HPV vaccine continues to be the single most powerful and effective tool for protecting women and girls against cervical cancer.

More than one million cervical cancer deaths have been prevented worldwide, and an estimated 86 million girls are now protected against human papillomavirus (HPV), the leading cause of cervical cancer, following an aggressive three-year push by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, to administer vaccines in lower-income countries.

The achievement, announced on the first-ever World Cervical Cancer Elimination Day, held on November 17, 2025, is a significant step in the global fight against one of the deadliest yet most preventable diseases affecting women.

“Every two minutes, a woman dies from cervical cancer, a disease that is both devastating and largely preventable,” said Dr Sania Nishtar, Gavi CEO.

Cervical cancer remains the fourth most common cancer in women globally, claiming 350,000 lives in 2022, with 90 per cent of them in low- and middle-income countries. Africa shoulders the largest burden, with over 76,000 deaths every year driven by low screening rates, limited treatment services, and higher HIV prevalence, which increases cervical cancer risk six-fold.

However, studies have shown that vaccination against HPV, the virus responsible for up to 90 per cent of cervical cancer cases, reduces infection rates by up to 98 per cent.

In 2023, Gavi launched one of the most ambitious vaccine campaigns in its history: to protect 86 million girls from cervical cancer. That target has now been reached ahead of schedule, propelled by “incredible commitment from countries, partners, civil society, and communities,” said Dr Nishtar. “This collaborative effort is driving major global progress towards eliminating one of the deadliest diseases affecting women.”

Supply shortages, poor awareness and limited delivery systems kept the vaccine out of reach

But while global momentum accelerates, Kenya’s own progress presents a mix of urgent need, incremental strides and persistent gaps.

Yet a decade ago, the HPV vaccine, the single most powerful prevention tool, was scarcely reaching the girls who needed it most. Global coverage stood at 9 per cent in 2014, and a shockingly low 4 per cent in Africa. Supply shortages, poor awareness and limited delivery systems kept the vaccine out of reach.

By 2022, Gavi-supported efforts had increased access, protecting over 13 million girls, but global coverage remained low at 14 per cent, and 15 per cent in Africa. The launch of Gavi’s HPV programme in 2023 changed everything.

By the end of 2024, African HPV vaccine coverage had risen to 44 per cent, surpassing Europe’s 38 per cent, while overall coverage across Gavi-eligible countries rose from 8 per cent in 2022 to 25 per cent in 2024.

The campaign’s success, now preventing 1.4 million future deaths, represents one of the largest coordinated women’s health interventions in history. As more than 50 countries introduce the vaccine by the end of 2025, Gavi-supported nations will account for 89 per cent of all cervical cancer cases globally, making high coverage essential.

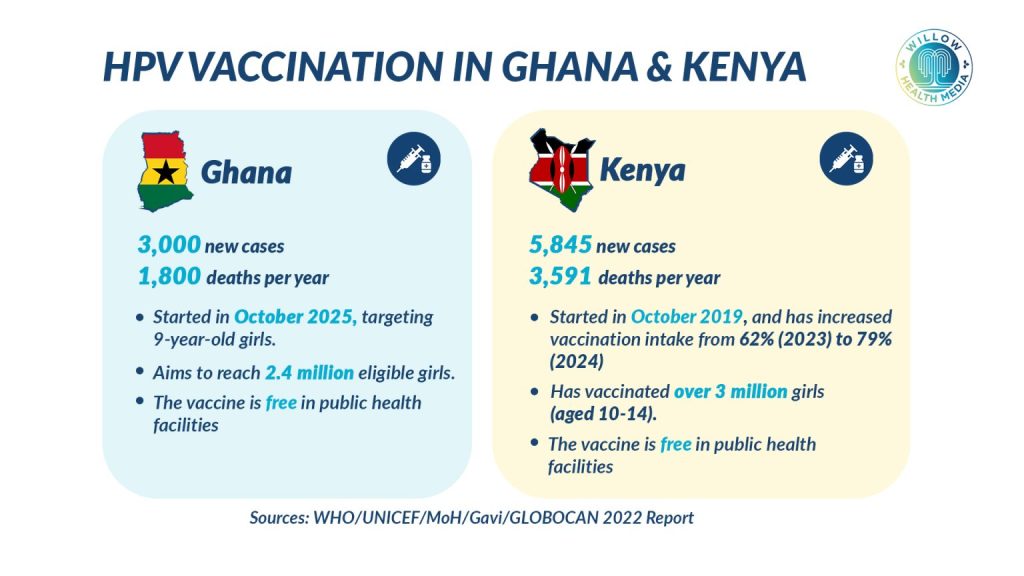

Kenya remains one of the countries with an alarmingly high cervical cancer burden. According to the cervical cancer Elimination Planning Tool (2025) published by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Kenya recorded 5,845 new cervical cancer cases in 2023, with 3,591 deaths. The age-standardised incidence rate was 32.8 per 100,000 women, while the mortality rate stood at 21.4 per 100,000, among the highest in East Africa.

IARC projections show the crisis could worsen dramatically if current trends persist. Between 2020 and 2070, cervical cancer could claim 611,973 Kenyan women, rising to 2.1 million deaths by 2120 without large-scale intervention.

But the same analysis offers hope: if Kenya achieves the WHO elimination strategy of 90 per cent HPV vaccination, 70 per cent screening, and 90 per cent access to treatment, the country could save 1.89 million lives by 2120 and eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem within the same timeframe.

The HPV vaccine is both safe and highly effective, averting 17.4 deaths for every 1,000 children vaccinated. In settings like Kenya, where screening and treatment access remain uneven, the vaccine is an unparalleled game-changer.

Barriers to effective vaccine coverage include hesitancy, social norms, mistrust and lack of knowledge and access

Kenya introduced free routine HPV vaccination in 2019, targeting girls aged 10-14 through school outreach and health facilities. But despite this, coverage remains worryingly low.

A 2024 research paper by the Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) showed that only 26 per cent of eligible girls in Kenya had received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine in 2022. This figure sits far below the WHO target of 90 per cent and lags behind the average in African Gavi-supported countries.

The random survey targeting parents and caregivers of preadolescent girls highlighted hesitancy toward the HPV vaccine, knowledge about HPV and the vaccine, social norms about vaccination, access to and mistrust in vaccine information and institutions as barriers to effective coverage.

Several counties report lower vaccination rates, hampered by vaccine hesitancy, misinformation, religious resistance, logistical challenges, and the lingering effects of Covid-19 pandemic disruptions.

The Kenya elimination scenario report underscores the massive investments required to reverse the trend. Implementing a one-dose HPV vaccination schedule and twice-lifetime screening over the first decade would require $89.8 million (Ksh11.6 billion), 9.4 million vaccine doses, and 2.1 million HPV tests.

Yet the long-term returns are enormous: every $1 (Ksh129) invested yields $52.15 (Ksh6,745) over 30 years, rising to $162.69 (Ksh21,025) over 50 years, largely due to avoided deaths, improved productivity and reduced treatment costs.

Cervical cancer typically affects women in the prime of their lives, including mothers, caregivers, and income earners. The social and economic consequences ripple far beyond individual households. Without urgent intervention, Kenya may miss the global elimination timeline by decades.

HPV vaccination is one of the most cost-effective public health interventions available today. The vaccine’s prevention potential is highest when delivered before sexual debut, making early vaccination between 9-14 years critical.

Already, the government is taking steps to cover the vaccination deficit. Director General in the Ministry of Health, Dr Patrick Amoth, recently announced that the ministry is shifting from two doses of HPV vaccine to a single dose, based on locally derived data showing that the move will promote better coverage.

Speaking during the Star National Science Research Translation Congress in October, Dr Amoth said Kenya’s HPV vaccination coverage has dramatically improved despite Covid-19 pandemic disruptions, “because we use the school-based approach. Our first antigen is at 60 per cent, and our second dose, which was in a single digit, is now at 38 per cent.”

Dr Amoth stated that using the single antigen regimen will make it possible to cover more girls quickly, “And therefore make the dream of the global community and the country to make cervical cancer a thing of the past by 2030.”