What makes DVT particularly dangerous is how silently it creeps; many patients experience mild symptoms or none at all, until the condition becomes severe or fatal

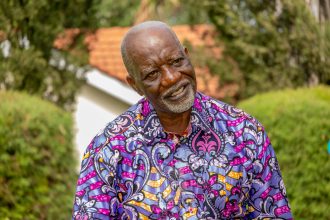

Former Kenyan Prime Minister Raila Odinga had a long list of ailments that contributed to his final demise. Among them were diabetes, brain bleed, chronic kidney disease, high blood pressure, and Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT).

Raila was undergoing Ayurvedic treatment before suffering a sudden cardiac arrest, from which he did not recover, on October 15. His sudden demise has drawn attention to Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT), a potentially life-threatening condition that remains little understood by many.

DVT is a blood clot disorder that often develops silently. According to Dr Bernard Gitura, a cardiologist at Kenyatta National Hospital, DVT occurs when a blood clot forms in the deep veins of the body, usually in the legs, thighs, or pelvis.

“In simple terms, DVT is when you have a blood clot in your deep veins,” he explains.

“The most serious are those that occur in the veins deep inside the muscles, particularly in the legs. If a clot breaks off and travels to the lungs, it can cause a pulmonary embolism, which can be fatal.”

What makes DVT particularly dangerous is how silently it develops. Many patients experience mild symptoms or none at all until the condition becomes severe.

“The first sign is often one-sided swelling,” says Dr Gitura. “You’ll notice that one leg, usually the calf or thigh, becomes swollen, warm, and painful. Sometimes the skin changes colour and it may appear reddish or purplish, depending on your skin tone.”

He cautions that any unexplained swelling in one leg should be treated as a red flag and checked immediately. “If DVT is not treated early, the clot can travel to the lungs and cause pulmonary embolism. That kills fast,” he warns.

Prolonged immobility, such as bed rest after surgery, long hospital stays, or sitting throughout long flights or road trips, is a leading cause of DVT

While anyone can develop DVT, certain groups face higher risks. Age is one of the biggest factors. “The risk increases after age 60,” says Dr Gitura. “But even younger people can develop it, especially if they are inactive or have other medical conditions.”

Prolonged immobility, such as bed rest after surgery, long hospital stays, or sitting on long flights or road trips, is a leading cause. “When you’re immobile, blood flow in your legs slows down. That’s when clots can form,” he says.

Other common risk factors include Injuries to the legs, especially fractures or trauma; Major surgeries, particularly orthopaedic or abdominal procedures; chronic illnesses such as heart failure or cancer; pregnancy and hormonal contraceptives, which can increase clotting risk; obesity, smoking, and poor diet, all of which affect blood circulation.

“Cancer patients are especially vulnerable,” adds Dr Gitura, as cancer treatments can make blood thicker and more likely to clot.

The good news, Dr Gitura notes, is that diagnosing DVT is relatively straightforward. “Once a doctor suspects DVT, they will perform a physical exam and order a Doppler ultrasound. This scan can detect if there’s a clot blocking blood flow in the veins.”

Early diagnosis, he says, can mean the difference between recovery and fatal complications. “Once we confirm DVT, we start treatment immediately to prevent the clot from growing or moving.”

Traditionally, DVT treatment involved hospital admission and blood-thinning injections for several days, followed by months of oral medication. But medical advances have changed.

“Today, we have newer oral drugs that are as effective as injections,” explains Dr Gitura. “Many patients can now start treatment and go home the same day, without needing admission.”

Treatment typically lasts between three to six months, depending on the severity. “It’s not a quick fix,” he cautions. “Patients must take their medication exactly as prescribed and attend follow-up appointments.”

Resting the affected leg in the first few days is essential to prevent the clot from dislodging. “We encourage rest for one to two weeks. After three to five days of treatment, we usually allow patients to start moving around gradually.”

Treating DVT in Kenya remains costly for many patients, especially those without medical insurance. Depending on the medication prescribed, treatment can cost tens of thousands of shillings per month. The older and more affordable drug, warfarin, costs roughly Ksh1,000 per month, but requires regular International Normalised Ratio (INR) blood monitoring, which adds to the expense.

People often confuse DVT with normal leg pain or arthritis, and only go to hospital when it is advanced

Newer, easier-to-manage drugs known as direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs)are considerably more expensive, costing anywhere between Ksh2,000 to Ksh17,000 per pack. For more severe cases requiring injectable options, patients may spend up to Ksh26,000 for a 10-day dose.

Considering that DVT treatment typically lasts three to six months, the total cost can easily exceed Ksh50,000, putting effective care out of reach for many Kenyans who rely on public hospitals or out-of-pocket payments.

DVT prevention, Dr Gitura emphasises, is largely about staying active and managing health risks. “One of the biggest risk factors is immobility,” he says. “So, after surgery or long travel, move your legs, stand up often, and avoid sitting for too long.”

Other simple preventive tips include stretching and walking during long flights or car rides, avoiding crossing legs for long periods, wearing compression stockings when recommended, staying hydrated, maintaining a healthy weight, and controlling chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes.

“Being mobile is the most effective way to prevent DVT,” he stresses. “Even small movements, like flexing your feet or standing up every hour, can make a difference.”

Despite its seriousness, DVT remains underrecognised in Kenya. “We treat DVT cases almost every other day at the hospital,” says Dr Gitura. “But many Kenyans have never heard of it. People often confuse it with normal leg pain or arthritis and only come to the hospital when it’s advanced.”

He adds that raising public awareness is now a key part of cardiovascular health campaigns. “We want people to know that DVT is preventable and treatable. What kills is delay.”

Globally, thrombosis remains a major but often overlooked health threat responsible for 1 in 4 deaths worldwide. According to the World Thrombosis Day campaign, about 60 per cent of venous clots develop during or after hospitalisation, making hospital-associated clots one of the leading causes of preventable hospital deaths. Each year, an estimated 10 million cases of hospital-related clots occur across both low- and high-income countries.

In Kenya, local data reflect a similar concern: a study at Kenyatta National Hospital found that among 168 high-risk medical inpatients, the prevalence of venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT), was 18.5 per cent, underscoring the need for greater awareness, early diagnosis, and preventive care.

Deep Vein Thrombosis may be silent, but its effects can be fatal. Recognising the warning signs, seeking timely medical care, and taking simple preventive steps can be the difference between life and death.