Prof Arthur Obel’s death ends a bold, controversial chapter marked by daring HIV/AIDS therapies that once fetched Ksh30,000 a bottle on the 1990s black market.

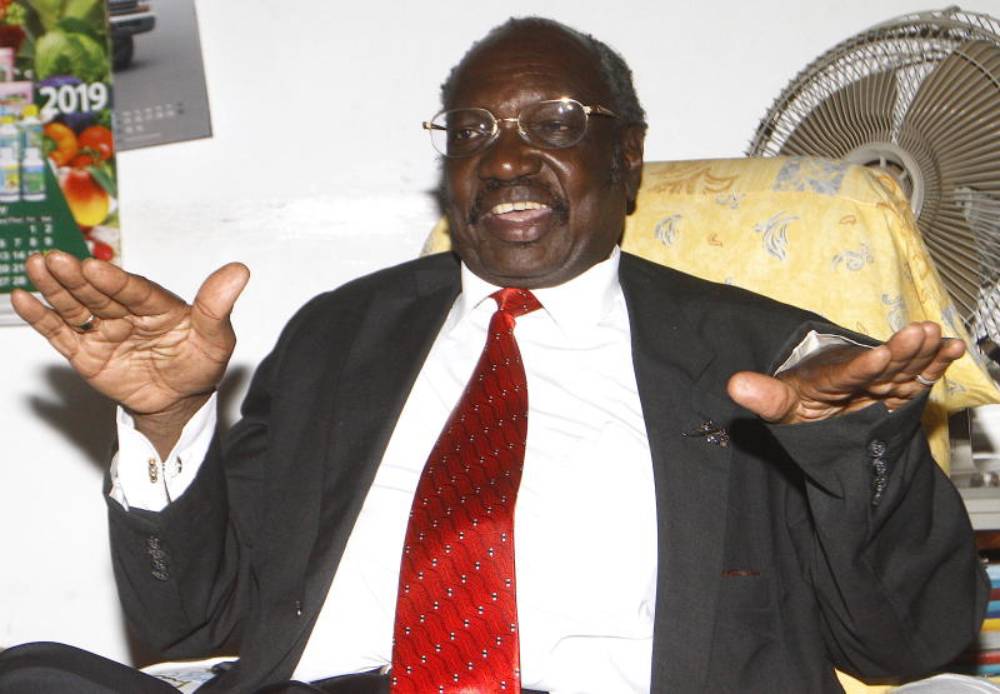

Prof Arthur Obel, a pioneering HIV researcher, gun lover and collector of Mercedes-Benzes, died on September 27, 2025, in Nairobi after a prolonged illness.

His death, at 79, closes a chapter on the life defined by medical audacity, personal controversies and unflagging zeal to confront one of Africa’s deadliest epidemics.

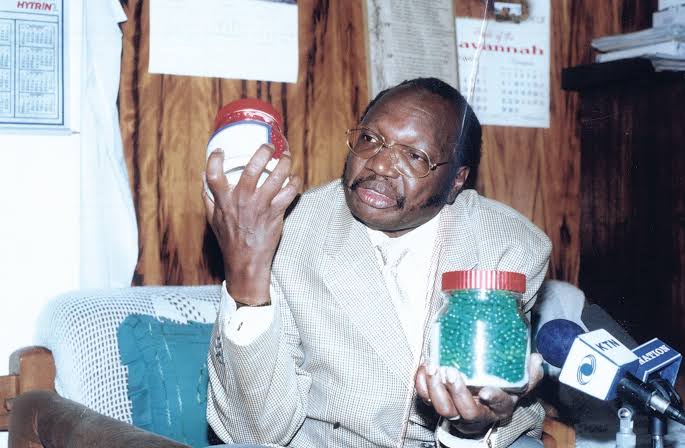

See, in the early 1990s, when HIV/AIDS was killing Kenyans in their thousands every month, Prof Obel announced the discovery of Kemron and Pearl Omega, two drugs he claimed eliminated the retrovirus, when options for a cure were scarce.

President Daniel arap Moi announced that 50 patients had been cured by Prof Obel’s drugs.

But alas! the scientific community adjudged the drugs to have little or no effect against HIV/Aids: America’s National Institutes of Health dismissed Kemron as a mere placebo, while South Africa’s University of Pretoria couldn’t find data to support the drug’s efficacy. The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared that the drugs did not meet international medical standards.

Cops arrested medics who first announced Kenya’s first HIV/Aids cases

But seeing a chance to put Kenya on the global medical map, President Moi’s government backed Prof Obel in cash and kind. Never mind police had arrested medics who first announced Kenya’s first HIV/Aids cases in 1984, fearing that the news would ‘scare tourists.’

In fact, the first Kenyan to publicly declare his positive status from ‘the sex disease’ was the late Joe Muriuki in 1987: He was sacked from his accounting job at the Nairobi City Council, his wooden seat thrown out the window.

His wife was dismissed from teaching in a public primary school, while bank tellers didn’t find a need to open an account for Muriuki since “You’re going to die anyway.”

In this, the darkest of medical hours, came Prof Obel with a local solution to a global scourge. One can safely say Prof Obel fumbled, but stumbled forward, paving the way for Kenya’s eventual coordinated response to HIV/Aids.

At a personal level, Prof Obel was not the jalopy-driving scientist in a white lab coat that may well be a veneer for hidden ambition and cut-throat go-getting.

Police found a pistol, a shotgun and 19 bullets at Prof Obel’s two Nairobi homes

Neither could he turn the other cheek when push came to shove, which is why he found himself facing a murder charge after shooting a matatu driver in July 2004.

Police would find a pistol, a shotgun and 19 bullets at his two, well-appointed Nairobi addresses.

John Kyalo, the matatu driver, had blocked Obel, who told the court he was rushing home to switch off some equipment failure of which an experiment would have gone awry, and the driver had ignored his requests to give way.

Obel later told a Nairobi court that he brandished a pistol when matatu crews formed a human wall around him, after which they dispersed as the passenger vehicle sped off. He was acquitted on the attempted murder charge but fined Sh400,000 for injuring the driver and Sh100,00 for damaging the public service vehicle.

Prof Obel lived large in science and socially. In his garages at Nairobi’s Lavington and Loresho homes would be parked a total of 11 marques. In Obel’s books, the automobile was more than a box on four wheels for moving from point A to B.

Prof Obel’s Mercedes S-320 was the first of its kind to be imported in Kenya

“I love cars. Not just any car. Only the fast and the stable,” he told Daily Nation feature writer John Koigi in 2007. They were not the sort of cars you write cheques for at a showroom and shortly drive away in them. They were custom-built German symphonies-for-motion, assiduously polished. No expense was spared to maintain the automotive pedigree. And the fuel tanks were always full.

On the interview date, the speed-loving professor had forced a Daily Nation Toyota to strain as it kept pace with his Mercedes-Benz 260 SE.

“It took four years to customise the BMW 728i in Bavaria,” the reporter heard about one of the cars. It boasted a legal blue interior, pricey curtains, a retractable GSM phone and cruise control. Shall we say the make and the state of a car describe its owner?

The Mercedes S-320 was the first of its kind to be imported in Kenya, reported the paper.

Prof Obel earned a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery and an MD in Clinical Medicine from the University of Nairobi en route to a PhD in Therapeutics from London University in 1978.

But his fame and infamy rested on developing Kemron and Pearl Omega, which were later established not as effective against the retrovirus, as they only provided a fleeting relief.

The Health Minister Joshua dismissed Pearl Omega as an herbal concoction

Initially, Health Assistant Minister Basil Criticos spoke of the government’s readiness to finance the clinical trials of the drug. Later, in the wake of a backlash from scientists and patients, health minister Joshua Angatia dismissed Pearl Omega as an herbal concoction whose efficacy had never been tested.

Other quarters accused Obel of lowering the concentration of medication that had been denied approval for testing in the US, and chest-thumping that he had found the cure for HIV/AIDS.

In 1989, the professor joined the Kenya Medical Research Institute, KEMRI, as the Chief Research Officer. There, he developed the drugs in close collaboration with the institute’s boss, the late Dr Davy Koech, who was President Daniel Arap Moi’s protégé, thus guaranteeing considerable government support for Prof Obel’s projects.

Former University of Nairobi Vice Chancellor Prof Philip Mbithi, Obel’s friend, was the Head of the Civil Service and the Chief Secretary in the Office of the President, meaning Prof Obel had his ducks in a row. Obel would later be named the Chief Scientist in the powerful Office of the President.

Prof Obel stuck to his guns, popularising his drugs in defiance of the Ministry of Health

In 1993, Obel launched Kemron, claiming it was clearing symptoms of HIV/AIDS in patients, attracting national and international attention. Condemnation was in larger doses than appreciation.

Not to be pulled down by dismissive scientific opinion, Obel stuck to his guns, popularising his drugs in defiance of the Ministry of Health.

He would continue with his therapies with Pearl Omega and Kemron, going for Ksh30,000 a bottle in the black market, a tidy sum in the early 1990s, as he claimed he had healed seven HIV/AIDS patients. He didn’t provide scientific evidence to back his claim.

At his offices in downtown Nairobi, desperate patients would wait for Obel, hoping to get a bottle of his drugs, but he couldn’t cope with the demand.

Patients who felt exposed to untested drugs dragged him to court

Obel would be sued by the Kenya AIDS Society in 1998 for manufacturing and distributing Pearl Omega without the approval of the Ministry of Health, but he won the case in 2019.

Patients who felt they had been exposed to untested drugs also dragged him to court, but he was not about to stop his enterprise.

Barbara Justice, a New York Physician at Abundant Life Clinic, claimed that 82 per cent of their patients had increased appetites after using Kemron.

A restless bolt of energy, Prof Obel wrote Curbing the HIV/AIDs Menace Effectively, besides other works on anti-biotic therapy, the use of insulin and treatment of gout.

He is the author of Power and Intrigue, Kenya’s Industrialisation Strategy, Resilient Manhood and Dynamism and The Basis of Rapid Takeoff.

As he was wont to, Prof Obel was a member of The Global Epidemiology Society, Achievers Society, fellow of the Jewish Federation, Diabetes Federation and the Global Pharmaceutical Federation.

Wambua Sammy is a Consulting Editor.