From relentless droughts and searing heat to catastrophic floods, climate change is not only transforming landscapes but also reshaping health outcomes for millions across Africa.

As global temperatures rise, Africa stands at the frontline of climate change’s most devastating impacts. Though the continent is responsible for less than 4%of global greenhouse gas emissions, its populations and ecosystems bear the brunt of increasingly extreme weather events.

Extreme temperatures and prolonged dry spells left fields barren, leading to widespread food insecurity. According to the Kenya Economic Survey 2023, 3.4 million people faced acute food shortages during the 2017-2018 drought affecting millions across Somalia and Ethiopia too, with children and the elderly suffering the most severe health impacts due to these cycles of drought that have become increasingly severe. The United Nations reported that an estimated 1.4 million children across the region faced malnutrition, leaving them vulnerable to diseases such as pneumonia and diarrheal infections.

Malnutrition weakens the immune system, making it difficult for individuals to fight off diseases like tuberculosis and respiratory infections. With scarce resources to address these challenges, health systems have struggled to adapt to the growing and complex demands posed by the ongoing climate crisis.

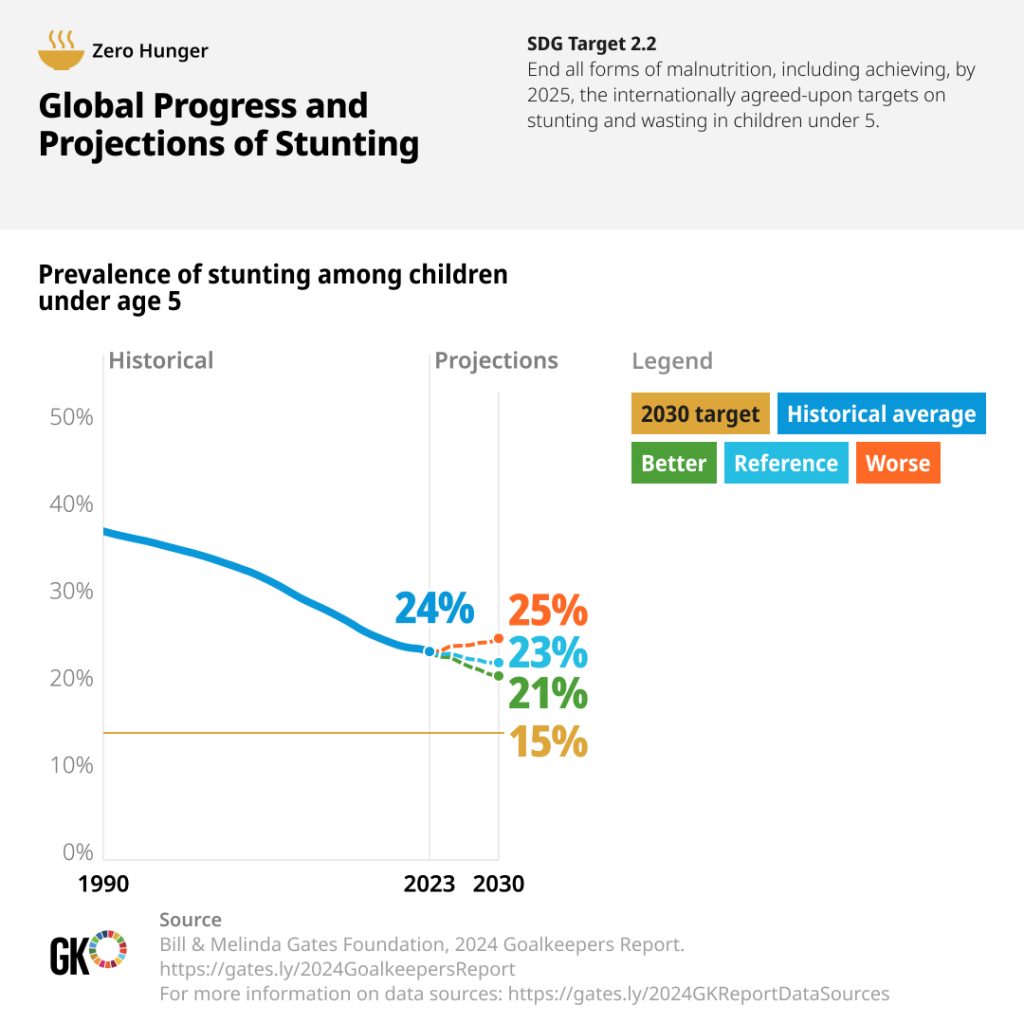

According to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s 2024 Goalkeepers Report, rising temperatures and erratic weather patterns are driving a dramatic increase in malnutrition, with severe implications for the continent’s future. The report estimates that nearly 80 million people across Africa face food insecurity due to climate change, which impacts agricultural productivity, drives up food prices, and worsens malnutrition—especially among children and pregnant women.

With droughts and floods destroying crops and livestock, the threat to nutrition has never been more pronounced, and the report warns that millions of African children face stunted growth and other long-term health issues as a result.

In 2019, Mozambique faced unprecedented devastation from two cyclones in a single season. Cyclone Idai, one of the strongest tropical storms on record in the southern hemisphere, made landfall in March, causing floods that inundated entire communities and displaced hundreds of thousands. The cyclone was followed just a month later by Cyclone Kenneth, which devastated northern Mozambique and southern Tanzania. The back-to-back storms claimed more than a thousand lives, while thousands more lost their homes, livelihoods, and access to essential health services.

Beyond the immediate devastation, the cyclone’s impact lingered through disease outbreaks. Floodwaters contaminated drinking sources, creating fertile grounds for cholera. Mozambique reported over 4,000 cases of cholera in the aftermath of Cyclone Idai, with health workers struggling to provide clean water and sanitation in makeshift shelters. Malaria cases also surged as stagnant pools became mosquito breeding grounds, straining a health system already stretched to its limits.

The 2020 locust infestation that swept through the Horn of Africa offered a stark example of how climate change can trigger cascading crises. Unusually warm and wet conditions linked to climate change created ideal breeding conditions for locusts, which swarmed across Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia in massive numbers, destroying crops and grazing land. With food supplies decimated, millions faced acute food shortages, worsening malnutrition and hunger, particularly among children.

Ethiopia alone saw nearly one million people pushed into severe food insecurity, and aid organizations struggled to keep pace with the rapidly deteriorating conditions. Health workers in the region report that malnutrition-related illnesses have increased in the wake of the locust invasion, as communities wait for the land to recover enough to support crops again.

South Sudan has seen successive years of heavy rains and floods, with extreme weather displacing nearly a million people in late 2020 alone. Mosquitoes breeding in stagnant pools led to a sharp rise in malaria cases, already the leading cause of illness and death in the country. Cholera outbreaks also became a constant threat, as families struggled to find safe drinking water amid swamped conditions.

In West Africa, heatwaves and rising temperatures have become the new normal, putting a direct strain on human health. These heatwaves also intensify the burden of diseases like meningitis, which thrives in hot and dry conditions.

Amid these climate challenges, the Africa-Europe Foundation (AEF) is working to address the intersection of climate change, health, and economic resilience across Africa. Founded to strengthen cooperation between Europe and Africa, the AEF plays a crucial role in advocating for sustainable, climate-resilient development on the continent, particularly in the face of health challenges amplified by climate change.

Paul Walton, the Executive-Director of the Africa-Europe Foundation says their unique contribution is bridging climate and health policy to create a comprehensive approach to Africa’s climate challenges. This integrated focus helps ensure that health impacts are prioritized in climate action plans, fostering resilience where it is most urgently needed.

“Health is the human face of climate change,” he says. “Our people are ahead of our politicians in recognising the intersection between climate and health.” This, he opines, is because certain political leaders struggle with, or avoid complexity.

The Collective Minds Climate x Health Council, led by Foundation S and the Africa-Europe Foundation published a new report From Risk to Resilience: Unlocking Climate and Health Finance for Local Health Adaptation. According to a survey tied to the report launch, 96% of Kenyan respondents expressed that concerns about the health impact of climate change are higher than concerns about the effects of war, geopolitical instability, and global economic pressures. Further, at least three-quarters of citizens living in the Global South think their health has already been impacted by climate change (India: 82%, Brazil: 75%, Kenya: 75%).

At a policy level, the AEF plays an advocacy role, urging leaders to commit more resources to Africa’s climate adaptation needs and promoting fair financing structures. The foundation emphasizes the opportunity for the Africa-Europe partnership to unlock potential in meeting these shared development needs.

“If we try to shift investments and financing towards the kinds of health systems and capacity we need to deal with the impacts of climate change, we need political recognition first,” says Walton.

From a political perspective, however, he says lessons from devastating events and the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, don’t seem to have been translated to policies and financial decisions. This is coupled by operating in silos, where funding and systems work independently depending on the source of funds and differing priorities by countries, which needs alignment in the partnership approach to allow people to work on their core mandates and have a greater impact.

During events like COP27 and beyond, the AEF has been a vocal advocate for climate justice, calling for stronger Africa-Europe investment at the nexus of climate health, enhancing health systems and infrastructure, through a focus on innovative domestic resource mobilisation and the reform of international financial systems.

“African leaders are becoming more articulate and clearer on their expectations of the Africa-Europe partnership, but we should be honest that there is a trust deficit, and work needs to be done for this to be a partnership of equals,” Walton says of the Africa-Europe relationship.

While the world continues to discuss climate solutions, Africa’s populations are living with the immediate consequences of climate change. The health impacts of extreme weather events underscore the need for urgent climate adaptation, such as strengthening health systems, improving early warning mechanisms, and investing in resilient infrastructure.

In a continent where extreme weather is increasingly the norm, protecting health has become a climate priority. Africa’s experience serves as a cautionary tale, demonstrating the urgent need for global action to mitigate and adapt to the growing health impacts of a changing climate.