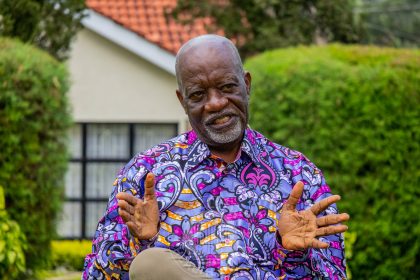

Africa’s healthcare system is a story, not of scarce resources, but of plunder, laments Prof Khama Rogo. Life-saving machines rust while bureaucrats profit from phantom workshops.

A plan to save Kenya’s public hospitals with modern, leased medical equipment was instead sabotaged by the very leaders tasked with its success.

According to public health expert, Prof Khama Rogo, Kenya’s Managed Equipment Services (MES), was a Public-Private Partnership in which the Ministry of Health contracted private sector providers to supply, install, maintain, and replace equipment in public hospitals.

It was meant to rid Kenya of the eyesore of unused or misused medical equipment rotting in “boxes that had never been opened or had been rained on under leaking roofs.”

Prof Rogo reasons, had the same equipment belonged to the private sector, they would have taken care of it, driven by business and reputational grounds.

“In the West, they lease functionality. You are guaranteed 80 per cent uptime, and the provider replaces equipment when it breaks down; they can repair it within 24 hours,” says Prof Rogo.

Governors rejected free equipment monitoring system

But some people in the Ministry had other ideas.

Once the equipment was supplied and installed, big shots at Afya House and governors rejected the free equipment monitoring system for the machines from the suppliers, General Electric Corporation (GEC) and Toshiba. The system would indicate the equipment’s state anytime, including when it was repaired, by whom, what was replaced, and the cost.

GEC was offering free training for health technicians in its Karen nerve centre in Nairobi. Governors didn’t want the equipment because it was contracted by the Central Government, denying them a lucrative rent-seeking opportunity.

Afya House, therefore, brought in a middleman who can never be cheaper than the manufacturer. The new kids on the block would lease everything, cutlery included.

“We create our failures,” says Prof Rogo, who lists his saddest memories as including visits to Mali, Mauritania and other Sahel countries where bands would play, guards of honour mounted and brass plaques mounted on walls during opening ceremonies.

New linen had been stored for display as patients froze

Days later, the fresh linen would be transported back now that nabobs from government had been flown back to the capital, never mind the new linen had been stored for display as patients froze in the wards.

Prof Rogo remembers Tanzania’s first President, Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, telling him how he enjoyed retirement because, after decades, his nostrils were not being assailed by the smell of fresh paint, opening institutions that were of little use to the ordinary Tanzanian.

Prof Rogo also recalls a time when AMREF was the only health NGO, and medical workers met in Special Health Sector Training Institutes, SHSTIs.

“We didn’t go to hotels,” he says, arguing that the huge amounts spent on hotels should be spared to revive and expand the SHSTIs.

But this disease is incurable, as “The KNH board”, he says, “prefers to meet at the Silver Springs Hotel as its boardroom lies idle.”

So, is Africa condemned to live or die from a sick public health sector for good?

“Until this DNA of corruption is wiped out, the health sector will suffer,” he says, falling short of recommending the physical annihilation of the corrupt and their networks, the way Jerry Rawlings did in Ghana.

Divine interference saw them being awarded a Sh30 million contract

“The sacrifices we need for a new beginning are more painful than we can contemplate,” he opines. Juxtaposing the solution to the problem, he cites the case in Kenya where somebody told a parliamentary committee of a divine interference that saw them being awarded a Sh30 million contract to supply medical equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In a country he wouldn’t name, donors funded the importation of condoms to stem the spread of HIV-AIDS, but bureaucrats had other ideas. A close inspection of the consignment revealed cartons full of Viagra instead of the rubber sheaths.

Prof Rogo has seen over 30 delegations from Africa coming to learn the magic of NHIF, only for corruption to torpedo the hospital insurance fund.

He says the beauty of the defunct NHIF lay in focusing on the household “because poverty is a household thing in Africa, unlike in the West.”

Linda Mama covered the pregnancy, but not the household

He has witnessed strange things at the Linda Mama Initiative, which was initiated by former First Lady Margaret Kenyatta.

“It covered the pregnancy but not the household. If the money that went into Linda Mama was used to cover the indigent, we would have been on our way to Universal Health Care,“ he says.

Indigent refers to people who are financially unable to afford basic necessities.

In the first year, he says, the money did not go to NHIF, which was pressured to settle claims on the promise that it would be compensated by the Treasury. This didn’t happen, throwing the Fund into a financial crisis. An audit would discover that NHIF had settled claims involving male pregnancies!

“How Kenyan men started delivering, we could not explain to the World Bank side, but we told them men are unique in Kenya.”

Next in the list of infamy was Edu Afya, the now-discontinued Sh4-billion medical insurance scheme for secondary school students.

Donor health workshops biggest cause of absenteeism in the health sector

An illustration of misplaced priorities, Edu Afya forgot that the demographic it was covering was the healthiest, as it left the ailing and ageing vulnerable segment of the population to bear the brunt of sickness.

Prof Rogo could give more depressing examples, including Kenya’s donor-driven health workshops bonanza, which he says is the biggest cause of absenteeism in the public health sector, as doctors and administrators cash in on a per diem frenzy.

“Some ‘attend’ as many as three workshops a day. All they need is to sign forms. Some are paid for 600 days in a year,” he says.

But why would anyone allow this profligacy? Because, Prof explains, donors say nobody would bother to attend the policy-generating workshops without per diems.

Prof Rogo is persuaded that the despicable state of public health services in Kenya has little to do with financial allocations.

There is not a single thing Nairobi Hospital can do that KNH can’t

“The combined budgets of the three leading hospitals, KNH, Moi and Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral hospitals are bigger than what we give to all counties on top of the money they collect,” he argues, wondering why such institutions cannot offer world-class health services.

“There is not a single thing that Nairobi Hospital can do that KNH can’t,” he says, explaining that the biggest driver of healthcare costs in Africa is not high charges by private hospitals but the dysfunctionality of the public sector.

“If KNH can do renal transplants correctly, Nairobi Hospital will drop charges,” he argues, citing the dropping MRI charges in private hospitals when the government introduced the Managed Equipment Scheme.

No wonder Prof Rogo has predicted that debate on the health sector in Africa will soon determine the presidency, because you cannot hide disease.

“If you are coughing now and we don’t tell you it’s TB, it doesn’t disappear”.

Our last question: Is the professor worried that he has made enemies because of his outspokenness about graft and inefficiency in the public health sector?

Not really!

“I’m in my turf. I only comment on health. In health, I’m safe. I will say it; I will defend it. I will talk about my village, my country and my continent. It’s easier to defend the truth than to defend lies because it’s very difficult to remember what the last lie was. I’ve kept my linkages, my sanity and most importantly, my integrity.”