Over 1,500 residents depend on one nurse, one bed, and no oxygen supply. Community Health Promoters (CHPs) trek through flooded areas risking snake bites

In Bulwani, a remote settlement in Busia County cut off by Lake Victoria’s backflow since 2020, giving birth has become a deadly gamble. The 1,500 residents depend on a single crumbling health facility with one nurse, one bed, and no oxygen supply.

Bulwani Dispensary serves as the only health centre for residents marooned between Yala Swamp and Lake Victoria. The facility is reachable only by boat – a gruelling one hour and 20 minutes from Mabinju Beach. Many expectant mothers never make it in time. Others deliver on boats “in pain and fear, far from help.”

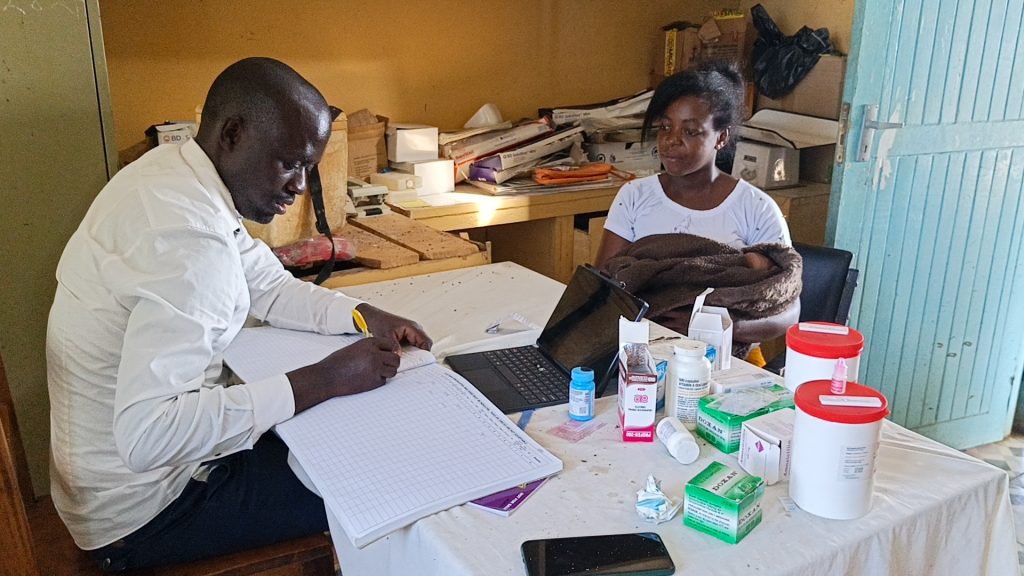

Nicholas Ouma Sikuku, the facility’s only nurse, has worked alone since his colleague died in April 2024, the year 26 women delivered at the facility.

By mid-2025, that number had reached 14. “A woman might be in labour while another patient is convulsing on the bench. Handling that alone is overwhelming,” Sikuku told Willow Health.

Jenipher Ojiambo, delivering her fifth child, described the struggle: “There’s only one [bed]. If we are three women, it becomes a real struggle. The nurse does what he can, but he’s alone. If things get bad, there’s no one else who can help.”

When water levels rise, families erect tents around the dispensary for shelter

She added: “The facility has no oxygen, no backup staff, and a fragile supply of essential drugs. When you’re in labour and there are no medicines, they will send someone across the lake to get them. You’re left waiting in pain, unsure if help will return in time.”

Leonidah Nafula, a mother of five, said emergency referrals require a dangerous hour-long boat journey to Port Victoria Sub County hospital.

Before the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) donated a boat ambulance, transport costs ranged from Ksh1,000 to Ksh3,500, plus Ksh1,000 to Ksh2,000 for the boat operator. Now families contribute Ksh1,500 for fuel.

Flooding compounds the challenge. When water levels rise, families erect tents around the dispensary for shelter, robbing the facility of privacy.

Many people stay trapped in their homes, unable to access care.

Bathsheba Auma, who recently gave birth at the facility, worries about complications: “The journey is costly and dangerous, especially at night. Patients must first cross the lake, then hop on a boda to the hospital. If you are not using the boat ambulance at the dispensary, you will be charged exorbitantly.”

When pregnant women lack transport money, CHPs contribute from own pockets

Community Health Promoters (CHPs) face severe challenges reaching pregnant women. Polycarp Okoch Marabi, a former fisherman serving as a CHP for two years, often treks through flooded areas risking snake bites.

“Sometimes you go to pick a pregnant woman and it’s raining, you get drenched. We have no raincoats, no gumboots. You walk through flooded water and risk being bitten by snakes,” Marabi said.

When pregnant women lack transport money, CHPs contribute from their own pockets. “We pick a woman in labour, but the fuel isn’t there. We chip in what we have, and by the time you’re ferrying her on a canoe or carrying her by yourself, it’s like handling a ticking time bomb,” he said.

Private boat transport now costs Ksh4,000. With the ambulance boat, they charge Ksh1,500 for fuel, “but still, many can’t afford it.”

Caroline Sikudi Odaha, a CHP since 2011, said they started as volunteers and now receive inconsistent stipends. During floods, residents either migrate or get stranded, forcing CHPs to reach them under dangerous conditions.

All passengers on board risk the danger of drowning in case the boat capsizes

Hillary Osae, the volunteer boat operator, faces constant fuel shortages. “Sometimes you have a patient, but no fuel. You go around asking for help. If it’s not available, you’re forced to get it from outside.”

Safety equipment like life jackets are unavailable. “You might be crossing the lake to Port Victoria and then it starts raining in the middle of the lake, with a critical patient on board and no life-saving gear, all the passengers on board risk the danger of drowning in case the boat capsizes or even you can lose the patient on the way,” he said.

Despite working voluntarily, Osae expressed frustration: “But I can’t eat ‘thank you’. You take someone across the lake at night, in the rain, to help them give birth or get treatment. They don’t pay you, they just say thank you. But what do I feed my children with?”

According to the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) 2022, about 88 per cent of births in Busia were delivered by skilled providers, compared to the national average of 89 per cent.

About 71 per cent of women aged 15-49 years with live births attended at least four antenatal care visits. The fertility rate stands at 3.7 compared to the national average of 3.4. Postnatal care coverage remains high, with 91 per cent of women receiving checkups within two days after delivery and 92 per cent of newborns receiving postnatal checks within the same timeframe. Among children aged 12-23 months, 82 per cent were fully vaccinated.

Dr Lusamba Wilberforce describes maternal health in Bunyala as “a tale of two realities”

Mortality rates show gradual improvement. Neonatal mortality stands at 22 deaths per 1,000 live births, infant mortality at 34 deaths per 1,000 live births, and under-five mortality at 53 deaths per 1,000 live births – improving from 21, 32, and 41 deaths respectively in the 2014 KDHS survey.

Kenya’s institutional Maternal Mortality Ratio (iMMR) was about 99 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2021, according to District Health Information Software data.

A study found 1,162 maternal deaths and 1,174,774 live births in health facilities that year, with rural and flood-prone areas experiencing much higher maternal mortality rates.

Dr Lusamba Wilberforce, Chief Officer for Medical Services and Universal Health Coverage in Busia County, describes maternal health in Bunyala Sub-county as “a tale of two realities.”

“Bunyala is very unique. On the northern and western sides, people are not affected much by floods and the backflow from Lake Victoria. But the southern and central areas suffer most during flooding. Accessing care becomes nearly impossible,” he said.

Substantial renovations are ongoing at Port Victoria Hospital, including a new maternity wing, theatre, X-ray unit, and ultrasound machine – the first in over a decade. However, southern outposts like Bulwani remain isolated and critically understaffed.

Poor mobile networks hindering telemedicine besides chronic underfunding

“In Bulwani, there’s only one nurse. Staffing is a challenge,” Dr Lusamba said. Officials have written to the County Public Service Board and County Human Resource Advisory Committee seeking approval for locum staff as a short-term solution.

He acknowledged boat ambulances have increased referrals but fuel costs continue derailing emergency response: “Getting fuel is a big problem. Patients shouldn’t have to dig into their own pockets for emergency care – that’s a right.”

Governor Paul Otuoma recently signed the Facility Improvement Fund (FIF) Bill into law, allowing money generated at facilities to remain there. “This will make it easier for Bulwani to allocate funds for fuel and other urgent needs,” Dr Lusamba said.

Major challenges remain, including poor mobile networks hindering telemedicine and chronic underfunding. “Busia County has a deficit of 200 nurses who left but weren’t replaced. We required Ksh2 billion for the health department, but were only given Ksh1.6 billion.”

The county plans to send a team to Bulwani next month to assess needs ahead of the 2025/26 budget reading. “We need another boat and more skilled personnel, and that’s our focus for the new fiscal year,” Dr Lusamba said, adding “We’re in talks with Safaricom to boost internet connectivity. And once we sort the backflow issue, it will be easier to move between areas.”