Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT) analyses the baby’s DNA circulating in the mother’s blood and costs between Ksh45,000 to over Ksh100,000.

When musician Wahu Kagwi saw two lines on her pregnancy test, she didn’t cry tears of joy. She froze.

She had lost two pregnancies before. She was in her mid-40s. Her first born was 16, second born was nine. While she wanted to hope, fear held her tighter.

“My biggest concern was: is this baby healthy?” She remembers. “Because I’d been through the worst before. I just wanted to know what I was walking into.”

That fear would shadow the first weeks of her pregnancy, until her doctor offered her a test she had never heard of, something that could bring clarity to the unknown, “based on my age and the fact that I’ve been told it may be riskier to have a child.”

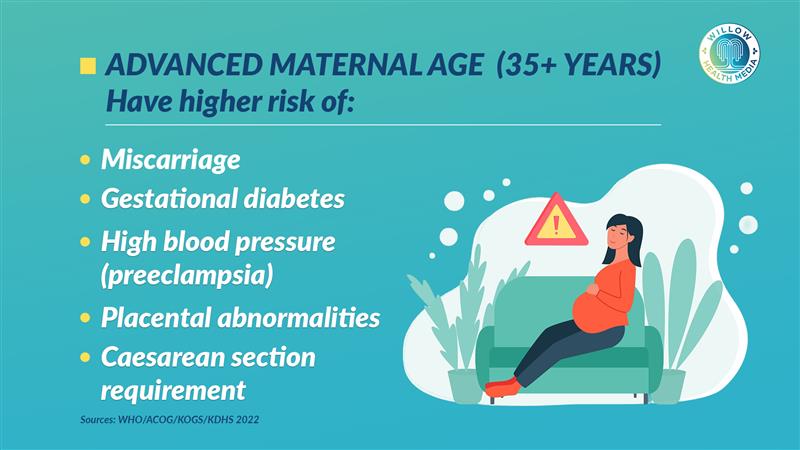

According to Dr Catherine Mutinda, a paediatrician and clinical geneticist, 35 and above are considered advanced maternal age. Most face increased risks of complications including miscarriage, gestational diabetes, high blood pressure, preeclampsia, abnormal placental conditions, and greater likelihood of requiring a caesarean section.

The test was called NIPT—Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing. It would go on to change Wahu’s entire pregnancy experience.

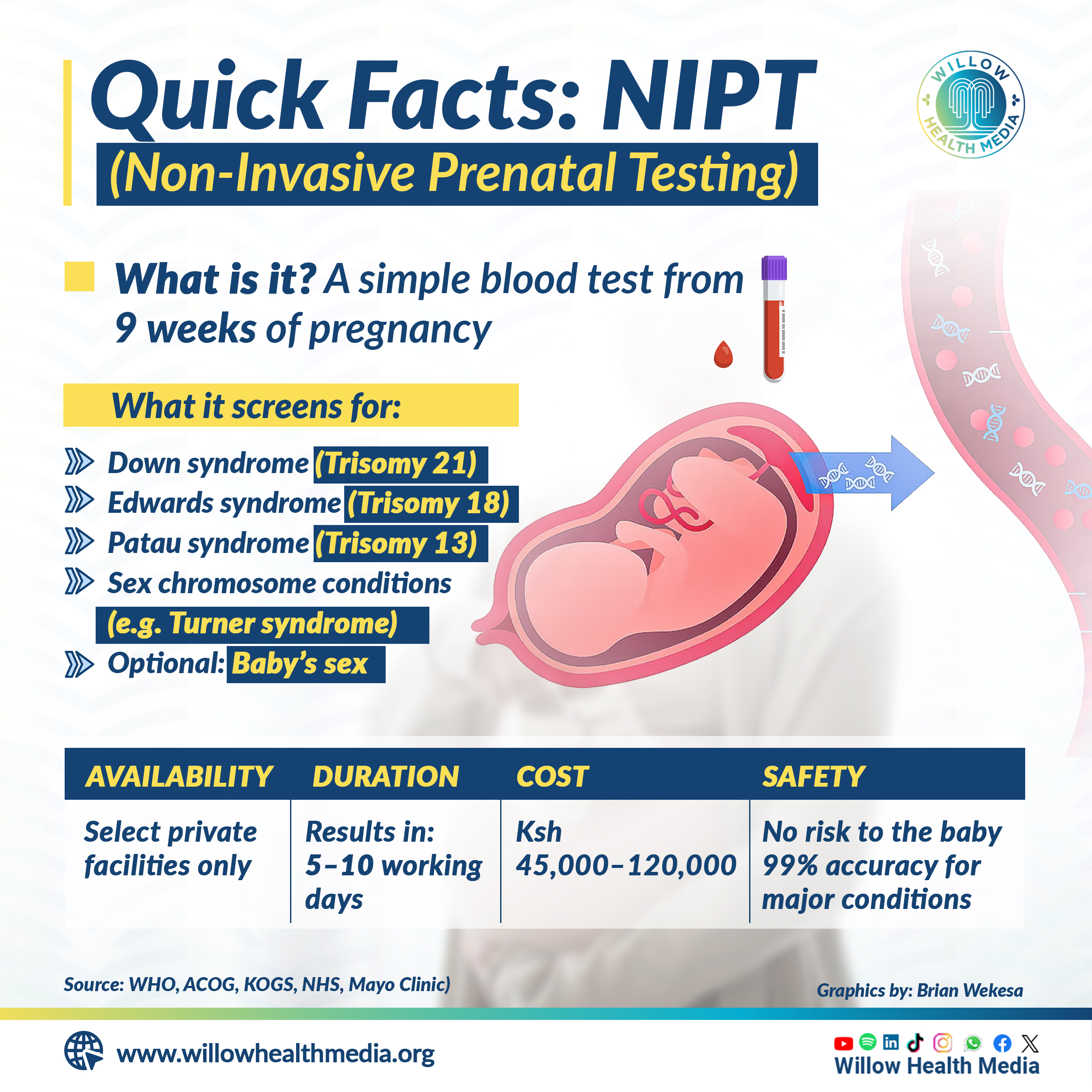

NIPT is done after nine weeks of pregnancy

“I’d never heard of a test like that before,” she says. “The only thing I knew was scanning, the normal things. But the doctor said, ‘If it will help you feel more at ease, we can ‘ I said yes. I want to ”

The test is done after nine weeks of pregnancy when there is sufficient foetal DNA in the mother’s bloodstream. Wahu gave her blood sample. That was all it took.

NIPT works by analysing fragments of the baby’s DNA circulating in the mother’s blood. Unlike older prenatal tests like amniocentesis, offered between 15-20 weeks to women over 35, where a thin needle draws amniotic fluid to check for genetic conditions, NIPT is entirely non-invasive and carries no risk of miscarriage.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) NIPT is over 99 per cent accurate in detecting Down syndrome and also screens for Edwards and Patau syndromes, rare and severe disorders caused by extra chromosomes that often lead to major health issues or early infant loss. It also detects certain sex chromosome conditions like Turner syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, Triple X, and XYY syndrome, which may affect development, fertility, or learning, though many cases go undiagnosed without testing, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

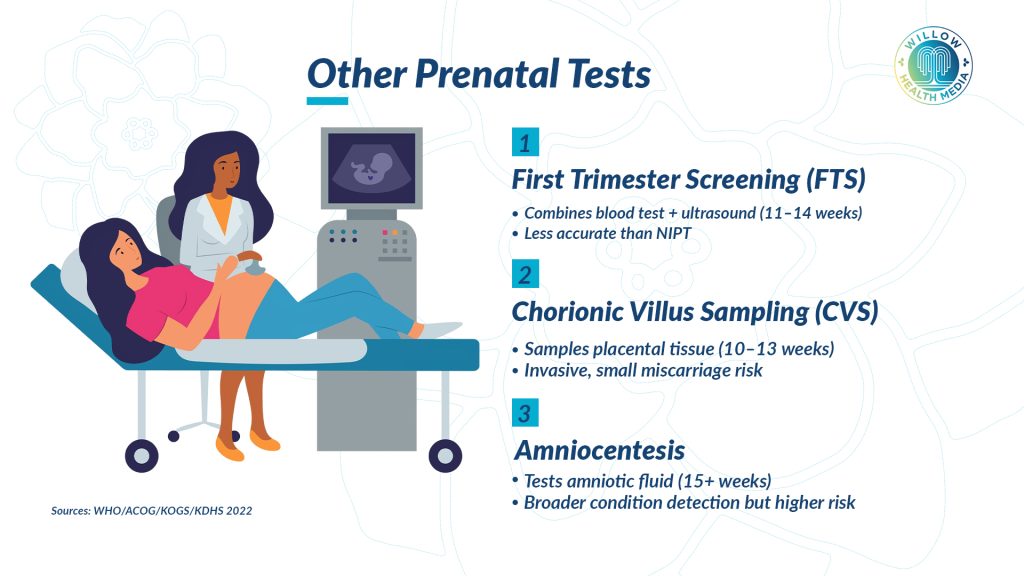

Besides NIPT, other prenatal tests can offer early insights into a baby’s health, though they differ in accuracy, cost, and safety.

First Trimester Combined Screening (FTS), done between 11 and 14 weeks, combines a blood test with an ultrasound to estimate the risk of conditions like Down syndrome. While more accessible and affordable, FTS is less accurate than NIPT.

Early detection of genetic conditions allows families to prepare medically, emotionally

For families needing confirmation, Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS) and amniocentesis are available as diagnostic tests. CVS, done between 10 and 13 weeks, samples of placental tissue to detect chromosomal abnormalities, while amniocentesis—usually performed after 15 weeks—tests the amniotic fluid for a broader range of conditions. Both are invasive and carry a small risk of miscarriage, but they offer definitive answers.

NIPT stands out as a safer, highly accurate screening test that can be done as early as nine weeks, making it a valuable option for early, non-invasive insight.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, early detection of genetic conditions through tests like NIPT allows families to prepare medically, emotionally, and logistically, enabling closer monitoring, timely therapies, and informed decision-making that can significantly improve long-term outcomes.

“The baby’s DNA is in the mother’s bloodstream from early pregnancy,” explains Dr Mutinda. “We can analyse that DNA through a simple blood draw and screen for major chromosomal conditions without ever touching the baby. That’s the power of NIPT—it’s safe, accurate, and offers clarity early on.”

“It was interesting for me because I’m like—the baby’s DNA is just randomly floating in my blood? Like, really, you’re not going to get to the baby?” Wahu says, laughing. “Now I know the ‘tois’ DNA is somewhere in my bloodstream.” But the calm brought by early clarity came with a steep price.

According to the Kenya Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society (KOGS), access is limited with only about five per cent of women receiving it, mostly from private hospitals in Kenya. The cost is also prohibitive, with diagnostic labs ranging between Ksh80,000 to 120,000.

‘The costs were crazy,’ says Wahu of the initial cost of Ksh120,000

“The costs were crazy,” says Wahu of the initial cost of Ksh120,000. “I was willing to do it because it was very important to know.”

According to Dr Mutinda, “These tests are available in Kenya, but mostly in private hospitals. The cost is a huge barrier for most families, and coverage under public healthcare is still lacking. We urgently need our health policies to catch up with the science.”

NIPT is expensive in Kenya because the technology is imported and not covered by insurance, making patients bear the full cost. Most hospitals and laboratories send NIPT samples abroad, mainly to the UK and India. While both offer reliable results, India is more affordable with some tests ranging between Ksh.45,000 and Ksh.60,000.

NIPT entered the Kenyan market following global breakthroughs in genetic medicine, rising demand from informed, urban mothers seeking safer and earlier prenatal screening, and the push by private hospitals to provide advanced, world-class healthcare services.