Despite a Ksh700 billion education budget, Kenya’s public schools lack nurses, proper first aid, and trained staff, leaving thousands vulnerable to medical emergencies.

In Nairobi’s public schools, the vibrant energy and chatter of learners mask a hidden crisis that puts thousands of young lives at risk every day. Consider this: despite a Ksh700 billion education budget, no direct funding was allocated toward school-based healthcare: no standalone provision for clinics, primary healthcare services, nurses or counsellor staffing and mental health support.

Kenya’s public schools thus lack access to basic healthcare services, leaving thousands vulnerable to medical emergencies. To worsen matters, schools have no trained nurses on site, leaving teachers to make critical health decisions without medical training.

A spot check of several public primary schools in Nairobi by Willow Health Media revealed a healthcare plan “often left entirely to chance.” Most schools rely on informal arrangements with nearby clinics where children are rushed out the gate during emergencies.

Other times, the only option is to call a parent or guardian, with teachers or administrators expected to make medical decisions on the spot, without basic training in first aid or health protocols. It is a system held together by goodwill and improvisation.

Mildred Achieng, a parent with children at Olympic Primary school in Kibra, says when a child falls ill, “They don’t do anything, they just call the parent to come pick them up and take them to the hospital.”

Mildred recalls being called in March when her child developed a fever, as “no first aid was given at all.” According to Mildred, there is no sickbay for the children and no health professional or nurse available.

Child left home in good health but developed a fever, had a runny nose, and was coughing

Anthony Onyango, another parent at Olympic Primary school, also recalls being called when his child “left home in good health but developed fever, had a runny nose, and was coughing.”

In Kenya, common health problems in schools include mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression and conduct problems, communicable diseases like malaria, diarrhoea, tuberculosis and pneumonia, alongside emerging non-communicable diseases like cardiovascular diseases, cancer and diabetes.

A 2022 report by APHRC indicated that 12.2 per cent of adolescents experienced a mental disorder, with anxiety being the most common.

Mildred, a Community Health Promoter (CHP), says her child often suffers from diarrhoea while at school. “He often comes home with it, and I tell him it’s because the school environment is not clean.”

Onyango, on the other hand, also concurs, “Some illnesses like flu and other contagious diseases are contracted while children are at school.”

Education expert Johnstone Shisanya says, “Healthcare in schools is not a privilege, it is a right,” but most times, parents and guardians are informed after a child has been attended to or rushed to the hospital during emergencies.

The defunct National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) had Edu Afya, but it only covered high school students -whose health was the responsibility of school management and government.

NHIF was replaced with the Social Health Authority (SHA) in October 2024, and Shisanya explains that, in it, students are supposed to be provided with medication even “if it is first aid before the parent comes.”

The Ministry of Education had urged parents and guardians to ensure their school-going children are registered before February 28, 2025. To assist in the rollout, Community Health Promoters (CHPs) were deployed to schools to reach the target of registering over 15 million learners by the end of the term in April.

Children not registered in SHA, have not paid up, are turned away in government health facilities

By the time this order was given in mid-January, over 17 million Kenyans had been registered to SHA. Latest figures as of May 2025 show that over 23 million Kenyans have been registered. Of these, the number of dependents under 18 years is 6,327,214 (68.6 per cent).

Information from the Ministry of Health shows that SHA covers all primary and secondary school children, granting them access to the full range of benefits under their parents’ or guardians’ benefits package. This marks a shift from the previous EduAfya programme, which only covered students in public secondary schools.

However, Prof Samson Gunga, Professor of Philosophy of Education at the University of Nairobi, notes that children who are not registered in SHA and have not paid up are often turned away in government health facilities.

This, he argues, directly violates the child’s constitutional right to the highest attainable standard of health, both at school and at home, contrary to the Constitution of Kenya (2010) and the Children Act (2022).

Indeed, the Basic Education Act (2013) empowers the Ministry of Education to integrate health programs and essential support services into the education system.

The National School Health Policy (2018), developed jointly by the Ministries of Health and Education, addresses eight crucial areas:

- Nutrition

- Disease prevention and control

- Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH)

- Mental health

- HIV & AIDS prevention

- Sexual and reproductive health

- Special needs and disabilities

- School infrastructure and environment

Registered schools should have a designated space for handling minor medical issues

These aren’t mere guidelines but legal obligations whose implementation in public schools remains weak and fragmented.

“The shortage of funds from the government really is the main issue,” says Prof Gunga. “And even if it has funds, it does not remit to schools in time and does not even remit the adequate amount required.”

Good policies exist, but without enough money, they fail.

According to the National School Health Policy (2018) and Basic Education Act (2013), each registered school is required to have:

- A designated space for handling minor medical issues

- Stocked first-aid or health kits

- Trained personnel, such as a nurse or mental health counsellor

According to Shisanya, when it comes to the Ministry of Education, quality assurance plays a critical role, especially during the registration of schools and institutions.

“So, when the quality assurance does the assessment, public health comes in, it’s part of the assessment,” adds Shisanya. “They are supposed to come into the school to inspect the public health facilities, including wash facilities. Do you have water? Is the water safe for drinking? Do you have latrines? Are they placed in the right location? For example, maybe you’ve placed the pit latrines or toilets next to the kitchen—what are the health hazards of that?”

“All these issues of safety and health are addressed by the public health department,” he explained.

School nurse administered anti-malarial medication without confirming the diagnosis

But in reality, these provisions often remain just tick-box exercises on registration forms. “The government sends the quality assurance people,” says Prof Gunga. “They send very good reports to the office. So, on paper, the schools are okay. On the ground, there is nothing.”

Medical negligence in schools has seen families seeking justice in court.

For instance, Gilgil Hills Academy, a private boarding school, was sued in 2009 after a student deteriorated and died under school medical care when a school nurse administered anti-malarial medication without confirming the diagnosis or escalating to qualified personnel. The court found a breach of the duty of care owed by the school and held the institution liable for negligence in healthcare provision.

In another lawsuit, parents sued Registered Trustees of Loreto Sisters Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary after their daughter sustained severe spinal injuries after diving into a school swimming pool during practice at Loreto Msongari, leading to permanent paralysis in 2006.

The plaintiffs alleged negligence, vicarious liability, and breach of contract against the school and sought general damages for pain, suffering, and loss of amenities, damages for lost prospects of marriage and diminished future earnings capacity. They also sought relief for future medical and nursing care costs, including physiotherapy and related accessories and services; Special Damages of Ksh32.9 million. In 2024, the High Court found the school had neglected its duty of care and had a case to answer.

Also in 2024, the HIV and AIDS Tribunal ordered compensation of Ksh650,000 to the family of a Grade Two pupil expelled and discriminated against due to HIV status at Najah Primary School, Garissa. His mother had discreetly managed his medication with help from his older brother at the same school. This case highlights a critical failure in healthcare accommodation and non-discriminatory practices within schools, showing how stigma can directly harm a student’s well-being and right to education.

Record Budget, Missing Healthcare

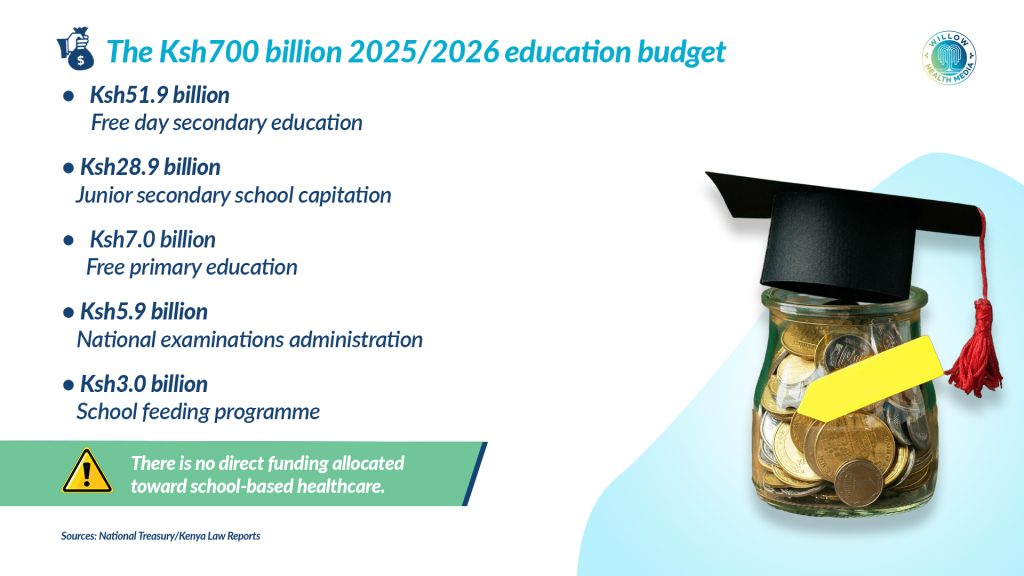

In June 2025, Treasury Cabinet Secretary John Mbadi presented Kenya’s 2025/2026 national budget with a historic allocation of Ksh702.7 billion to education, accounting for 16.6 per cent of the total Ksh4.29 trillion budget.

Breakdown of the 2025/2026 Education Budget:

- Ksh51.9 billion – Free Day Secondary Education

- Ksh28.9 billion – Junior Secondary School Capitation

- Ksh7.0 billion – Free Primary Education

- Ksh5.9 billion – National Examinations Administration

- Ksh3.0 billion – School Feeding Programme

While the School Feeding Programme contributes to learner nutrition, an essential component of child health, no direct funding was allocated toward school-based healthcare. Yet these services are not luxuries; they are legal and policy requirements.

Onyango argues that healthcare in schools is “a challenge and the government should consider setting up a health clinic within the school, especially because the children (at Olympic Primary) are so many” and the bare minimum should start with the provision of first aid.

Child psychologist Lewis Karanja says many institutions have “limited child psychologists in schools,” yet their presence is essential in addressing students’ individual emotional and psychological needs, as “Every child’s need is unique”, and as professionals, they understand children’s psychological needs more deeply.

Some countries have managed to implement school healthcare systems that are beneficial to school-going children.

Like the South African Integrated School Health Policy (ISHP), a government initiative launched in 2012 to provide comprehensive and integrated health services, including health education, screening, and onsite interventions.

It covers health screening, immunisation, sexual and reproductive health education, and psychosocial support. Teams (nurses, social workers, oral hygienists) visit schools, particularly in underserved areas.

In Sweden, every school has access to a school health team: a nurse, doctor, psychologist, and counsellor. The focus is nutrition, physical activity, mental well-being, and regular check-ups – fully funded by public health.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has for many years emphasised that health and education are connected, and that schools can play a key role in protecting students’ health and overall well-being. In 1995, the Global School Health Initiative started to improve how schools promote health, with one of the main strategies being to link children directly to health services.