Dr Hellen Barsosio has pledged to fight maternal and infant deaths by pushing for wider access to lifesaving vaccines like the maternal jab for viral pneumonia, which will soon be available in Kenya.

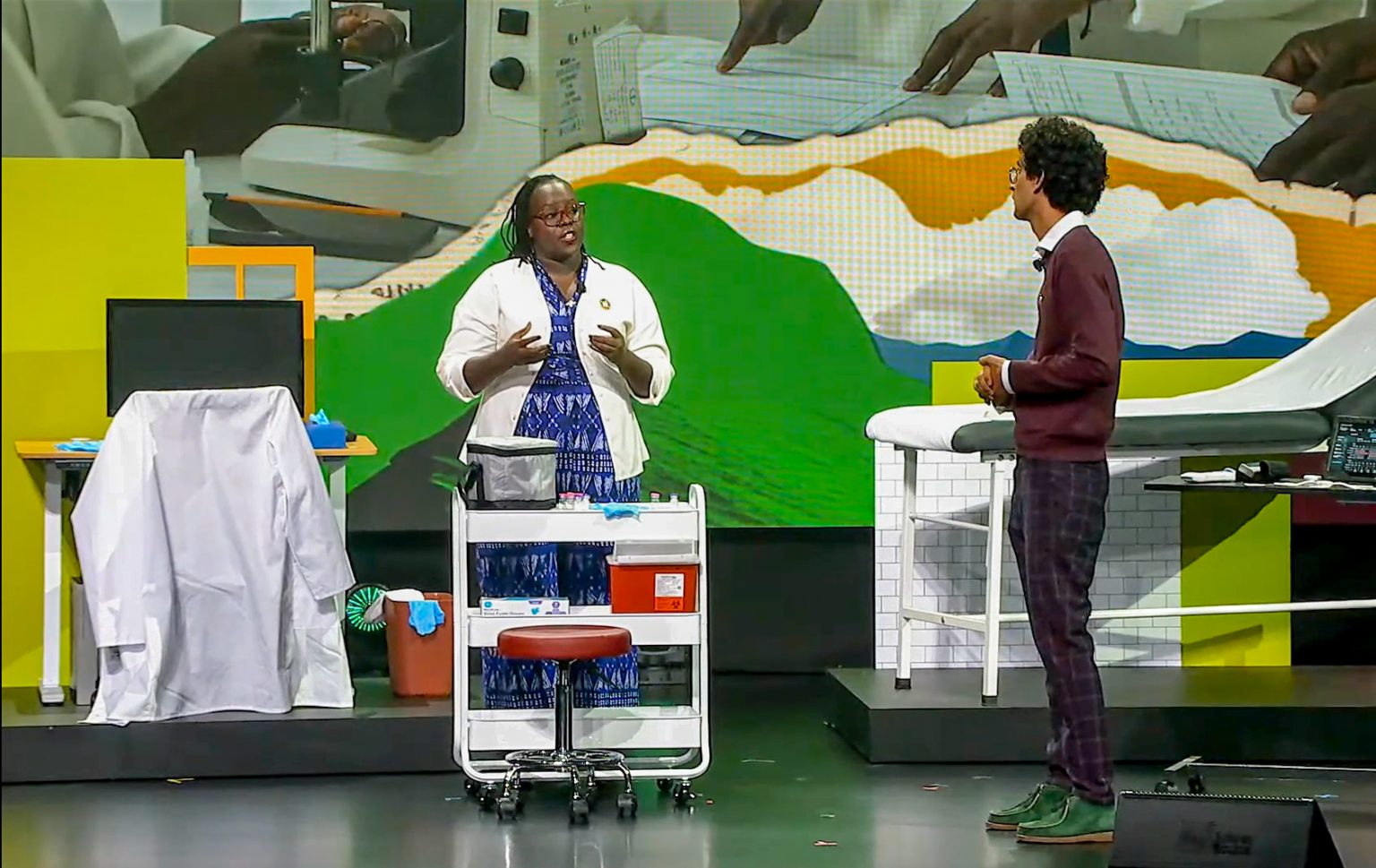

In New York City, far from the shores of Lake Victoria, where mothers struggle to keep their newborns alive, Kenyan researcher Dr Hellen Barsosio has pledged to fight maternal and infant deaths by pushing for wider access to lifesaving vaccines.

Dr Barsosio was speaking at the Goalkeepers 2025 event, which brought together global leaders, activists and innovators united by a shared desire to confront the world’s toughest challenges and give every child a fair chance at life.

Dr Barsosio’s journey researching maternal health is rooted in the story of her grandmother, a traditional healer on the shores of Lake Victoria in Kenya, where she was revered for her knowledge of herbs and healing remedies, yet woven into that legacy was a private tragedy.

“She had eight pregnancy losses,” said Dr Barsosio. “Miscarriages, stillbirths, and babies who did not live beyond their first month of life.”

The heartbreak seemed endless until she attended an antenatal clinic while pregnant with Dr Barsosio’s father. Embracing modern medicine is what saved her life. “That was the turning point,” she told delegates. “It is the reason I am here today, following in her footsteps. But where she sought new herbs, I search for new drugs and vaccines to make sure babies are born healthy and stay healthy.”

Once a pregnant woman is vaccinated, the antibodies cross her placenta to the unborn child, arming the baby with protection

She said her commitment lay in advancing maternal vaccines to give newborns a stronger chance at survival. The science, though decades old, is elegant in its simplicity. Vaccinating a pregnant woman prompts her immune system to produce antibodies.

These “tiny soldiers”, as Dr Barsosio calls them, cross the placenta to the unborn child, arming the baby with protection against deadly infections from birth. Kenya, for instance, has used maternal tetanus vaccines for 40 years with transformative results.

“I learnt about neonatal tetanus in medical school,” Dr Barsosio said. “But I have never seen a case in my practice. That’s how effective maternal vaccines can be.”

Yet vaccinating pregnant women raises questions about safety. Dr Barsosio emphasised the rigorous oversight these vaccines undergo before reaching clinics.

“They are tested in clinical trials, scrutinised by safety experts, and continuously monitored even after approval,” she explained. “If any signal raises concern, regulators step in immediately. We are sure our mothers and babies are safe.”

What excites her most is not only what vaccines have achieved, but also what lies ahead. Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), for example, is the leading cause of viral pneumonia in infants under six months and a major driver of hospital admissions worldwide. Each year, it kills an estimated 100,000 babies and leads to 1.4 million hospitalisations.

Already, a maternal RSV vaccine has been licensed and used in high-income countries for nearly two years. Until now, poorer countries have been unable to afford it. That barrier is beginning to shift.

“Gavi, the global vaccine alliance, has approved it,” Dr Barsosio announced. “Very soon, places like Sokolo Dispensary in Western Kenya will be able to offer it to pregnant women.”

In the next five to ten years, low- and middle-income countries could have access to vaccines against Group B Streptococcus bacteria

Another looming threat is Group B Streptococcus (GBS), a bacterium that silently colonises mothers during pregnancy. Though asymptomatic in adults, it can pass to newborns and cause stillbirths, deadly blood infections, and long-term neurological damage. Globally, it is linked to more than 40,000 stillbirths and 90,000 infant deaths every year.

“What I dislike most about GBS is that babies don’t even get a fighting chance,” Dr Barsosio said. “But vaccines are in late clinical development. In five to ten years, we hope they will be available even in the most remote corners of the world.”

For Dr Barsosio, the statistics are always human. Her work takes her to Sokolo Dispensary on Mfangano Island, where reaching patients takes an hour-long boat ride across Lake Victoria, followed by a precarious motorbike climb up a steep hill.

“I’ve fallen off that motorbike a few times,” she laughed, “but it’s worth it if women like Atieno in Sokolo can get the same vaccines as mothers in high-income countries.”

That vision of equal access, regardless of geography or income, is at the heart of her mission.

The theme of this year’s Goalkeepers event, “We Won’t Stop at Almost”, struck a chord with Dr Barsosio. For her, the words are not abstract; they are bound to her grandmother’s story and the countless women who continue to lose children to preventable causes.

“I think about my grandmother every day…a vivacious, vibrant woman who lost so many babies before she could even hold them,” said Dr Barsosio. “Her story is not unique. Too many mothers go through the same heartbreak. We won’t stop at almost, because every mother deserves the gift of a healthy baby who survives and thrives.”