Ghana can learn from Kenya’s past struggles with vaccine hesitancy via false myths on infertility and opposition from parents and religious groups.

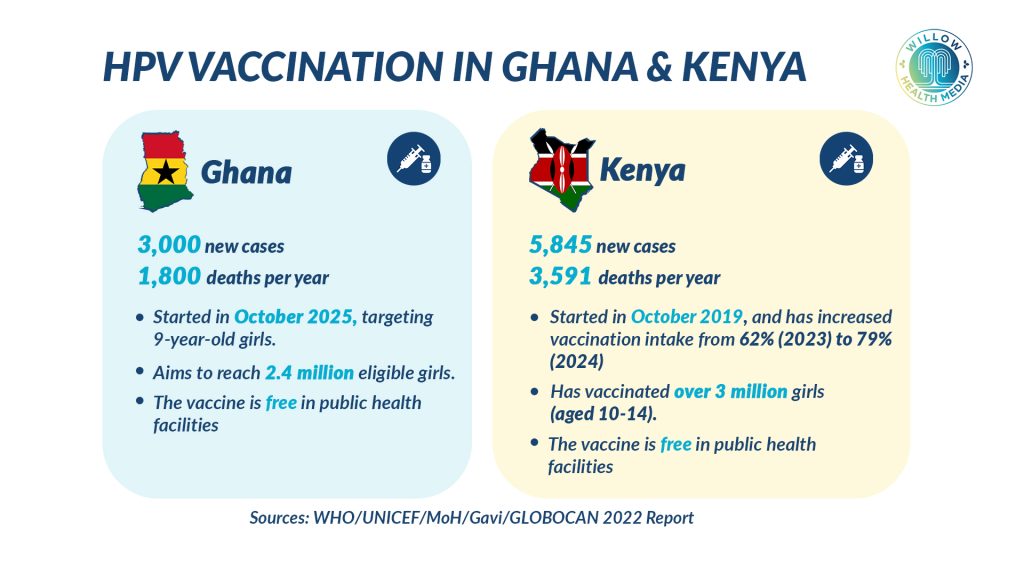

Ghana has become the 29th African nation to introduce the free HPV vaccine, joining Kenya in the fight against cervical cancer, a leading cause of cancer death for women in both countries. The launch of its nationwide campaign in October 2025 follows Kenya’s successful rollout in 2019.

Ghana and Kenya are both fighting cervical cancer by vaccinating girls. While Kenya has more cases and deaths each year, the disease is devastating in both countries. Both countries are giving girls the HPV vaccine for free before they become sexually active. The vaccine stops the types of HPV that cause almost all cervical cancers.

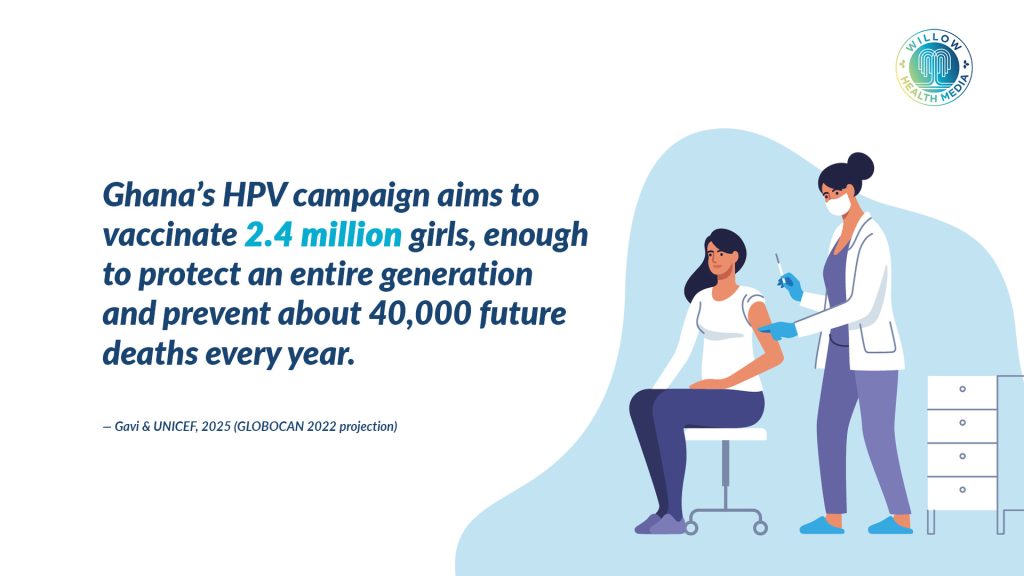

Ghana is targeting 2.4 million girls and has secured 2.5 million vaccine doses, enough to protect a generation of girls and prevent an estimated 40,000 future deaths annually, according to the GLOBOCAN 2022 report.

Both nations are targeting girls before they become sexually active. Ghana is vaccinating girls aged between nine and 14 years, while Kenya is currently vaccinating three million eligible girls, aged 10 to 14 years, according to Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

The World Health Organisation (WHO)-approved vaccine prevents HPV 16 and HPV 18 strains, which are responsible for at least 99 per cent of all cervical cancer cases.

Each girl vaccinated helps end a long-standing cycle of disease across Africa

Kenya and Ghana took different paths to roll out the HPV vaccine. Kenya started cautiously in 2013 with a pilot in Kitui County, reaching 8,455 schoolgirls and 166 out-of-school girls. But prohibitive costs made the pilot unsustainable, leading the Ministry of Health to adopt a new approach and officially include the HPV vaccine in the National Vaccines and Immunisation Programme (NVIP) in 2019.

Ghana, learning from other African countries, has moved faster. It launched a comprehensive strategy from the start, using health workers to deliver vaccines in schools, health centres, and mobile clinics to reach both in-school and out-of-school girls, even in remote areas.

“Today, Ghana is turning promise into action and advancing the fight against cervical cancer. Each girl vaccinated helps end a long-standing cycle of disease across Africa,” said Martin Morand, Senior Country Manager, Ghana at Gavi. With support from Gavi, over 60 million girls have already been vaccinated worldwide. According to Gavi, for every 1,000 girls vaccinated, 17 future deaths can be prevented.

Ghana’s introduction comes with an advantage: it can learn from Kenya’s past struggles with vaccine hesitancy, especially among parents who initially refused the vaccine due to false myths about infertility and opposition from religious groups like the Catholic Church.

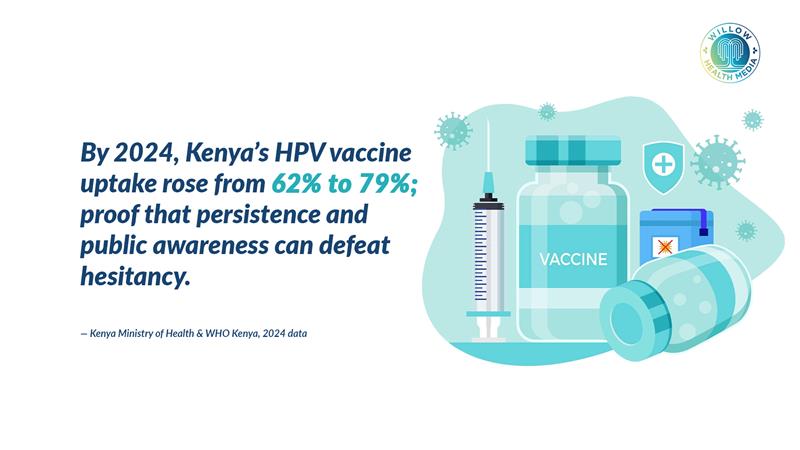

Kenya’s HPV vaccine uptake was low at 62 per cent in 2023. After a year of strong public campaigns, it rose to 79 per cent in 2024, proving that consistent effort can overcome vaccine hesitancy.

Pauline Savai, a cervical cancer survivor and activist, told Willow Health Media that parents who understood the disease’s severity were more willing to vaccinate their daughters. “Having gone through the pain and financial struggle to pay for my treatment, I did not hesitate to take my two daughters for the HPV vaccine as it’s easier to prevent than treat,” she said.

Ghana, Kenya face challenges in poor health-seeking behaviours that impede early detection

In Kenya, researchers report that private and religious schools remain a major hurdle for HPV vaccination. They state that myths and unscientific pronouncements from leaders are causing hesitancy, and this needs to be urgently addressed with more awareness and media campaigns.

Ghana has not yet faced public resistance, but officials know it could happen. Their strategy is to proactively use health workers to address parents’ concerns before opposition can grow.

Both countries face another critical challenge: poor health-seeking behaviours that impede early detection and treatment of cervical cancer. In Kenya, only 16 per cent to 18 per cent of women aged between 25 and 49 years have ever gone for screening, according to the Ministry of Health’s Cervical Cancer Screening, Early Detection, Management and Support Manual. This is despite 75 per cent being aware of the need for testing.

Ghana’s screening rates have not been detailed in available reports, but the country is among 34 African nations that have begun using HPV-DNA screening, a more effective method for detecting and preventing the disease compared with traditional screening methods.

Health officials in both countries stress that the vaccine is essential. It protects girls directly, avoiding the arduous task of getting adult women to come in for screenings.

Kenyan cancer expert Dr Jesse Opakas suggested expanding vaccination to boys

When Kenya launched its HPV program in 2019, it gave the vaccine in two doses, six months apart. The goal was to reach 800,000 ten-year-old girls. However, the WHO recommended a single-dose HPV vaccine during a side event at the third International Conference on Public Health in Africa (CPHIA 2023) in Lusaka, Zambia. This single-dose recommendation makes vaccination easier and faster, helping Africa eliminate cervical cancer sooner by removing the problem of getting girls to return for a second shot.

It is unclear if Ghana is using the newer single-dose vaccine, though the WHO recommendation came before its rollout. Separately, a Kenyan cancer expert, Dr Jesse Opakas, suggested expanding vaccination to boys aged 9-14, as they can also carry and spread HPV.

“Vaccinating them would reduce infection rate and subsequently cervical cancer risk,” said Opakas, a clinical oncologist at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital. He added that HPVs can also cause penile, anal and oral cancers and genital warts, which the HPV vaccine would prevent.

Neither Ghana nor Kenya currently vaccinates boys, focusing instead on girls who face the highest risk of cervical cancer. But Opakas’s remarks suggest a probable future expansion to further cut HPV transmission.

Ghana’s rollout also reflects growing momentum across Africa; by early 2024, 28 countries had introduced the HPV vaccine. In West Africa, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, and Senegal have also joined in with Gavi’s support.

Misinformation spreads fast, especially around vaccines linked to reproductive health

“Every dose of the HPV vaccine brings us closer to a future free from cervical cancer. The vaccine is safe, effective and a true gift of health for generations to come,” said Dr Fiona Braka, WHO Ghana Representative.

Former Health Cabinet Secretary Sicily Kariuki described Kenya’s 2019 introduction as part of the country’s strategy for preventing and reducing the cervical cancer burden. The same rationale drives Ghana’s campaign.

“With UNICEF support, Ghana has secured 2.5 million HPV vaccine doses – enough to protect all eligible girls and potentially prevent around 40,000 deaths caused by cervical cancer,” said Pauliina Mulhovo, UNICEF Representative, OiC.

Ghana begins its HPV vaccination drive with advantages Kenya lacked in 2019. It can learn from Kenya and other African countries’ experiences, anticipate hesitancy, plan better communication, and benefit from the WHO’s simpler single-dose recommendation.

Ultimately, success will depend not just on vaccine supply but on trust, myth-busting

Still, challenges remain. Misinformation spreads fast, especially around vaccines linked to reproductive health. Cultural and religious concerns may arise, and reaching out-of-school girls in remote areas will test Ghana’s outreach efforts.

Kenya’s progress shows that persistence works. Between 2023 and 2024, vaccine uptake rose by 17 percentage points, proving that steady engagement, survivor stories, and clear communication can win trust.

Both countries share a goal: eliminating cervical cancer as a public health threat. With Gavi, UNICEF, and WHO backing, they’re helping save 1.4 million lives by 2025 and empowering girls across Africa.

Ultimately, success will depend not just on vaccine supply but on trust, myth-busting, and consistent coverage. Ghana and Kenya’s journeys offer powerful lessons for Africa’s fight against cervical cancer.

Healing Hands: In cancer treatment & care, science alone is not enough

Brachytherapy nurse Naomi Githaiga shows that cancer treatment helps patients navigate fear, stigma and complex procedures with empathy and care. This story reminds us that in Kenya’s growing cancer burden, healing hands are just as vital as the machines.