For millions of women who have waited generations for medical breakthroughs tailored to their bodies, the Gates Foundation’s message is simple: help is finally on the way

The Gates Foundation announced a historic $2.5 billion (over Ksh337 billion) investment in women’s health research by 2030, focusing on underfunded areas, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

This is their largest single commitment to women’s health in the organisation’s history.

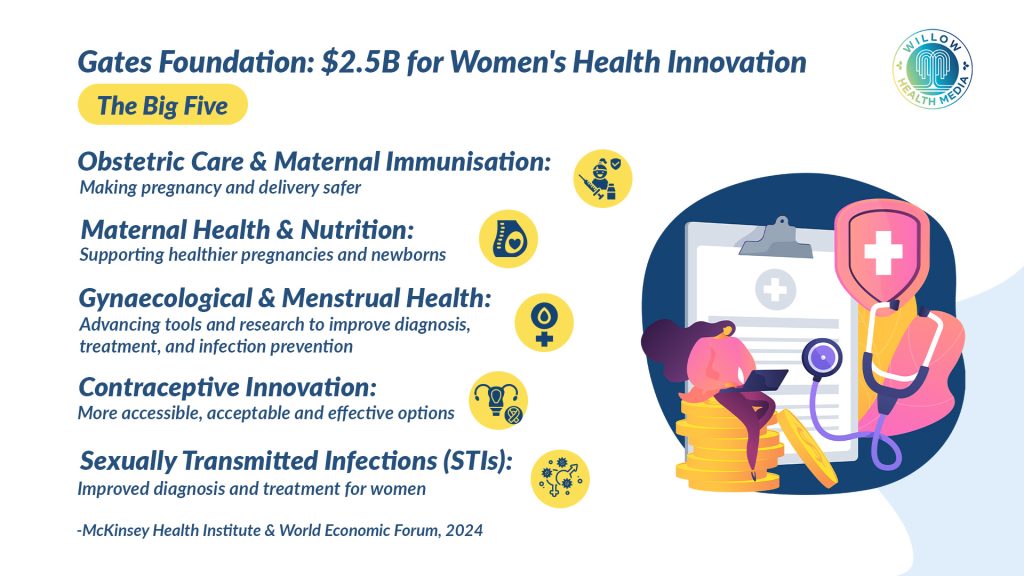

The ambitious initiative will support the advancement of more than 40 innovations across five critical areas: obstetric care and maternal immunisation, maternal health and nutrition, gynaecological and menstrual health, contraceptive innovation, and sexually transmitted infections treatment and prevention.

“For too long, women have suffered from health conditions that are misunderstood, misdiagnosed, or ignored,” said Dr Anita Zaidi, president of the Gates Foundation’s Gender Equality Division.

“We want this investment to spark a new era of women-centred innovation, one where women’s lives, bodies, and voices are prioritised in health research and development.”

Chronic underinvestment has left critical conditions deeply under-researched

The announcement comes as women’s health research faces a stark funding crisis. According to a 2021 analysis by McKinsey, just one per cent of healthcare research and innovation funding is invested in female-specific conditions beyond oncology.

This chronic underinvestment has left critical conditions like pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, heavy menstrual bleeding, endometriosis, and menopause, which together affect hundreds of millions of women, deeply under-researched.

Dr Rasa Izadnegahdar, a paediatrician who leads the Maternal, Newborn, Child Nutrition and Health team at the Gates Foundation, emphasised the urgency of addressing these gaps.

“This is a critical time for this announcement because women’s health is a critical area of investment,” he said. “We believe these areas of research in maternal health, women’s health and adolescent girls and understanding what could be achieved, is one of the most impactful and yet underfunded and understudied areas.”

He highlighted global science institutions working on vaccine-preventable diseases and new technologies for diseases. Yet, they still neglect and underfund key women’s health issues like preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, contraception, and microbiome research.

Areas of potential research include vaginal microbiome, and non-hormonal contraception options

“If we want to see the kinds of impact in reducing maternal and newborn death and improving the lives of families, those are critical investment areas and goals that are the cornerstones of the Gates Foundation’s work,” Dr Izadnegahdar explained.

The funding follows Bill Gates’ pledge to prioritise women’s and maternal health over the next two decades.

The $2.5 billion will target five key areas where innovation can save lives, address women’s needs in poorer countries, and reduce misdiagnoses due to medical gaps.

“Women were first required to be included in clinical research only as recently as 1993, meaning decades of medical breakthroughs were developed primarily based on male physiology,” said Dr Ru-fong Cheng, the Director of Women’s Health Innovations.

“Even more telling, it wasn’t until 2016 that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) began requiring researchers to provide disaggregated reports on their research findings, separating results by sex rather than combining them into generalised findings.”

For years, medical research treated male and female bodies as the same- even after women were included in studies. With accurate sex-specific data only available for about 10 years, many women’s health issues remain poorly understood. That’s why this $2.5 billion investment isn’t just late-it’s a game-changer.

This funding will drive breakthroughs in vaginal microbiome research, new preeclampsia treatments, and non-hormonal contraception while supporting data collection and advocacy to deliver solutions—building on the Foundation’s proven track record of partnering with researchers in lower-income countries.

“Much of our microbiome work has been, for example, conducted in Kenya, including with partners at KEMRI (Kenya Medical Research Institute), a lot of our ultrasound work too, has been done in Kenya,” Dr Izadnegahdar said.

This approach reflects the Foundation’s strategy of building local capacity rather than simply funding external research, “then that creates the momentum for this to continue to grow of its own rather than being catalysed per se alone by the Gates Foundation,” he explained.

Investing in women’s health has a lasting impact across generations

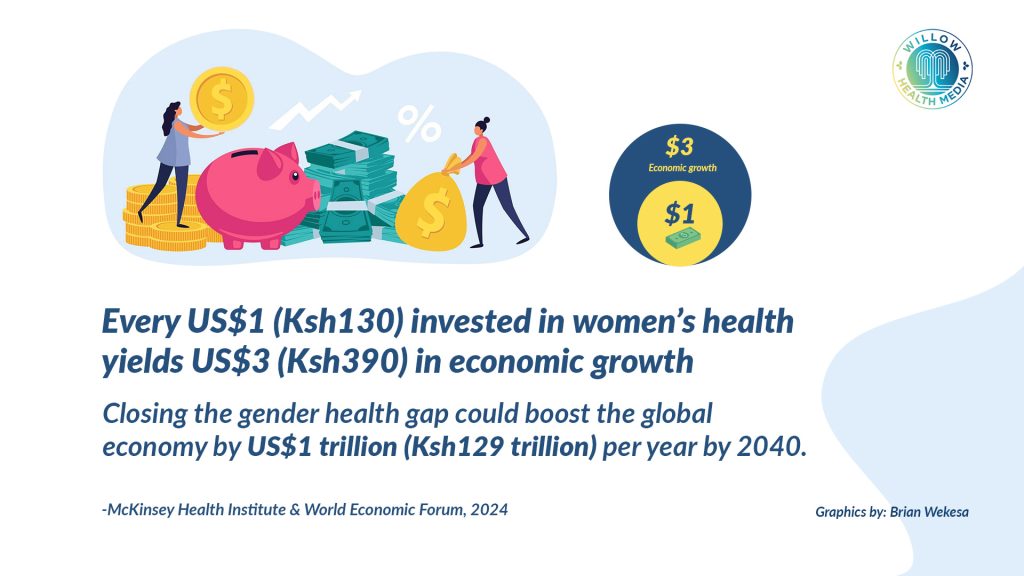

Beyond the moral imperative to address women’s health needs, the investment carries significant economic implications. Research indicates that every $1 (Ksh130) invested in women’s health yields $3 (Ksh390) in economic growth, and closing the gender health gap could boost the global economy by $1 trillion (Ksh129 trillion) annually by 2040.

“Investing in women’s health has a lasting impact across generations. It leads to healthier families, stronger economies, and a more just world,” said Bill Gates, chair of the Gates Foundation. “Yet women’s health continues to be ignored, underfunded, and sidelined. Too many women still die from preventable causes or live in poor health. That must change. But we can’t do it alone.”

Prof Moses Obimbo is a researcher and Calestous Juma, Science Leadership Fellow working on vaginal microbiome diagnostics.

He highlighted key challenges facing women’s health in low- and middle-income countries from adolescence through motherhood to menopause as including “poor pregnancy outcomes, postpartum haemorrhage, pregnancy-related hypertension and infections, neglected tropical diseases, non-communicable diseases like gestational diabetes, gender-based violence, and harmful traditional practices.”

Prof Obimbo said Africa accounts for only 18 per cent of the global population and 20 per cent of all births, but sub-Saharan Africa bears the burden of more than 50 per cent of women’s health-related challenges and maternal mortality worldwide.

The statistics, added Prof Obimbo, are alarming: in 2023 alone, about 182,000 African women died from pregnancy-related complications, with postpartum haemorrhage contributing to 40 per cent of these deaths and preeclampsia accounting for another 20 per cent.

“These preventable deaths stem from lack of timely diagnostic tools, healthcare workforce shortages, inadequate training, and weak health systems with poor referral mechanisms. While emerging fields like microbiome science show promise for preventing preterm birth, preeclampsia, and stillbirth, they remain severely underfunded and lack sufficient data for developing proper diagnostic tools.”

Dr Bosede Afolabi, professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at the College of Medicine, University of Lagos, welcomed the commitment. “We see the consequences of underinvestment in women’s health innovation every day when women suffer needlessly, and sometimes lose their lives, because of the gaps in how we understand and treat conditions that uniquely affect them,” she said.

Prof Obimbo emphasises that beyond the Gates Foundation’s investment, greater commitment is needed from other funding agencies, governments, and stakeholders to deploy new technologies, including Artificial Intelligence (AI), to transform women’s health outcomes across Africa.

Zaidi acknowledged the scale of the challenge ahead: “This is the largest investment we’ve ever made in women’s health research and development, but it still falls far short of what is needed in a neglected and underfunded area of huge human need and opportunity.”

The initiative is a systematic attempt to reorient how the global health community approaches women’s health challenges

The success of these investments will depend not only on scientific breakthroughs, but also on public awareness and advocacy. Izadnegahdar emphasised the critical role that media and public communication play in this effort.

“Everything from understanding what the gaps are, what the needs are, making sure that there’s a clear recognition in the population of ‘if these things are not there, what happens’,” he said. “If you leave something neglected, what is the societal cost of that? What is the individual cost of that?”

Beyond funding, the Gates Foundation is betting that this concentrated effort can break through decades of institutional neglect and spark the kind of sustained innovation that women’s health has long deserved.

As the Foundation works toward its long-term goals through 2045 – ending preventable deaths of mothers and babies, eliminating deadly infectious diseases for the next generation, and lifting millions out of poverty – this women’s health initiative stands as perhaps its most ambitious attempt yet to address the systemic inequities that have left half the world’s population underserved by medical research and innovation.