordon Nguka, a Medical Dietetics and Paediatric Physiology consultant, says while the potential for gene therapy is enormous, there is a need for early screening in areas with high prevalence of sickle cell disease, to ensure that those who need treatment most can access it.

“The government must mobilise enough resources from partners locally and internationally and allocate them to awareness campaigns and, ultimately, for treatment options like gene therapy,” Prof Nguka says. “While it’s a significant investment, the benefits for sickle cell patients could be life-changing.”

Prof Nguka, who is also a lecturer in the Department of Nutritional Sciences at Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, says that in addition to gene therapy, bone marrow transplants also offer curative options for sickle cell disease, although they rely on donor availability.

He says that solving the sickle cell disease problem in Kenya will require a multi-faceted approach, including creating awareness, mobilising resources and improving medical infrastructure.

In western Kenya, many children under five years old die from sickle cell disease because of late diagnosis, healthcare workers not knowing enough about it, and a lack of treatment.

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital opened region’s first dedicated sickle cell care units

AMPATH, a partnership between Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, Moi University, and Indiana University, has helped over 3,000 sickle cell patients of all ages across western Kenya. They provide medicines like Hydroxyurea, Penicillin V, Folic Acid, Proguanil, pain relievers, and vaccines.

Since 2012, AMPATH has trained over 5,000 healthcare workers, screened over 25,000 children, started treatment for 75 per cent of cases they found and examined more than 2,800 patients in blood disorder clinics

On March 13, 2025, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital opened one of the region’s first dedicated sickle cell care units.

In September 2023, Kenya’s Ministry of Health partnered with Novartis to start the Afya Dhabiti Project, which aims to improve early diagnosis, lower treatment costs, and increase access to hydroxyurea medicine.