Women over 40 have the highest chances of pregnancy loss, but there are medical interventions for recurrent miscarriages depending on the underlying causes.

Behind closed doors, countless Kenyan women face the repeated trauma of miscarriage, a silent, isolating experience. Margaret Nyawira knows this grief better than most: She suffered four miscarriages and lost six babies before delivering a healthy one in her ninth pregnancy.

Her story began when she dropped out of school due to lack of fees at just 16. She became a house help and shortly opted for marriage for survival. But her journey into motherhood ended in tragedy during her first pregnancy. “I woke up feeling dizzy and fainted.” Medics at the hospital termed her case an emergency. “Only God saved me, I thought I was going to die,” she recalls.

Doctors discovered an ectopic pregnancy and removed her left fallopian tube. They later found that her other tube was blocked, and her uterus was too weak to carry a child.

Surgery was recommended, but Nyawira never underwent it. Instead, her doctor recommended her to participate in a research study at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), where “They unblocked the (fallopian) tube without undergoing surgery. The tube was simply flushed, and it became unblocked,” she explains.

Soon after, she conceived again, but the baby was born with severe deformities. “From the chest downwards, all his intestines were outside. They called it omphalocele,” says Nyawira, who subsequently lost five pregnancies, each loss chipping away at her spirit.

Omphalocele is a birth defect where the baby’s abdominal wall doesn’t close fully, causing organs to protrude through the umbilical cord. A 2022 review found a 4.47 per cent prevalence among congenital defects in Sub-Saharan Africa.

It emphasised the need for better perinatal screening and early diagnosis to improve survival, noting that such services are still unevenly available.

Thankfully, in her sixth pregnancy, Nyawira delivered a healthy baby boy who “Looked fine, weighed three kilos, but his breathing was weak. The doctors said he was in distress,” and the boy died two days later.

For Nyawira, the pain was not only medical, but also social. At her baby’s burial, her mother-in-law mentioned how her many pregnancies “always end in the grave” and if another baby died, “You already know where to take it.”

Nyawira ‘s husband was convinced to marry another woman. The grief pushed her into depression, high blood pressure, and psychiatric help.

Years later, in her second marriage, another pregnancy ended in miscarriage at three months in between long hospital stays, but finally, her prayers were answered in her ninth pregnancy “When I woke up in the theatre and could hear a baby crying in the distance. I broke down in tears.” That child is now 14 years old.

But even after this joy, grief continued as she lost two more babies, and her second marriage ended. Later, after treatment for fibroids and ovarian cysts, she became pregnant with twins. One died shortly after birth. The other survived and is eight years old today. In total, Nyawira has endured four miscarriages and lost six babies.

Faith Mwende, a nurse, has endured five miscarriages in nine years; each one leaving behind grief, unanswered questions and hard-learned lessons.

“The first miscarriage was in 2016. It wasn’t a planned pregnancy, but an ultrasound confirmed it after two months. But I was bleeding during a checkup a month later. After a scan, I was told there was no baby in the sac, which was removed at the theatre,” she recalls.

Mwende’s second pregnancy ended in miscarriage at three months. Despite meticulously following medical advice during her fourth and fifth pregnancies – including medication and anti-D injections for women with negative blood groups – she miscarried before the fourth month each time.

“I was sad, frustrated, bitter with myself as I didn’t know why I could not carry a pregnancy past three months,” says Mwende, for whom medics could not find anything unusual in her test results, except her blood group: O negative, while her partner is O positive.

When a Rhesus-negative mother carries a Rhesus-positive baby, her immune system may see the baby as a threat and attack it, making the pregnancy fragile, a condition called Rh incompatibility or Rh disease. Globally, about three in every 1,000 babies are affected by Rh disease. Without treatment, about half of affected babies may die or suffer brain damage.

Women with Rh-negative blood are routinely given anti-D shots to prevent complications. The injection is typically administered twice – once on the 28th week of pregnancy and again after delivery, with each dose costing between Ksh5,000 and Ksh15,000.

But despite receiving proper medical care, including the recommended anti-D injections, Mwende still lost all five of her pregnancies.

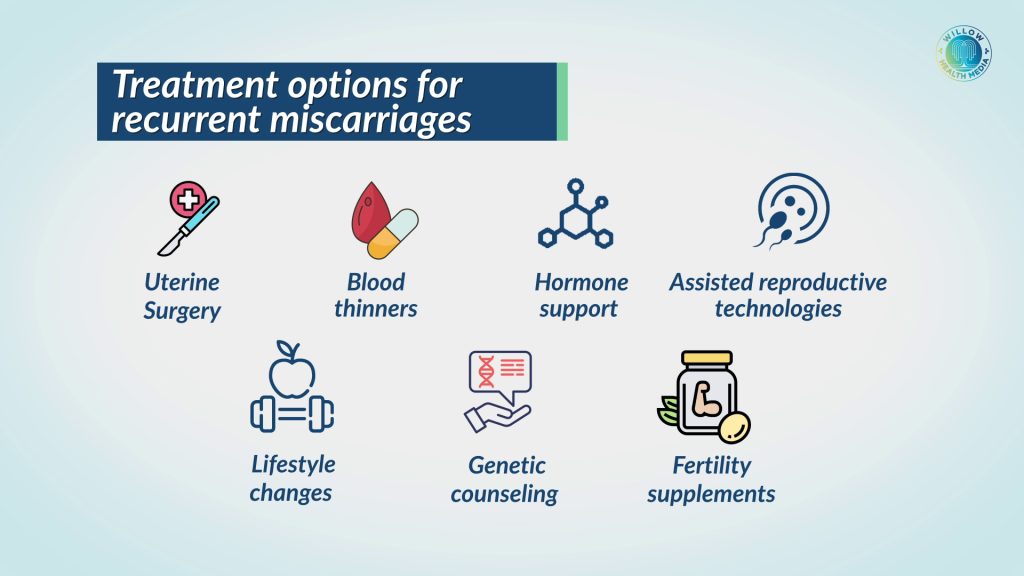

Treatments for recurrent miscarriage exist, but many Kenyan women cannot access them due to high costs and limited availability

Dr Rosa Chemwey, a Gynaecologist and Foetal-Maternal specialist, says recurrent pregnancy loss is losing more than two pregnancies, whether consecutively or not.

“There’s not a single week you would not meet a couple with this condition,” says Dr Chemwey, pegging the reason to more people seeking medical help, as previously couples “would just sit and hope for a good outcome.”

There are many causes of pregnancy loss, but most remain unexplained, as all medical tests could turn normal results, yet pregnancy losses continue.

Dr Chemwey notes that maternal age is one of the most significant factors, as “Women above 45 have a miscarriage rate of over 90 per cent,” she explains. “Whereas at the optimal age of 20 to 25, the miscarriage rate is around 11 per cent.”

As women age, chromosomal abnormalities in eggs rise sharply, lowering fertility and increasing miscarriage risk. Treatments for recurrent miscarriage exist, but many Kenyan women cannot access them due to high costs and limited availability.

For instance, IVF costs between Ksh300,000 and Ksh750,000 per attempt, with donor or advanced options even higher. The pending Assisted Reproductive Technologies Bill, 2022, would regulate and standardise such services, but remains stalled in Parliament. Genetic testing remains costly at around Ksh150,000 per sample, often analysed abroad.

These tests are expensive globally due to the need for advanced machines like DNA sequencers, PCR and microarray scanners, and highly trained specialists such as geneticists and bioinformaticians. Most equipment in Kenya is imported, further driving up costs.

Access barriers persist, especially outside urban areas. Genetic counselling is concentrated in cities, leaving rural women underserved. Even basic interventions can strain finances. Folic acid costs Ksh200–Ksh700, and quality supplements like CoQ10 or omega-3 are rarely stocked in rural clinics.

Managing chronic illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension, or thyroid disease adds further expense through tests, medication, and specialist care.

“When we don’t find an explanation, we give multivitamins specific for the sperm and ovaries, to nurture those cells so that by the time fertilisation is happening, we have a very good quality baby coming out of it,” says Dr Chemwey.

For many couples, the road to overcoming recurrent miscarriage is not only emotionally draining but also financially overwhelming.

A miscarriage is more than a medical issue; it is the devastating loss of a child and the hope of motherhood which counselling psychologist Cleopa Njiru says comes with “Emotions like anxiety – the feeling of, will I be a mother again? And guilt, the feeling that I may have done something, or not done something” and why the baby was lost.

Unaddressed grief can compound with each miscarriage, leading to depression, anxiety, or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). While women bear the physical and emotional burden, men, Njiru says, “go through grief, silently struggling with the emotions of their own loss”, and in most communities, stigma worsens the pain of pregnancy.

In 2015, Mark Zuckerberg revealed that he and his wife, Priscilla Chan, had suffered three miscarriages before the birth of their daughter, Max. By sharing their experience publicly, they aimed to break the silence and stigma surrounding pregnancy loss.

As Zuckerberg wrote, “You feel so hopeful when you learn you are going to have a child… and then they are gone. It’s a lonely experience.” He added that many avoid discussing miscarriage out of fear it will make them seem “defective” or responsible.

Ordinary men are also beginning to speak out. A BBC News feature (2022) highlighted two UK fathers who, after losing babies, launched a podcast and football club for bereaved dads when they found “nothing out there” for men coping with miscarriage.

Matt Dearsley, who had endured four pregnancy losses, said, “It absolutely crushed me.” Another father, Raul, agreed: “People just want to dismiss it or push it under the rug like it didn’t happen.”

Together, their stories expose how men, too, experience deep grief and are challenging the cultural silence around baby loss.

Nyawira recalls the gossip that followed her grief: “After I recovered and continued with my business, people started smear campaigns. They said now that I was blessed, my business was doing well, I bought a car, I had joined the Illuminati and was selling my children to demons to get rich.”

For Mwende, the whispers took a different form. “Some believe it’s witchcraft; others say curses from ancestors or something in the family. But after all those experiences and interactions, I found that most of them are not cultural; they are usually medical-related.”

In the study Exploring Risk Perception and Attitudes to Miscarriage and Congenital Anomaly in Rural Western Kenya, cultural beliefs were linked to miscarriages and congenital anomalies. These included engaging in extra-marital sex, disrespecting traditional norms, or being cursed or possessed. Participants reported that a woman could miscarry or have a child with an anomaly if her husband had an affair or slept with an inherited wife.

Failing to observe traditional customs such as performing marriage rituals, waiting for bride-price payment before pregnancy, or avoiding house construction during pregnancy was also believed to cause complications. Other taboos included sharing a cooking place with a grandmother, assuming elder roles prematurely, planting in someone else’s field, or eating meat from a pregnant cow.

Dr Chemwey notes, “When it comes to fertility, it’s always been pointing towards the woman as a cause.”

Although male infertility is one of the leading causes of infertility, treatment options for men remain limited

That perception is shifting as doctors now emphasise that men play an equally crucial role in conception and pregnancy outcomes. Beyond sperm count, motility, and morphology, sperm DNA health is gaining attention. Damaged DNA, known as fragmentation, can double the risk of miscarriage, highlighting the need to assess both partners rather than focus solely on women.

Male infertility, marked by poor semen quality, is rising. Research in Clinical Chemistry links this to obesity, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and pollution. Although male infertility is one of the leading causes of infertility, treatment options for men remain limited. Experts now stress improving male diagnostics and data collection to develop therapies that stimulate sperm production.

Kenya still lacks sufficient data on recurrent miscarriages. According to the 2022 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS), 10 per cent of pregnancies among women aged 15-49 end in miscarriage. A 2024 Clinical Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology study found 2 per cent of Kenyan women have major uterine anomalies, which may contribute to repeated pregnancy loss, signalling the need for more localised research.

Mwende believes workplaces should support mothers who “need time to grieve and come to reality about what has happened,” but many face work pressure instead. Kenya’s Employment Act (2007) does not mandate bereavement leave, though a 2019 bill proposed five days of paid leave after a family member’s death.

Some employers, however, have progressive policies. The East Africa Breweries Limited grants up to 26 weeks of paid leave for pregnancy loss after 20 weeks and 10 days for spouses; the Teachers Service Commission allows up to 15 days’ compassionate leave; and Safaricom recently expanded bereavement leave to nearly two weeks, covering extended family members, making it among the most progressive in Kenya.

For women like Nyawira and Mwende, recurrent miscarriages are not just medical events – they are battles of the body, mind, and spirit. Their courage to share their stories is a reminder that pregnancy loss is not a private shame but a shared human grief because behind every statistic is a woman, a couple, and a dream of parenthood that deserves compassion and care.