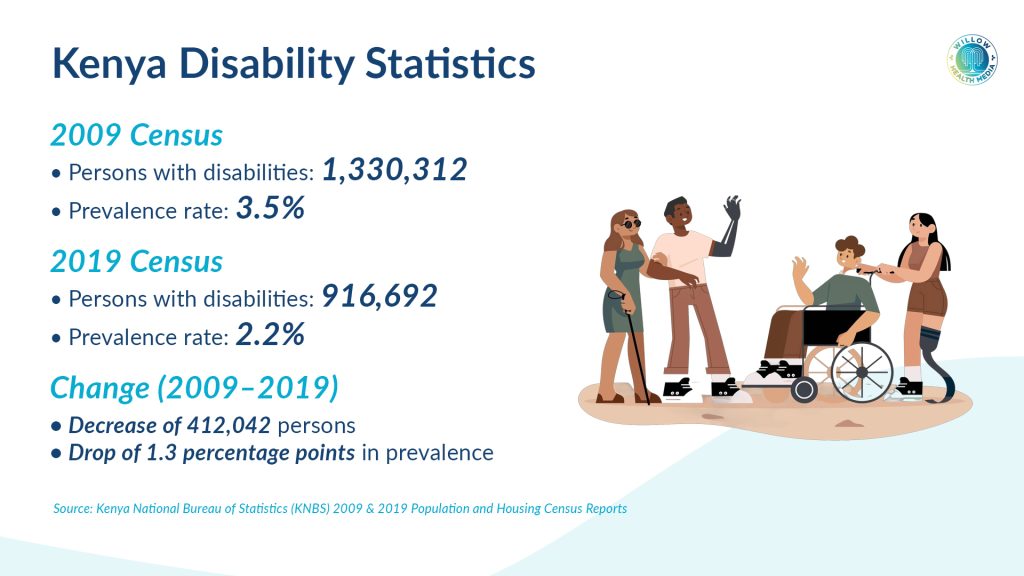

Kenya lacks accurate data on the number of people living with disabilities. Without reliable figures, the government cannot plan or allocate resources effectively for this population, and may even lose the political will to address their needs

Back in 1959, the fight for disability rights in Kenya began, not with legislation, but with love. A 26-year-old blind man from Makueni named John Kimuyu did the unthinkable: he married Ruth Holloway, a 35-year-old white British missionary who was his teacher.

Their union, crossing lines of race, age, and disability amid the tensions of colonialism, sparked outrage from the British community.

But Kenyans with disabilities saw something else: glaring injustice! Black men, including President Jomo Kenyatta, had freely married white women without interference, so why would Kimuyu’s case be different? The answer was obvious: his blindness.

Protesters took to the streets, demanding that the president protect the rights of people with disabilities to marry whomever they chose. That moment in 1959 marked the recorded beginning of Kenya’s arduous journey toward disability inclusion.

And yet, more than six decades later, people with disability in Kenya still struggle with widespread stigma and discrimination, limited access to education and healthcare, and severe economic hardship due to high unemployment and poverty.

Picture a parent racing against time, torn between keeping their job and taking their child to therapy three times a week. Imagine a talented professional forced to retire just as their career hits its stride, simply because they entered the workforce late due to barriers in education.

Now, think of someone standing at a busy intersection, hoping a stranger will notice and help them cross the road, not because they lack ability, but because the city lacks consideration.

These are the daily realities of millions of Kenyans with disabilities. But if Senator Crystal Asige has her way, these struggles may soon be stories of the past.

Disability does not discriminate, but society has made it look dirty and pitiful

Senator Asige is calling for a national reckoning on disability inclusion, warning that Kenya cannot implement its new disability law without first confronting the country’s long-standing failure to count persons with disabilities accurately.

Speaking to editors and journalists at a sensitisation session in Nairobi, the Senator, who lost her sight gradually in her teens and early adulthood, urged the media to challenge entrenched stereotypes and help Kenyans understand the significance of the Persons with Disabilities Act, 2025, which was assented to on May 8 and commenced on May 27.

“If you leave here remembering nothing else, please remember this,” she told the room. “Disability itself does not discriminate. It is just an identity like being black, like being a woman… But society has managed to make disability dirty and pitiful. Disability does not discriminate; it’s people and systems that do.”

Her lived experience, she said, shaped the law from the ground up. “I have lived on both sides of the street as an abled girl and now as a disabled woman. The journey from one side to the other has been both my hurt and my healing, my confusion and my clarity, my prison and my power.”

At the heart of Asige’s advocacy is a simple but stark problem: Kenya does not know how many people live with disabilities.

The 2019 census recorded 916,692 persons with disabilities, a dramatic drop from 1,330,312 in 2009. “Where did they go? Could mass healing or mass death of people with disabilities have taken place?” she asked. The prevalence fell from 3.5 per cent to 2.2 per cent, far below the World Health Organization’s estimate that 15 per cent of any population lives with a disability.

“If we are not counted, we do not count,” Asige said, calling for a special disability census budgeted at Ksh1 billion. Without reliable numbers, she warned, Kenya cannot plan or budget effectively. “When the disability population appears to shrink on paper, so does political will.”

One of the most far-reaching reforms in the Act addresses a daily burden on thousands of families. Section 20 requires the Ministry of Education, together with other ministries, to provide school-based therapy, including speech and occupational therapy, physiotherapy, audiological assessments, and rehabilitation.

“The reality is that parents and caregivers are forced to choose between going to work and taking leave as often as two or three times a week to take their children to therapy in hospitals,” Asige said. “These regular leave requests grow a quiet frustration with employers and become the covert excuse to dismiss these parents, leading to even more poverty.”

Companies committed to disability inclusion record up to 30 per cent higher revenue, double the net income, and 72 per cent higher productivity

Section 24 entitles persons with disabilities to free medical care in public facilities, including free medical assessment reports required for disability registration.

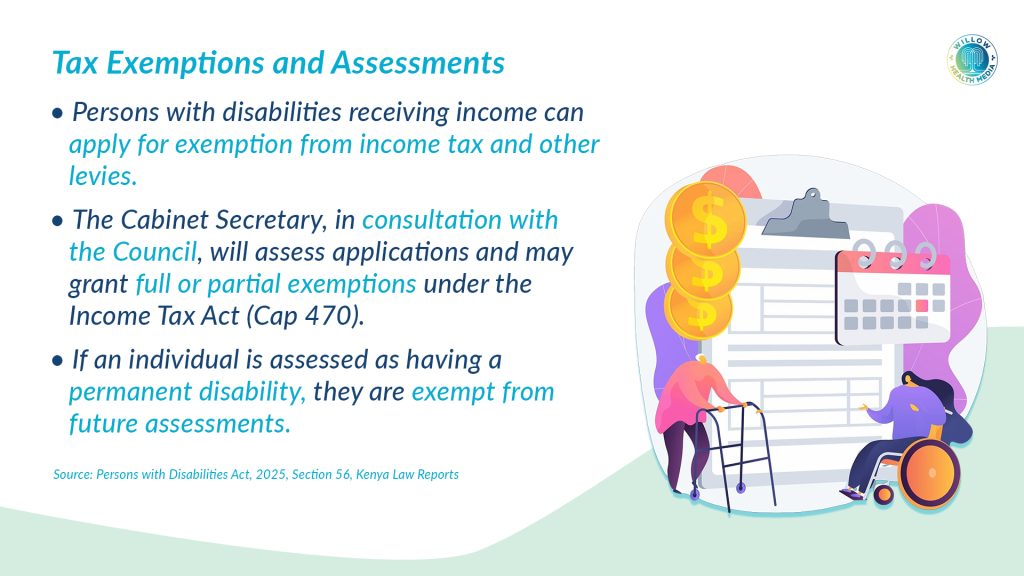

The law also introduces significant tax relief. Under Section 57, the Treasury Cabinet Secretary may grant income tax exemptions to parents or guardians caring for a person with a certified severe disability. The Ministry of Social Protection may separately offer a long-term monthly cash transfer to indigent households providing full-time care.

Regulations are being drafted to define “severe disability”, but Asige says the criteria will differentiate between those needing occasional support and those requiring “substantial daily assistance.”

The Act eliminates mandatory reassessments for individuals with demonstrable permanent disabilities, enabling them to enjoy a lifetime tax exemption.

“To undergo reassessment every five years is only targeted at persons with disabilities and ends up being discrimination,” Asige said. “Are men reassessed to confirm they are still men to keep their rights? Are women reassessed to prove they are still women? Of course not.”

Some reassessments took more than a year, she noted, during which people lost tax benefits without reimbursement. “It’s a matter that necessitates urgent attention and corrective measures.”

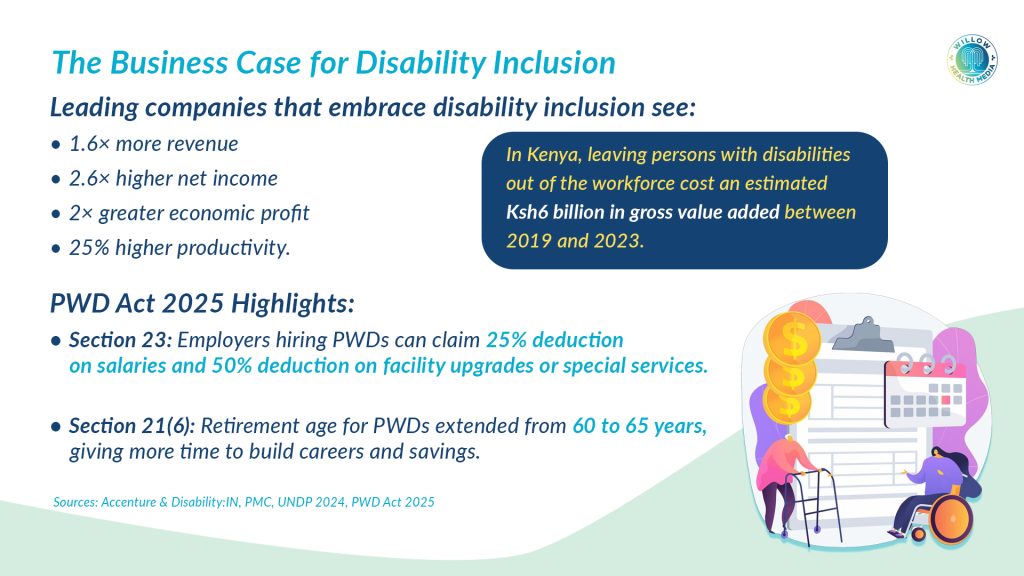

Section 21 requires employers with at least 20 staff to reserve five per cent of jobs for persons with disabilities. Asige argues this is not tokenism but recognition of untapped economic potential.

“Many tend to believe that hiring PWDs is burdensome and lowers productivity, which is a big myth,” she said. She cited global research showing companies committed to disability inclusion record up to 30 per cent higher revenue, double the net income, and 72 per cent higher productivity, with 90 per cent of HR managers saying employees with disabilities meet or exceed expectations.

Kenya, she added, loses an estimated 7-10 per cent of GDP annually because people with disabilities are excluded from the workforce.

The Act also extends the retirement age for persons with disabilities from 60 to 65, acknowledging that many enter the workforce later due to educational barriers.

Premises considered inaccessible for persons with disability will attract a fine of up to Ksh5 million or five years in prison

Private employers who hire persons with disabilities will be eligible for a 25 per cent tax deduction on wages paid, and an additional 50 per cent deduction for expenses incurred to improve accessibility or provide reasonable accommodation. The Act guarantees a barrier-free environment, requiring all public and private institutions to adhere to accessibility standards.

If premises or services are deemed inaccessible, Section 31 empowers the Council to issue an Adjustment Order, with non-compliance attracting a fine of up to Ksh5 million or five years in prison.

Digital accessibility is now a legal requirement. Public and private institutions must provide information online in accessible formats. Television stations must provide Kenya Sign Language inset, captions in newscasts and educational programs, and in all broadcasts of national or international significance.

“Every time I visit a government website or scroll through social media, I think about how empowering digital technology can be,” Asige said. “But I also know what it feels like when those simple online tasks become frustrating barriers.”

The Act introduces tough penalties. Discrimination attracts fines of up to Ksh2 million or two years in prison. Harmful practices, including witchcraft accusations, abandonment, concealment, or ritual killings, carry life imprisonment. Using a person with disability to beg now carries up to Ksh2 million in fines or two years in prison.

“I found it impossible to believe that using PWDs to beg on our streets was never deemed a criminal offence before this Act,” Asige said.

Beyond legal reforms, Asige said Kenya must change how it understands disability.

“People with disabilities are incredibly creative if you decide to think that way. Wheelchair users walk without moving; blind people read without seeing; deaf people talk without speaking.”

She urged the media to create programming that normalises inclusion, “for instance, a children’s program where kids with and without disabilities learn and dream together.”

Section 26 requires broadcasters to provide one hour of free airtime monthly for disability awareness, a chance, she said, to replace pity with possibility.

Asige ended with a reminder that disability can affect anyone at any time, stating that in a country where 15 per cent of the population likely has some form of disability, inclusion isn’t charity, but justice and humanity.

“We must no longer agonise. We must now organise,” she said. “The question is: Will Kenya answer the call?”