Alicent Ruto was diagnosed with a spinal tumour – whose surgery needed Ksh300,000 in 2018. Raising the money and ensuing medication took five years almost ruining her athletic career

In the hilly town of Iten 36 kilometres from Eldoret, dreams are born with the sunrise, but not all survive to see it set.

Here, running isn’t just a sport—it’s a way out. Every day, as the sun splashes its light over the highlands, the roads come alive with the sound of pounding feet. Men and women race against time, chasing more than just medals. They run for a shot at something bigger—freedom from poverty.

For 37-year-old marathoner Alicent Ruto, running has always been more than a passion. It was her lifeline. The mother of two spent her youth sprinting to podiums, collecting medals that adorned the walls of her modest home, proof of her victories. She had run in Brazil, Morocco, the Netherlands, and countless local races.

“I was running to make money,” she says, her voice quiet but steady. “I had brothers in school, and I wanted to support their education. I also wanted to build a house back home.”

But behind those shimmering medals lies a story of endurance, not just of the body, but of the soul.

In 2018, during her preparations for a major race in Morocco, Alicent felt a sharp pain in her waist. At first, she thought it was just the usual fatigue. She pushed through, determined not to lose her momentum. “I thought a massage would fix it,” she recalls, her eyes clouding with the memory. “But the pain returned the next day, and it was worse.”

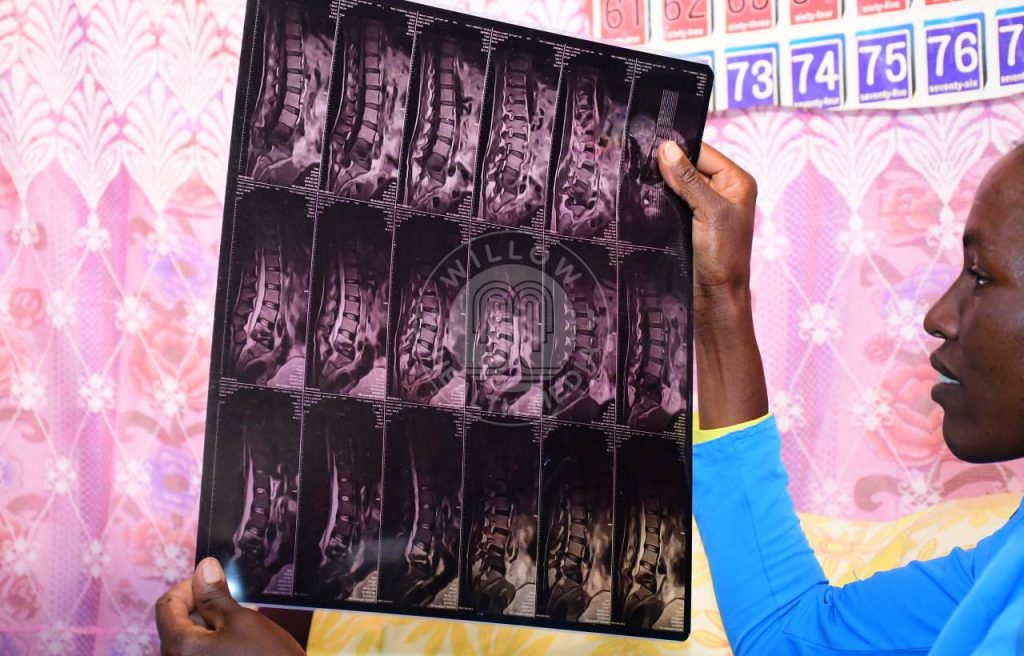

As the days passed, the pain intensified. It wasn’t just a sore muscle anymore. It felt like something was digging into her spine every time she moved. Her coach insisted she see a doctor, and after several visits and a round of tests, the diagnosis was devastating: a spinal tumour. “I didn’t know what to think,” Alicent says, her voice faltering. “The doctors told me I needed surgery, but I didn’t have the money.”

The cost of the surgery was Ksh300,000—an unattainable figure for an athlete whose income depended solely on prize money from races. “I had spent everything I had on supporting my family and trying to maintain my running career,” she explains. With no money for the surgery, she was forced to wait, and as the years dragged on, the tumour metastasised, causing more damage to her spine. “I was in so much pain that I couldn’t walk. I couldn’t even go out and meet family or friends,” Alicent recalls, her voice heavy with emotion.

It wasn’t until 2021, after two years of suffering, that Alicent was finally able to get the surgery, thanks to donations from friends and family. She spent a year on medication and was advised not to engage in strenuous activities. “By 2023, the pain had subsided, and I could only feel it when bending or walking long distances,” she says. “It was until recently that the pain fully disappeared, and I decided to start training again.”

Alicent had just returned from running 14 kilometres before the interview.

“I’m not in top form yet, but I’m happy I can run again,” she says, a flicker of hope in her eyes. For Alicent, the road to recovery has been long and painful, but she’s determined to make a comeback. “When I was sick, I thought my career was over,” she admits. “But my family gave me strength, and my faith kept me going.”

Alicent’s story is not unique. Across Iten, countless athletes battle injuries and financial struggles, with little to no support from the organizations meant to guide them. Injuries, in particular, can be a death sentence for an athlete’s career. “When you have an injury, you’re forgotten,” Alicent says bitterly. “Your coach and manager cut you off because you’re no longer showing up for practice. There’s no support system for injured athletes, and most of us can’t afford the treatment.”

For marathoners like Alicent and 34-year-old Leah Kusar, the dream of running professionally is not just about personal glory—it’s a way out of poverty. Leah, who grew up in a financially challenged household, started running to provide for her family. “I wanted to help my parents and siblings,” she says. Her talent took her around the world, from Norway to Germany, India, and Tanzania, but an injury that began in 2014 would soon derail her career.

“I started feeling pain in my right foot, and over time, it moved up my leg to my hamstrings, thigh, and hips,” Leah recalls. Despite the pain, she continued to compete, pushing through races in Finland and India. However, after taking second place in a half marathon in India in 2016, Leah’s injury became unbearable. “I couldn’t run anymore,” she says. “The pain was too much.”

Leah took a break from running, but the financial struggles persisted. Without races, she had no income, and with no money, she couldn’t afford the necessary medical treatment to heal her injury. “It got to a point where I didn’t think I would ever run again,” she says. “The pain was unbearable, and I had lost hope. What helped was the church. The pastor told me to keep praying, and that faith kept me going.”

This year, Leah is back on her feet, slowly recovering and training again. But like Alicent, her future in athletics is uncertain. Injuries and poverty are a vicious cycle for many athletes in Iten. Without proper medical care, injuries worsen, leading to long periods of inactivity and loss of income. And without income, there’s no way to afford the treatment needed to recover.

“Our biggest problem has to do with finances. You have nothing to do and that really demoralises us because you can’t even be able to get the food you need, pay rent, travel and participate in the races,” she says.

Leah’s husband, Michael Kasitit, knows this struggle all too well. A marathon runner with a personal best of 2 hours 14 minutes, Michael has been stuck at that time for years, unable to push past it due to a persistent muscle injury that attacks his thigh, back, and shoulder. “I’ve tried everything,” he says. “But the injury keeps coming back.”

During the Nairobi City Marathon in September 2024, the injury forced him to stop with just two kilometres to go, despite having completed 40 kilometres. “I felt a sharp pain in my thigh, and I just couldn’t move,” he recalls.

Michael shows a pair of old, worn-out running shoes from 2012. “I’ve been using these shoes for years,” he says. “Many athletes don’t have good shoes. There’s no way you can avoid being injured while using these shoes. This is a direct impact on someone’s body. That’s why we spend so much time trying to recover. How can you recover while using such shoes?”

He recently bought a second-hand pair of shoes from a friend. Though they’re too big for his feet, he says they’re in much better condition than the ones he had before.

Coach Benson Matheka, who has been training athletes in Iten for years, agrees that shoes are a significant factor in athletes’ injuries. “Good shoes are essential for long-distance running, but they’re expensive,” he explains. “The best shoes cost more than Sh10,000, and most athletes can’t afford them. If an athlete is wearing worn-out shoes or shoes that aren’t properly cushioned, they’re bound to get injured. It’s like running on rocks.”

And it’s not just the shoes. The poor roads in Iten, where the athletes train, contribute to the constant cycle of injuries. “These roads are terrible for us,” Coach Benson says, shaking his head. “Whenever they’re working on the roads, they just throw stones everywhere, and the athletes have to step on them while running. It’s no wonder so many of them get injured.”

“Finances are the biggest challenge for these athletes. Even with serious injuries, they can’t afford a professional physiotherapist and they settle on quacks,” adds the coach.

There are also very few local specialists in sports medicine despite Kenya being a sporting powerhouse in the world. And while Athletics Kenya, the national governing body for athletics, has signed hundreds of athletes, the number of sports doctors available is shockingly low.

For instance, there are about 10 orthopaedic surgeons in Kenya in sports-related injuries. Like Dr Paul Miano, an orthopaedic surgeon, who says the situation is dire as “cost is also a big issue because most sport-related injuries are quite expensive. Even accessing that in a public institution becomes difficult.”

Dr Miano further notes, “We work with physiotherapists, but when you have a ligament injury, you have to be in the theatre. That boils back to the number of surgeons and the cost of treatment. This makes it very difficult for most athletes and sportspersons.”

There is thus a huge gap in Kenya’s medical sports infrastructure which is strained by the fact that “in sports medicine, you have to go abroad and train, a significant challenge for those entering the profession,” says Dr Miano.

Locally, the few sports medicine practitioners charge an arm and a leg as Dr Miano estimates tendon and ligament repairs to cost between Ksh250,000 to Ksh400,000, unattainable figures for many athletes, especially those without sponsorship or adequate financial backing.

Similarly, high costs are aggravated by limited suppliers of medical equipment, which according to Dr Miano are about five “which drives the cost up making it difficult for many athletes to receive proper care.”

Yet, despite the odds, athletes remain resilient. They continue to lace up their shoes, push through the pain, and hope for a better tomorrow. “I’ve trained for 18 years. I still want to run 2 hours 8 minutes or 2 hours 9 minutes,” says Michael. “I won’t stop until I reach my target. I just pray and believe that I will run that time and retire.”

For now, the road to victory remains uncertain. But for these athletes, every step, no matter how painful, is a step toward a dream they refuse to let go of.