Black Tax reduces the ability of the working class to invest, save or manage their own money – David Kariuki, Financial advisor

By Nancy Nzau

‘Black Tax’ is the financial assistance a working or well-off family member regularly dishes out to siblings and relatives. Mostly, it’s to meet bills related to food, rent, education to healthcare.

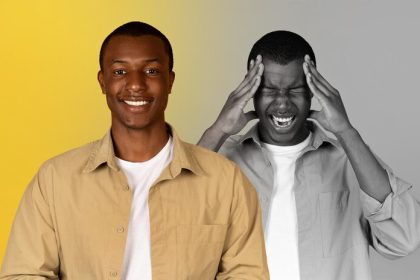

Helping as part of ‘African Socialism’ is laudable besides the feel-good-effect from philanthropy. The downside, however, is that Black tax can be financially crippling, slows personal development, delays life’s milestones, shatters dreams, lowers self-esteem, and affects health. Especially mental health. Or aggravates underlying health conditions. Think hypertension. Diabetes. Stress. Anxiety. Depression. Alcoholism. Insomnia. Heart conditions. Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Ulcers.

The term ‘Black tax’ originated from South Africa, but even in Kenya, most are familiar with the ‘bonds of burden’; how modest success attracts begging bowls from relatives living 100 metres below the poverty line. While some cases are genuine – from historical and socio-economic inequalities – rural leeches also hover around, nagging with reminders of how their father dropped out of District Education Board (D.E.B.) nursery school ‘so that your dad could school.’

What is hardly addressed, though, is how Black tax negatively impacts the health of the giver: chronic worry, burnout, exhaustion and family obligations result in lack of work-life balance and social withdrawal, for instance.

The debate on Black tax was sparked on social platform X by content creator Mwende Susu several months ago when she tweeted: ”…Black tax is you earning the same money as your peers, and while they can save and invest and grow, you’re left behind in the same position because you’re supporting your entire family, and as the years move, the separation becomes wider.”

Dominic Aseka responded how Black tax “drains” him to “the bone”. “It has been 15 good years, and Lord, I am tired.” Reached for comment, Aseka told Willow Health that his father helped his relatives and when he died, elder cousins educated him, and it was now his “turn to pay the tax. It is what it is.”

Aseka says his share of Black tax goes to educating his relatives and financially supporting his mother. “I have dreams put on ice that I’m yet to fulfil. But I never catch a break,” he says, adding that he does not regret helping as it is “a necessary burden.”

Black tax, however, is not something people pay willingly. Social media satirist Elsa Majimbo confessed to hating Black tax with all her heart.

The 23-year-old, who shot to fame for her funny videos during the 2020 pandemic lockdown, lamented about a certain relative who has “been asking my dad for money way before I was born” and now the same relative is asking her for money. “I’m not feeding your habit,” she posted.

Paying Black tax gets worse for those in the diaspora as demands grow bigger, more urgent and with higher financial burdens.

The 2021 Diaspora Remittance Survey by the Central Bank of Kenya showed that annual support to nuclear family members averages $4,000- $6,000 (Ksh520,000- Ksh780,000). The money is for buying food, household goods and domestic bills, medical and education expenses, rent and ceremonies, clothes and farming needs.

Kenyans in cities also send money to rural folk, and according to Financial Deepening Sector- Kenya Survey, the bulk of the money goes to supplement domestic budgets, education, and healthcare.

Black tax mostly affects older siblings, with the firstborn as the worst hit from ‘intense feelings of familial responsibility’, notes Irvin D. Harris and Kenneth I. Howard in Birth Order and Responsibility.

Some take additional jobs and side hustles, thus limiting opportunities for leisure, self-care, or socializing, leading to loneliness which corrodes mental health. Working too hard for others has been known to diminish job satisfaction, leading to feelings of resentment or frustration, contributing to mental strain and depression.

Take Zeth Matara, a teacher in Nairobi’s Kahawa West. He trousers Ksh20,000 in monthly salary, which is hardly enough for his own needs, yet he must educate two younger sisters in university and a brother in a polytechnic “or else their brains and potential will go down the drain. My parents are unemployed and poor. I feel like I am at the end of my tether.”

Like Aseka, Matara experiences a sense of helplessness and extreme stress from budgeting constraints. He has been forced to borrow, take loans and recently held a fundraiser on Facebook.

Chronic financial pressure leads to financial insecurity, increased stress levels manifested in panic attacks, anxiety disorders besides straining family dynamics. It can also trigger self-blame, guilt, and feelings of being overwhelmed. Counselling psychologist Ronald Alosa says Black tax can be a source of misery irrespective of birth order.

“Most times, it is a subconscious, deep-seated sense of responsibility, a kind of payback for sacrifices made by previous generations or family members,” he says.

The burden of responsibility can also aggravate substance abuse in drugs and alcohol, and Alosa adds that it can also bring anger, fear and shame.

Fred Odongo, 45, a newspaper production plant operator from Siaya County, pegs his increased smoking and drinking to shouldering financial contingencies outside his control for the last 20 years.

See, Odongo got his first job in his 20s, but his parents’ early retirement came with bouts of opportunistic illnesses. The need to help quickly morphed into guilt, stress, helplessness and anxiety.

“My grandmother is also often sick, and we fundraise for treatment every fortnight, along with money for food, house help and other basic needs,” laments Odongo. “Add that to my own needs, and I’m stuck in a rat race. I now know why men die early,” Odongo philosophizes. “I drink and smoke too much because of this huge burden on my shoulders.”

Black tax drags down one’s ambitions including home ownership, investing or pursuing education, resulting in feelings of low self-worth. Odongo often feels the decks are stacked against him and “the weight is overwhelming. I look back over ten years, and I haven’t much to show for it, save for a mud house in the village.”

Financial advisor David Kariuki, says Black tax reduces the ability of the working class to invest, save or manage their own money.

“Like tailwinds, Black tax drags you backwards,” says Kariuki. “It keeps the most successful in a family tied to responsibilities they didn’t create. A common example is educating an uncle’s five children when you have none. It’s one of the reasons many Africans will never build generational wealth.”

Black tax thus reduces one’s income, creating an ideal environment for financial stress that triggers increased irritability, sadness, lethargy and insomnia. Some may eat too little or too much or engage in self-destructive behaviours like drug and alcohol abuse or gambling. It may lead some to live beyond their means, increasing debt, further exacerbating financial and emotional strain.

For Miriam Kyalo, 26, a baker at Kariobangi Light Industries in Nairobi, Black tax often leaves her in an emotional whirlwind, prone to anger outbursts and “a constant deep feeling of sadness.”

“I cannot think of starting my own family. My mother has forced me to care for her and the daughter of my elder sister who is unemployed and too lazy to hold a job. I sense anger when I tell them I don’t have money. It has even made me scared to say ‘no’. Most of my stress comes from Black tax.”

A 2024 Study titled Immune-neuroendocrine patterning and response to stress published in the journal Brain, Behaviour and Immunity found that financial stress is detrimental to diabetes, arthritis, heart diseases and schizophrenia, according to lead researcher Odessa S. Hamilton.

To make matters worse, many men avoid seeking help from cultural and societal stigmas on the face of financial burdens straining the prioritization of healthcare. The feeling of helplessness and inadequacy exacerbates underlying conditions.

How did we get here? Well, Dr Eric Kioko, a social anthropologist at Kenyatta University, says Western countries escaped Black tax as they transitioned from subsistence agriculture to industrialisation.

“Responsive governance policies played an important role in setting up formal social welfare systems, allowing long-term planning and addressing evolving challenges, contributing to a fair economic growth for every citizen,” explains Dr Kioko.

In contrast, he says, Kenya’s colonial evolution lacked industrialisation, contributing little to employment and other opportunities while relying on small-scale farming and inefficient businesses. This, on the face of high cost of living, will see millions facing poverty and thus relying on relatives and personal networks for social welfare instead of well-structured institutions.

”Until sustainable institutional and economic structures emerge” he warns, “Black tax will always be a reality.”

Victor Njuguna, a boda boda operator says he has a simple way of balancing Black tax and mental well-being: “If I don’t have money, I don’t feel bad for not helping. And when I send my relatives money, I don’t dictate what they do with it, and I never think about it again. I also never loan money. I only give a sum I am comfortable losing.”

Alosa says paying Black tax can be rewarding, but can also leave one physically, emotionally, and financially miserable after “putting your own progress on hold, often with little recognition or external support.”

Alosa advises people to build up a support network with close friends, trusted family members, or counsellors, to talk through feelings of guilt, shame or anxiety as “empathy and advice can make a huge difference. A healthy balance between being helpful and self-care without sacrificing your own well-being can restore a sense of balance and prevent resentment from building up.”

True. Black tax is an enemy of personal progress

Great article from a great writer. The relevance of this article cannot be underlined enough.

The skills continue improving.

We look forward to a book, sooner or later.

Excellent piece so informative especially during today’s economy