In 2006, Kenyans with all manner of illnesses including HIV, went to a remote village in Tanzania for a cup of herbal concoction from ‘Babu wa Loliondo.’

Peter Mukoshi Lumumba grew up in a community where misfortune was rarely seen as random. Instead, it was believed to be the work of those who harboured ill will, those envious of one’s progress.

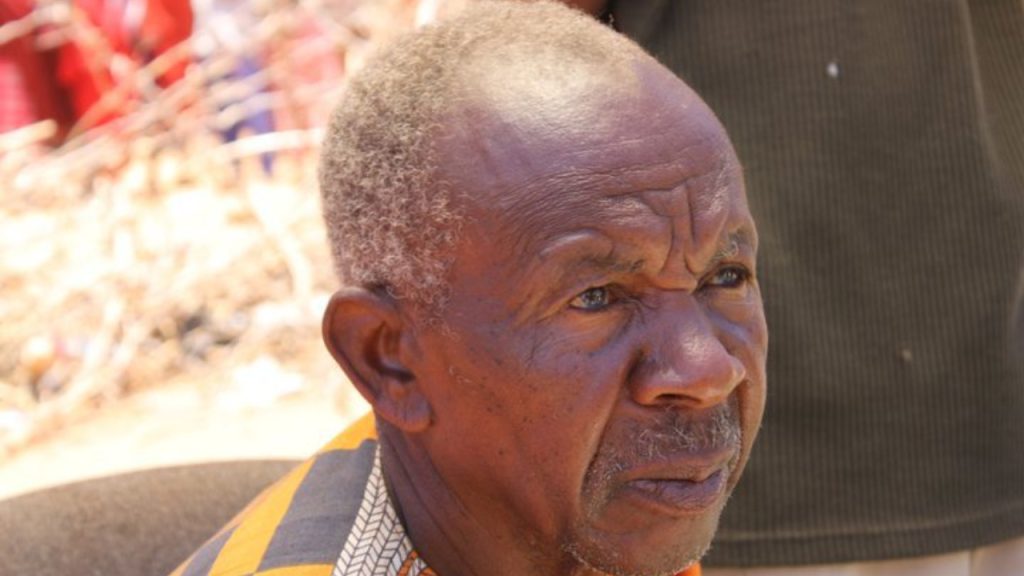

So, when the man from Lwesero in Lurambi constituency, Kakamega County began experiencing persistent joint pain, headaches, coughs, and a noticeable darkening of his skin, he did what many did at the time—he sought help from a traditional healer- who attributed his troubles to malicious relatives.

The prescribed traditional herbs brought brief relief, but the headaches and coughing were relentless. A visit to the hospital in 1987 brought clarity: it was HIV/AIDS. Not wanting to transmit the virus to his wife, Beatrice and future children, he underwent a vasectomy besides adhering to traditional and conventional medicine in treating opportunistic illnesses.

Breakthrough came with antiretroviral therapy (ART) around 2003, but a chance pep talk with Otieno, a colleague in the matatu industry would change all that.

Otieno told him about a miraculous cure in a village called Samunge in Loliondo near Ngorongoro, northern Tanzania.

“He spoke convincingly how people were healed from HIV/AIDS for just Ksh36,000,” recalls the now 61-year-old father of three HIV-negative children, one now deceased. “We had already spent a lot trying to manage the virus with limited success. Looking into his eyes, I saw that he was serious. I scraped some money, and we travelled to Loliondo.”

Loliondo was famous for ‘Kikombe cha Babu’ (Grandpa’s Cup), a concoction of non-flavoured herbal remedy from the mgaringa tree created by Ambilikile Mwasapile, a Tanzanian Lutheran priest and herbalist known as ‘Babu wa Loliondo.’ He was then not famous. The crowds seeking treatment were smaller.

But unable to meet Babu, Lumumba paid for ‘Kikombe cha Babu’ from ushers with the assurance that faith in the potion was essential for it to work.

Indeed, the hope of healing, faith and spirituality, distrust in modern medicine, affordability, and word of mouth drove the pilgrims to Loliondo.

Hopeful of healing, Lumumba stopped his ART, but alas! his health failed to improve. Otieno’s health too, was visibly deteriorating.

The Brothers-in-Arms decided to make a second trip to Loliondo five years later, when Babu’s fame saw tens of thousands of patients from Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, DRC, Malawi, Zambia, Ethiopia, South Africa and Sudan seek treatment for HIV, cancer, hypertension, chronic pain, infertility, asthma, TB, arthritis and diabetes.

Most endured through impassable terrain to Babu’s homestead as he could not administer the concoction elsewhere: God revealed it would lose its efficacy, he told the Daily Nation. Lumumba set aside all doubts, promising himself two things: he would meet Babu and take the concoction with unwavering faith to cure HIV/AIDS.

Babu claimed the concoction took seven days to cure other ailments, but three to four weeks was necessary for the HIV to clear, allowing one to test negative.

Dr Richard Ole Nkapi, a Tanzanian doctor who investigated Babu’s wonder cure, said it was chiefly made from the Mgaringa plant (Antiaris toxicaria), or poison arrow root. Surprisingly, Dr Nkapi had claimed ‘Kikombe cha Babu’ had “cured” his diabetes. But Dr Julius Mbuyu, another Tanzanian doctor, said conditions did not change for HIV-positive and diabetic patients who visited Babu.

Lumumba too returned home where his condition worsened: he developed a form of skin cancer that left his legs ulcerated and foul-smelling. Accepting his fate, he began to prepare for the end.

The lack of scientific credibility on Babu’s cure saw the Loliondo pilgrimage dwindle. Old age caught up with Babu, while the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic restricted large gatherings, waning Loliondo’s appeal alongside diminishing media hype, which drove the initial interest.

It was at this low point that Robert Amakobe, a dedicated HIV/AIDS home-based care specialist associated with AMREF, came knocking.

“Lumumba’s family were preparing for his final days,” says Amakobe. “A colleague and I started by encouraging him to resume conventional treatment, which he had abandoned because he felt ART was burdensome and couldn’t cure HIV/AIDS. We also tended to his infected wounds and coordinated his medication. This was around 2008-2009, just after he returned from Loliondo.”

Lumumba’s friend Otieno, died in 2011.

Amakobe says Tanzania is known for its Traditional Complementary and Alternative Medicine (TCAM) and many Kenyans went there after failing to get solutions from Kenyan traditional healers regarding HIV/AIDS symptoms like persistent fatigue and opportunistic infections such as skin conditions and gastrointestinal issues.

Just like Lumumba, Doreen Moraa Moracha, went to Babu wa Loliondo hoping for a miracle cure for HIV.

“It felt like a lifeline,” she recalls. “Babu was not just selling medicine; he was selling hope, and we were buying it. He spoke with such confidence. My mum and I, desperate for any solution, decided to make the journey.”

There were hundreds of people, says Moracha and “the process was simple: pay Ksh100, receive a cup of brown liquid, and believe that we’d been cured. There was no question of how it worked; there was only faith.”

But reality shortly set in. Doreen’s mum went for a test after three months, only to find HIV was still there. Doreen on the other hand, stubbornly stopped taking ARVs, believing Babu’s herbal cup would work.

“A year later, tests showed that my viral load was rising. I still refused to go back to the hospital, until one night, I woke up with a fever and severe swelling in my mouth. My mum rushed me to the hospital, where I was diagnosed with an opportunistic infection,” she added.

The doctors explained that her viral load was dangerously high, putting her at risk of AIDS. They gave her antibiotics to treat the infection, but the harsh truth was clear, she had to return to her ARVs without shortcuts.

TCAM treatments, rooted in cultural practices, are widely used and recently, the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) has been exploring how best to integrate herbal remedies into HIV/AIDS management.

A notable example is a clinical trial on the Canova Immunomodulator, a herbal formula containing elements like Aconitum napellus, Bryonia alba, Thuja occidentalis, and the venom of Lachesis muta.

Approved by the Kenyatta National Hospital Ethics and Research Board in 2009, the trial sought to evaluate the product’s safety and efficacy in reducing viral loads and strengthening immunity. While the results remain uncelebrated, KEMRI insists on the importance of local trials to validate such remedies.

Additionally, an ethnobotanical survey in Kisii County documented nine medicinal plants like Aloe vera, Prunus africana, and Azadirachta indica traditionally used by herbalists to manage HIV/AIDS. The survey involved 15 herbalists, whose expertise stemmed from familial apprenticeship, formal training, or self-acquired knowledge. Notably, two participants held doctorates in medicinal herbology and biochemistry. The researchers pointed out the need for clinical trials to substantiate these remedies’ efficacy and safety as they could be of “fundamental importance”.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that around 80 per cent of people in developing countries rely on traditional medicine to address various health conditions. This preference is driven by factors like accessibility, cost-effectiveness and indigenous knowledge used for centuries to maintain health.

But what continues to drive preference for herbal remedies in treating or managing conditions as complex as HIV/AIDS in modern times?

A 2020 study, Traditional, Complementary, and Alternative Medical Cures for HIV: Rationale and Implications for HIV Cure Research, explored three reasons.

Firstly, access to ART can be limited, particularly for those living in remote or underserved regions. Secondly, as was the case with Lumumba, cultural and social factors significantly influence beliefs about TCAM as traditional medicine frequently overlaps with spiritual and religious practices. Lastly, individual beliefs and personal preferences also play a crucial role, are traditional remedies safer?

In Tanzania, a study released in June titled Herbal Medicines Use Among HIV/AIDS Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy and Its Influence on Viral Suppression and CD4 Count, examined the impact of using herbal medicines alongside antiretroviral therapy (ART).

The survey involved 375 people living with HIV (PLHIV) with an average age of 39 years: No significant difference was observed in viral load reduction or CD4+ count improvement between those using both ART and herbal medicines and those relying solely on ART. In fact, patients who exclusively used ART had slightly better odds of achieving viral suppression compared to those who combined ART with herbal remedies.

The study also noted that the use of herbal medicines was often associated with additional chronic conditions like diabetes, peptic ulcers, and hypertension, suggesting that these patients might be seeking extra relief for multiple health issues.

Nevertheless, the findings indicate that herbal treatments may offer little added benefit in the context of HIV management.

Of his visit to Babu wa Loliondo, Lumumba, reflects sombrely: “I don’t think it was helpful at all. I saw people collapse in the queue, dying as they waited for the concoction. Some were even buried after taking the medication.”

Dr Charo Sande, a Kenyan general practitioner, emphasizes the need for a robust national strategy to promote awareness of antiretroviral therapy (ART) while being sensitive to cultural beliefs. He advocates educating communities about ART’s proven effectiveness and the dangers of abandoning it for unverified herbal remedies, which he sees as essential for addressing the psychological and cultural factors keeping people reliant on traditional cures.

“Education campaigns can have a profound impact, particularly when they highlight success stories of individuals who transitioned from herbal remedies back to ART and are now thriving,” he notes.

Dr Sande also suggests that the government could enforce stricter regulations on traditional healers claiming to cure HIV/AIDS. However, he adds, “Instead of relying solely on enforcement, collaboration with traditional healers could be more effective. By working together, they can encourage people living with HIV to seek medical treatment, reaffirming that, as of now, there is no cure for HIV/AIDS.”

Additional reporting by Yvonne Kawira.