‘Motivated by the love of Christ… the Church is the only institution in Kenya with the capacity to forego profits for the sake of making universal healthcare accessible to as many Kenyans as possible’– The former IEBC Selection Panel Chair, Dr Nelson Makanda

In March 2016, Margaret Otiende of Maili Nne, Eldoret, started feeling weak and struggled with her cleaning job. At Huruma Sub-County Hospital, doctors diagnosed diabetes and high blood pressure.

“I was put under treatment, but my legs swelled and became painful. Sometimes I would collapse only to wake up at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital,” Otiende said, joking about how the complicated machines scared her.

Regular clinics drained her finances as she couldn’t work anymore. Her health deteriorated as money ran out. Some days she couldn’t afford the Ksh100 bus fare to the public hospital where doctors scolded her for being late “without caring I was broke and could not pay fare, buy all the prescribed medicine and adhere to a proper diet.” ”

By 2020, her feet had swollen so badly she could barely leave home. That was when a neighbour told her about the Integrated Vision Centre Church (IVC) free medical camp where “doctors assessed me, changed my drugs, prescribed insulin, and I gradually began improving,” she recalled.

In 2021, IVC opened IVC Milimani Mission Hospital, which affordably offered care as medics “cancelled the expensive drugs and gave me insulin. After several checkups, I got back on my feet,” Otiende said.

Maureen Wanjiru Madegwa, the administrator, told Willow Health Media they began as an outpatient clinic and are now working toward level four status to address the healthcare needs of the vulnerable, including widows and orphans.

The 50-bed facility provides laboratory, pharmaceutical, physiotherapy, maternal, obstetrics and gynaecology, theater, surgical, and pediatric services to Eldoret residents.

“We not only cater for spiritual needs but extend to other core needs like access to quality healthcare,” Wanjiru added.

The hospital has a modern maternity wing, the Makena Marangu Memorial Maternity Centre, honouring named the late renowned Kenyan-born, US-based doctor who helped African children access healthcare. The initiative was led by Eng. Craig Hacche, her hubby, said Joe Pecoraro, co-founder of Hearts Afire, the Christian humanitarian outfit instrumental in realizing the entire IVC hospital project.

“We are building a living legacy in her home country to serve the people she loved so much,” Hacche said.

Grace, an Eldoret patient, arrived with Ksh1,500 to give birth, but will pay the Ksh10,000 in instalments “not because I want to clear the debt but to honour the love I was shown,” she told Hearts Afire.

The maternity centre offers postpartum support, lactation consultations, childbirth education classes, and emotional counseling—services largely missing in private and public facilities.

“Our main call is to give quality care and to complement rather than compete with private and public facilities. In pursuit of UHC, there is a place for every level of hospital,” explained Wanjiru. “If we work together as a health system, we will give better services to more Kenyans.”

Dr David Wasike, Medical Officer in Charge, credits their growth to patient-centred blended with spiritual principles of love, compassion and service, including waiving some treatment fees so that patients “don’t walk away without a proper diagnosis because of lack of money.”

The Muslim community in Maili Nne comprises over 60 daily patients, as “Healthcare has no boundaries, and everyone should access it irrespective of their religion,” says Joshua Omoke, assistant administrator.

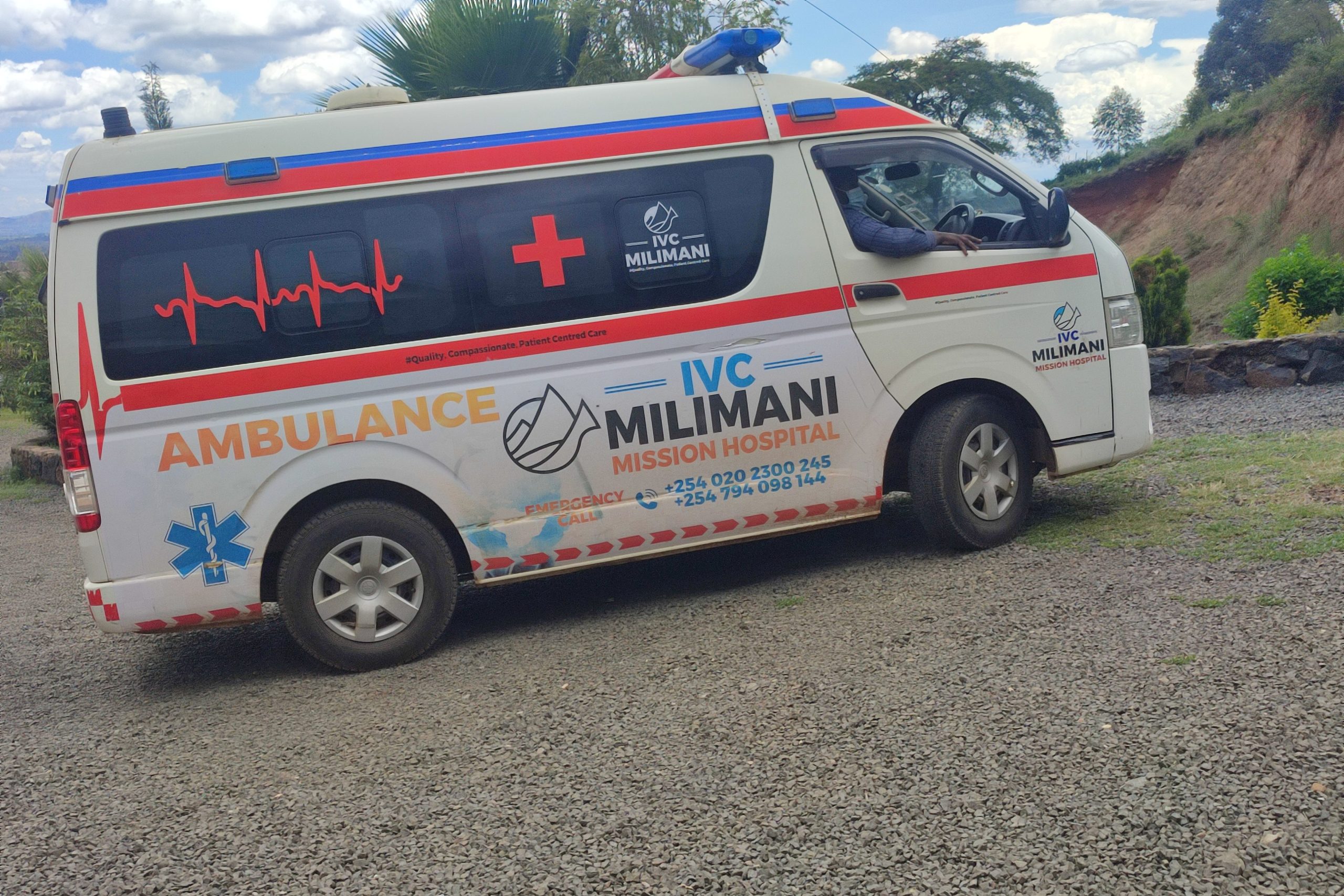

Residents within three kilometres get free ambulance services.

“Working under the Christian Health Association, which co-regulates mission facilities and partners with the Mission for Essential Drugs Supply (MEDS), has enabled us to offer quality care at affordable prices,” Omoke disclosed.

MEDS supplies reliable, high-quality, and affordable medicines, enabling mission hospitals to provide cheaper treatment. Fast patient processing reduces queues, and pre-arranged referrals ensure timely care, preventing delays common in public facilities.

Stephen Ogaye Mulehi, an artist, said that Asian, Muslim, Anglican, and Catholic health facilities also succeed due to strong governance and accountability. While private clinics are costly, government hospitals are affordable but often understaffed. Faith-based hospitals, on the other hand, have readily available doctors besides regularly host foreign medics without overcharging.

He recalls: “I once had a dental issue and went to St Francis of Assisi Mission Hospital in Mlolongo. I paid Ksh700 for a procedure that would have cost me Ksh3,000 in a private hospital.”

Eunice Nakhumicha from Busia County was admitted to St Brigittas Catholic Hospital in Yamumbi, Uasin Gishu County. She couldn’t bring a caregiver due to distance and costs, but “the care I got was beyond treatment, and that’s what warmed my heart.”

The doctors, ‘sisters’, and workers “have a good heart,” she said. “They visited patients regularly and encouraged us. Also, food and drugs came on time, unlike in public facilities where there are many people.”

Besides treatment, a priest and catechists prayed and encouraged patients, “and we felt very loved and comfortable. I think missionary hospitals are more about a calling rather than work,” she added.

Sr Rosebellah Kendagor, St Brigittas’ administrator of the 50-bed hospital, told Willow Health that the facility was established in 2000 to serve those who couldn’t access public hospitals or afford private ones.

“Our charges are affordable because it is more about care than profits. We cater for the spiritual component. The ministry of healing by Christ is what we continue with. Apart from the medicine and scientific way of treating clients, we address their spiritual needs, which is key to physical healing,” explained Sr Kendagor.

She observed that relying solely on government healthcare would deny many people access to quality services. Public facilities are overcrowded, unable to serve everyone, while private clinics only cater to those who can pay high fees.

“We are filling that gap,” says Sr Kendagor, “helping and complementing the government to provide healthcare services” including immunisation for diseases like TB and testing, counselling and managing HIV patients.

But lack of capacity to handle special cases limits the efficiency of Mission hospitals, which Sister Kendagor attributes to delayed or missing payments for services.

“We hope to elevate and become a level 5 facility and help ease pressure from Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH.),” says Sr Kendagor who has overseen St Brigittas grow from level 2 to level 4 since 2021, boasting two operating theatres, inpatient and outpatient services, optical and dental units, mother and child clinics and maternity.

“We are utilizing consultants from MTRH. We see between 40 and 70 outpatients. If SHA paid us, we could have put up extension wards,” Sr Kendagor added.

In March, the Christian Health Providers Association of Kenya (CHAK) noted only 500 out of over 1500 facilities had been empanelled on SHA-whose delayed payment were disrupting services. But by May, SHA had disbursed over Ksh5 billion, as promised by President William Ruto.

“If SHA could adhere to the contract timelines of payment within 60 or 90 days, our services would be smoother,” she explained.

Dr Philip Chebunet, a policy analyst, argues that “mission hospitals cover funding gaps in Kenya’s healthcare sector as most are well-resourced all round, and their models should be benchmarked,” Chebunet said, adding that some like Tenwek in Bomet, St Clare Kaplong, and AIC Kapsowar have specialists and expatriates who come to Kenya for unique cases.

“The unique values and guidance offered by chaplains in those hospitals to both patients and workers make the mission hospitals indispensable to Kenya’s healthcare system,” Chebunet said.

The Catholic Archdiocese of Nairobi- which has 62 health facilities under it- estimates that church health facilities provide 21 percent of Kenya’s health services. And the National Council of Churches of Kenya (NCCK) added more when its Treasurer, Kibuga Kariithi took his wife to India for stage four lung cancer treatment about a decade ago. He was struck by the high-quality, patient-centred care at a third of Kenya’s cost. This sparked the vision for Jumuia Hospitals, which he now chairs. NCCK then brought in consultants to adapt the model to Kenya’s healthcare needs.

Canon Peter Karanja, former NCCK head, said the vision needed a private, socially driven entity—focused on service over profit—as most Kenyans struggled to access affordable, quality care.

Former IEBC Selection Panel Chair, Dr Nelson Makanda, then NCCK deputy secretary, said:

“Motivated by the love of Christ… the Church is the only institution in Kenya with the capacity to forego profits for the sake of making universal healthcare accessible to as many Kenyans as possible.”

This inspired the launch of Jumuia OPD clinic in Kakamega (2014), 100-bed Jumuia Friends Hospital in Kaimosi (2015), a 175-bed Jumuia Huruma Hospital (2016), and two top-tier facilities in Embu and Limuru.

NCCK invested Ksh5 billion in phase one of a 20-year plan to build a network of affordable, quality hospitals, supported in part by a Ksh350 million loan from the East Africa Development Bank. The goal? To trailblaze Kenya’s healthcare system with 200-plus bed facilities and a super-speciality teaching hospital in Limuru.

These efforts, along with Coptic Hospital (1998) and other mission-led initiatives, underline the role of faith-based hospitals in expanding quality care, especially for the poor. Most are SHA-accredited, accepting multiple insurance plans.

Wanjiru noted that top mission hospitals like Tenwek and Kijabe prioritise service over profit:

“Doctors from abroad and mission universities often serve freely, driven by purpose—making care both excellent and affordable.”

Very true , Mission hospitals have really helped many, they play a major role in the health sector. We need more of such and the government should think of giving them opportunities to manage their facilities

True they deserve more support.

Very Insightful!

Mission hospitals need more appreciation

This is a good coverage and an eye opener for those who solely rely on public hospitals. Faith-based institutions grounded in the faith are truly the best-thier management, services, topnotch. I think many NGOs should focus on partnering with churches to establish more of these facilities . I have picked a thing. Be blessed for the information 🙏

Great read..

Great read.. Gives a good understanding of how important they are to communities.