Former Migori Governor Okoth Obado embezzled Ksh428.6 million, which could have financed essential drugs, beds, extra medics and connected power to dozens of non-functional health facilities serving over one million residents.

When Rosemary Adhiambo’s niece went into labour one evening, she was ferried by boda boda with only a flashlight for guidance to Otati Health Centre in Migori County. The facility, accessible by a treacherous road, has no piped water or electricity.

The mother from Odikeyu village delivered before midnight, but “The dispensary has no lights, lamented Adhiambo, a mother of three. One has to come with their own flashlight. There is no bed space, so patients who spend the night are mixed up with men, children and even new mothers.”

Then there is the case of an 18-year-old from Kehancha town in Migori who went into labour and was taken to Kehancha Sub-County Hospital by her sister in August 2025. Her water had broken. She was, however, treated for a Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) and sent back home. Mbusiro*(not her real name), the girl’s mother, who was following her progress on the phone, told Willow Health Media that the labour pains continued at home, forcing the family to return her to the hospital at midnight.

The daughter bled excessively during delivery. She also lost her baby. Medics said the hospital had no blood. But if Mbusiro fueled the hospital’s ambulance, the blood could be fetched 15 kilometres away in Sirare and Migori towns. Despite fueling the ambulance and donating blood, her daughter never left the theatre alive.

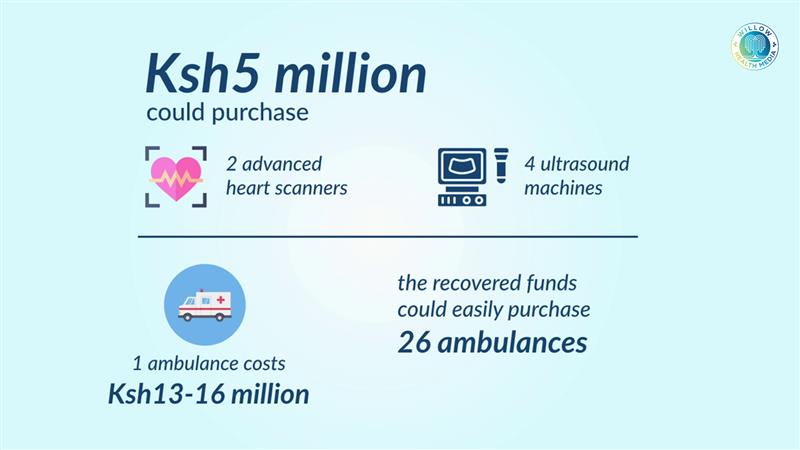

Just Ksh5 million from looted funds could have bought two heart scanners and four ultrasound machines

The government is in the process of recovering Ksh428.6 million of public funds embezzled by former Migori Governor Okoth Obado.

That loot represents almost half of Migori’s Ksh1.9 billion medical services budget for 2021/22. Just this month, the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) auctioned Obado’s apartments in Riara and Greenspan in Nairobi, along with a townhouse in Loresho Ridge, realising Ksh69 million.

With just Ksh5 million from looted funds, the county could have purchased two advanced heart scanners and four ultrasound machines. One ambulance costs between Ksh13-16 million, meaning the recovered funds could purchase 26 ambulances, critical for a county where mothers sometimes give birth by the roadside during transit to hospitals.

In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) donated 15 ambulances to support maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health in six counties, including Migori. Yet even with this support, Migori had a maternal mortality rate of 412 in 2019, according to an IPF (Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis) factsheet. In 2015, the county recorded the highest maternal mortality rate in the entire country.

Over a dozen years since Devolution promised to deliver healthcare to the grassroots, Migori remains unable to adequately staff and stock health facilities built during Obado’s tenure of brick-and-mortar frenzy.

We have not seen any medicine brought here or doctors employed; no one gets help

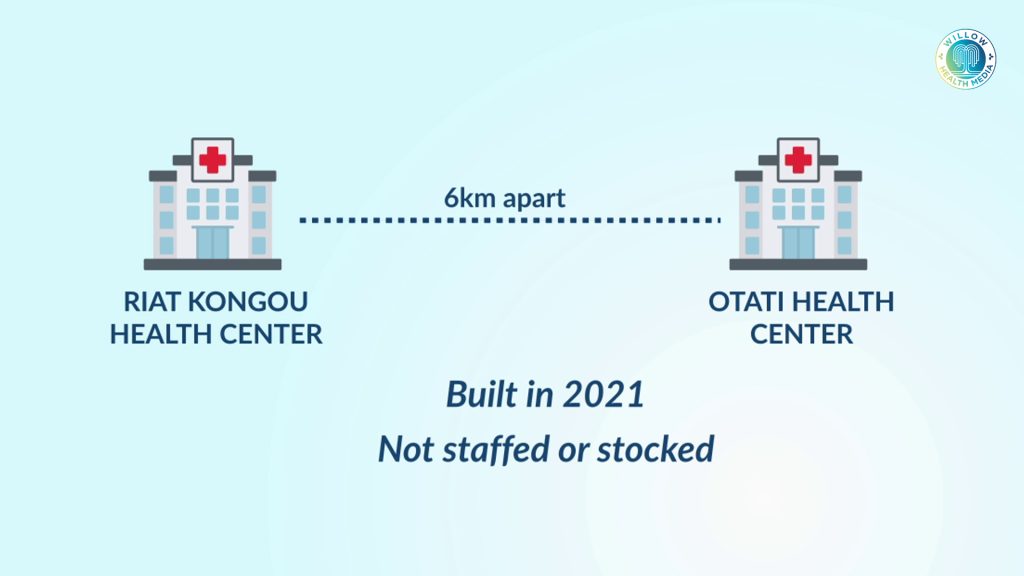

Riat Kong’ou Health Centre in Kanyasa Ward, for instance, was constructed in 2021 about six kilometres from Otati Health Centre, to serve hundreds of patients. But it has never been stocked or staffed. There has been no handover or opening ceremony since its completion.

“We have not seen any medicine brought here or doctors employed; no one gets help from there,” said George Oyugi, a resident of Riat Kong’ou, who remembers a mother who died two years ago because the poor road to Karungu delayed her trip to the hospital.

“When it is raining, and people have to use boda bodas, yet it is hilly, so they sometimes give birth by the roadside or even lose their lives before getting to the hospital,” Oyugi said.

A 2024 study by Okundi and Varol found 248 health facilities in Migori County, including 33 hospitals, 26 health centres, six private maternity and nursing homes, 137 dispensaries, and seven standalone Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT) stations. Of these, only 43 public and 13 private health facilities were equipped to provide basic healthcare services.

According to the Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Council (KMPDC) register, Migori has 167 public health facilities: 12 are Level 4, 23 are Level 3, and 132 are Level 2.

Auditor General’s Report flagged a questionable payment of Ksh61 million to KEMSA

The study also found that the accessibility of hospitals on weekends in Migori was 60 per cent, as medics, especially in lower-level rural facilities, did not work most weekends. Overnight accessibility of healthcare stood at just 49 per cent. As of 2018, Migori County had 31 medical officers and one dental officer, according to the KMPDC.

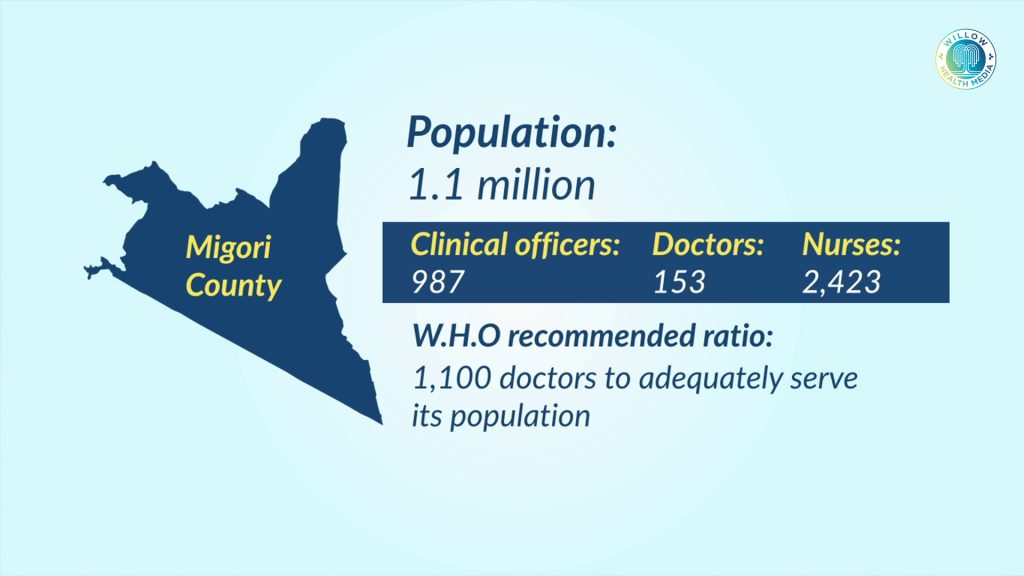

A 2022 study titled Investing in the health workforce in Kenya: trends in size, composition and distribution from a descriptive health labour market analysis, published in BMJ Global Health, revealed a critical shortage of healthcare workers in Migori County. The study found that Migori, with a population of 1.1 million people, had 987 clinical officers (4 per cent of Kenya’s total), 153 doctors (1.2 per cent), and 2,423 nurses (2.2 per cent).

Harrison Odoyo, a resident of Kanyadiang’a village near Otati Health Centre, said the facility serves a large area, including people from as far as Magunga. However, the lack of healthcare workers and frequent drug shortages disadvantages everyone who relies on it.

The Auditor General’s Report for 2021/22 flagged a questionable payment of Ksh61 million from Migori County to the Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (KEMSA), noting the absence of inspection reports and signed delivery vouchers from health facilities that were supposed to receive the medical goods.

But Odoyo laments that Otatio Health Centre “Sometimes they don’t even have malaria medicine. Even Coartem and Panadol can sometimes miss here,” and patients are often told to buy their own medicines. “If they could only employ more doctors and ensure that there are enough drugs, then that would be good.”

Health facilities reported as ‘complete’ were found unfinished and poorly constructed

A 2023 EACC study on procurement and financial corruption in the health sector found that county governments reported some health facilities as ‘complete,’ but inspectors found them unfinished and poorly constructed. The study, however, did not delve into the impact of corruption on health provision, specifically adequate staffing and stocking of essential drugs.

Another 2023 study by Munywoki and other researchers on the impact of corruption on efficiency of health systems listed theft, embezzlement, misuse of public property, informal payments, hiring and training staff based on connections, and paying for low-quality goods, services and infrastructure as culprits.

The study reported that these practices lead to “direct loss of health sector resources, increase operational costs, poor quality of care, reduced staff motivation and productivity, and reduced access to healthcare services,” the study reported.

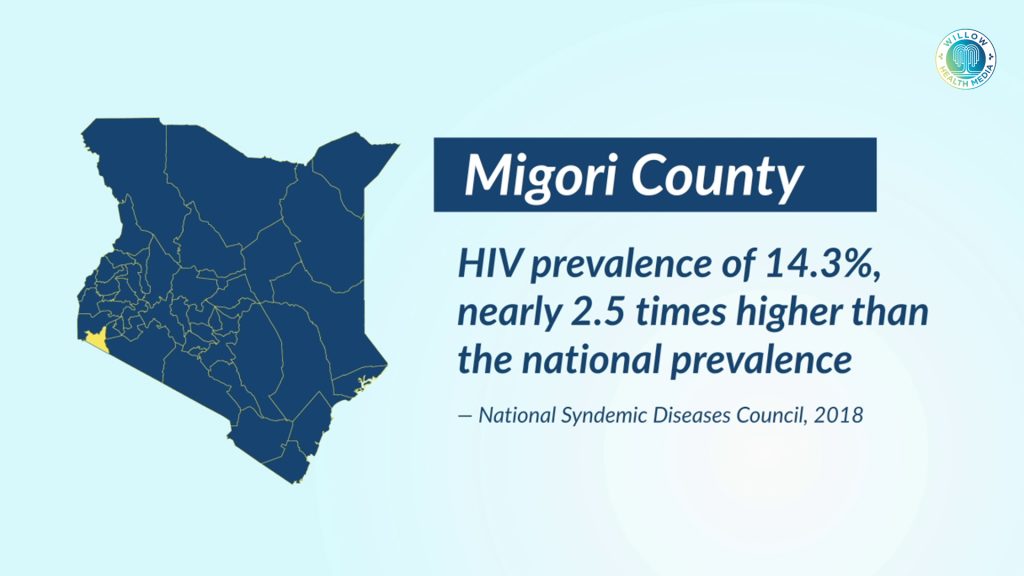

Anita Musiega, a health economist with KEMRI-Wellcome Trust, said rampant corruption is setting up Kenya for aid dependence. She said that the Global Fund has reduced funding for HIV in Kenya by $53 million annually. If equally shared among counties, every county would receive about $1 million each (Ksh130 Million).

Women deliver babies by flashlight in facilities lacking the most basic amenities

“If the people entrusted with power were not stealing from the counties, they would naturally bridge the funding gap left by the Global Fund,” she said.

This is particularly critical for Migori, which has a high HIV prevalence of 14.3 per cent, nearly 2.5 times higher than the national prevalence, according to 2018 data by the National Syndemic Diseases Council (NSDC).

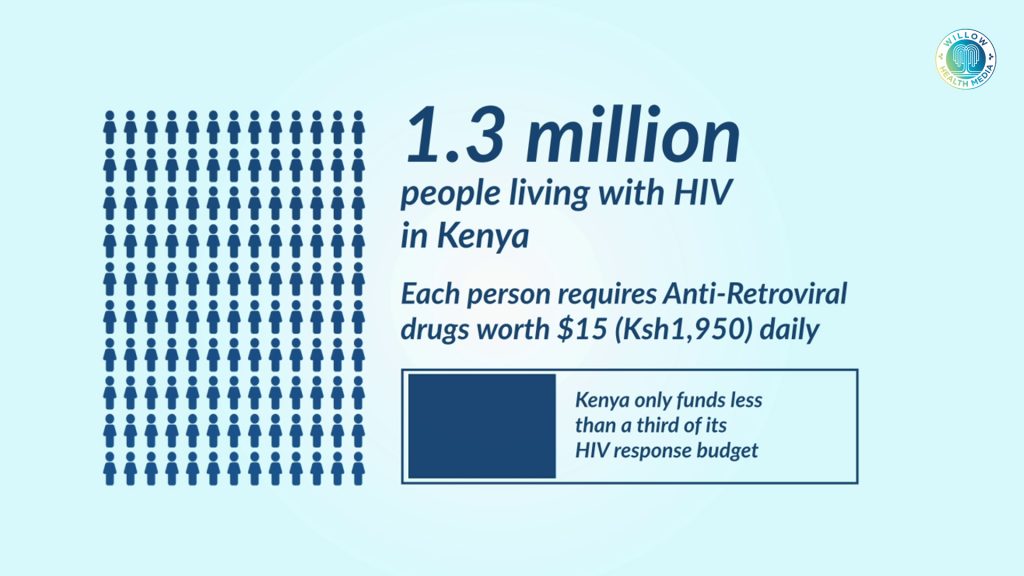

Musiega explains that Kenya has over 1.3 million people living with HIV (not including those with TB), each requiring Anti-Retroviral drugs worth $15 (Ksh1,950) every day. But Kenya only funds less than a third of its HIV response budget, depending majorly on the Global Fund and other donors.

“If we were able to address corruption as a country and build systems that work, then we would do much better in providing healthcare for our people,” she said.

Yet according to the Kenya Primary Health Care Strategic Framework 2019-2024, the government of Kenya is committed to strengthening Primary Health Care (PHC) starting from the community, dispensaries and health centres.

For residents of Otati and Kanyasa, that commitment remains unfulfilled. While some residents travel to Sori Lakeside or St Camilus in neighbouring Karungu town, those who rely on Otati Health Centre continue to face challenges: no proper wards, no electricity, no water, inadequate medicine, and insufficient staff.

Had the millions looted by Obado been used for healthcare, Otati Health Centre could have been properly staffed and supplied with enough beds and power. Instead, mothers like Adhiambo’s niece continue to deliver babies by flashlight in facilities that lack even the most basic amenities.