This is the question emerging among urban women, particularly those with access to genetic testing…

It began as a tiny lump the size of a groundnut, barely noticeable beneath the skin of her left breast. She found it by accident one evening while dressing for bed. There was no pain, no redness, no urgency. Just a silent voice in her head whispering, “Maybe it’s nothing.”

Three months passed. The lump grew. Slowly and subtly. Her left nipple began to pull inward, a retraction she ignored, blaming it on her bra. Then came the discharge: clear at first, then tinged with blood. Still, she told no one. Life was too busy, money was tight, and the fear of hearing the word cancer kept her away from the hospital.

By the sixth month, she was sleeping on one side to avoid the pain. Her breast had changed shape. Her armpit felt tender. At nine months, the pain began waking her up at night—sharp, electric pain that pulsed through her chest like a warning siren.

At month 12, she finally walked into the clinic.

What should have been an early-stage, manageable diagnosis had now progressed. The delay, the denial, and the misinformation had taken their toll not just on her body, but on her odds of survival.

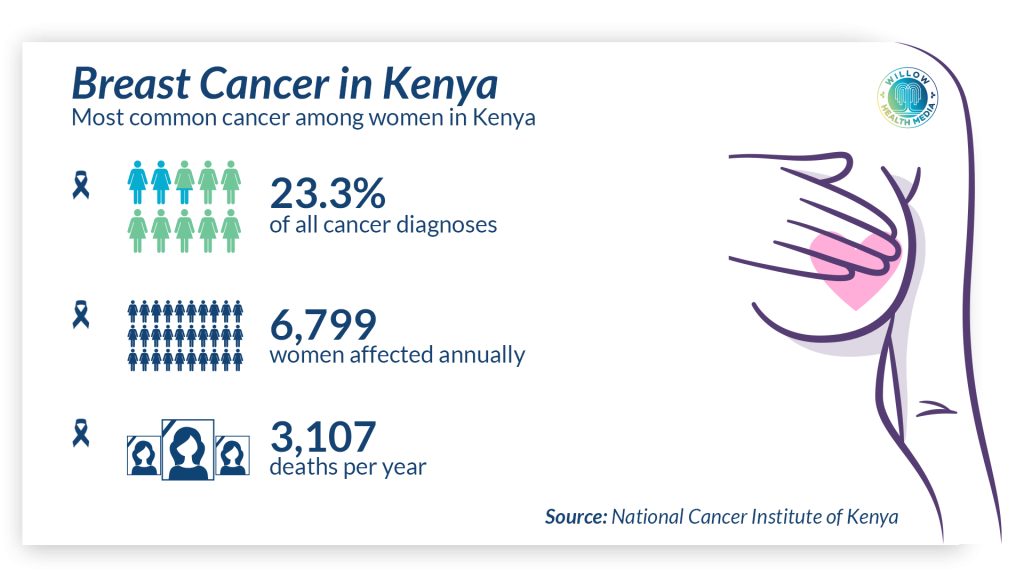

In Kenya, this is not an uncommon story.

Fear leads many women to delay screening or panic unnecessarily

One of the commonest misconceptions about breast health is the belief that every lump is cancer. This fear, while understandable, leads many women to delay screening or panic unnecessarily before diagnosis.

In reality, most breast lumps are benign, especially among younger women. Common non-cancerous causes include cysts, fibroadenomas, and breast infections.

According to data from the American Cancer Society and World Health Organization (WHO), up to 80 per cent of breast lumps in women under 40 are non-cancerous. These benign masses often require monitoring rather than immediate intervention.

For women under 35 years, breast ultrasound is the preferred initial tool as it can clearly distinguish between solid and fluid-filled lumps.

For women over 40 years, mammography is the gold standard, especially for detecting small, dense, or calcified lesions.

Breast cancer is one of the few cancers where early detection makes a measurable difference in survival. When caught at Stage I, the five-year survival rate can exceed 95 per cent, thanks to advances in imaging, surgery, and targeted therapies.

In the fight against breast cancer, genes carry a heavy weight

Globally, the WHO reports that breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women, surpassing even lung and cervical cancers. Yet, when identified early through routine screening, mortality rates can be cut by up to 40 per cent.

In Kenya, the picture is more sobering. According to data from the Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) and the Ministry of Health, about one in four breast cancer patients present at Stage III or IV, when treatment becomes more complex, expensive, and the chances of survival drop dramatically. Late presentation is often due to fear, lack of access and myths surrounding diagnosis.

In the fight against breast cancer, one word carries heavy weight: genes.

Mutations in two specific genes—BRCA1 and BRCA2—are known to significantly increase a person’s risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer. These mutations impair the body’s natural ability to repair damaged DNA, making cancer more likely to develop.

However, despite growing public attention, the reality is more reassuring: genetic mutations account for only five–10 per cent of all breast cancer cases. That means the vast majority of patients do not have a hereditary form of the disease.

Risk of cancer shaped by genetic, hormonal, environmental, lifestyle factors

Women with a strong family history, particularly if a mother, sister, or daughter had breast cancer before menopause, are advised to begin screening as early as age 25 to 30. In such cases, genetic counselling and testing for BRCA mutations may be recommended.

If a BRCA mutation is confirmed, high-risk individuals may consider enhanced surveillance or, in rare cases, risk-reducing mastectomy. This is preventive surgery, not a treatment, and it’s a deeply personal decision made in consultation with specialists.

Understanding your family history is an important step. But so is knowing that having a gene is not a sentence, and not having one is not immunity. Personal risk is shaped by many factors: genetic, hormonal, environmental and lifestyle.

Sporadic breast cancer accounts for over 85–90 per cent of all breast cancer cases globally. It arises from a complex mix of factors that are not inherited genes, but rather lifestyle, hormonal exposure and age-related risks.

The most common non-genetic risk factors include late or no childbirth, early menstruation (before age 12) or late menopause (after age 55), obesity especially after menopause, regular alcohol consumption and prolonged use of hormone replacement therapy.

Should you remove a healthy breast to avoid a future diagnosis?

All of these can increase lifetime oestrogen exposure, which fuels the development of certain types of breast cancer, particularly oestrogen receptor-positive (ER+) tumours.

In 2013, Hollywood actress Angelina Jolie made global headlines after revealing she had undergone a preventive double mastectomy. She carried the BRCA1 gene mutation, which gave her an estimated 87 per cent lifetime risk of developing breast cancer. Her decision sparked what is now known as the “Angelina Jolie effect” a worldwide surge in awareness and interest in prophylactic mastectomy.

Kenya, too, is seeing a shift.

Among urban women —particularly those with access to genetic testing —the question is emerging: “Should I remove a healthy breast to avoid a future diagnosis?” For BRCA-positive women with a strong family history, preventive mastectomy is no longer taboo, but part of a difficult, data-driven dialogue.

Still, it remains a deeply personal and ethically layered decision. Should someone undergo major surgery when no cancer exists? What does it mean for identity, femininity, and emotional well-being, especially in African cultures where breasts carry both maternal and symbolic meaning?

Globally, studies show that preventive mastectomy can reduce breast cancer risk by up to 95 per cent in BRCA-positive women, but it is not the only option. Enhanced surveillance, hormonal risk-reduction therapy and lifestyle changes are all part of the toolkit.

Early screening remains the critical gap between knowing and acting

The dilemma remains, ‘cut before cancer comes’ or ‘monitor closely and live with uncertainty?’

In Kenya, where access to consistent imaging and specialist care is uneven, this question weighs even heavier on the shoulders of women trying to choose between fear and freedom.

While breast cancer awareness has grown across Kenya, early screening remains the critical gap between knowing and acting.

Across the country, non-profit organisations have stepped in to bridge the awareness and access gap. The Faraja Cancer Support Trust, for instance, offers free screening, counselling, and patient navigation services in partnership with public and private hospitals. The Kenya Cancer Association runs mobile breast health clinics and targeted campaigns in underserved counties

Access remains uneven. While clinical breast exams and ultrasounds are relatively low-cost (Ksh500–1,500 in most public facilities), mammograms remain unaffordable for many, ranging from Ksh2,500–7,000 in private clinics.

Public hospitals like KNH, Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) and some county referral hospitals offer subsidised or free mammograms during national awareness months. Still, many rural women must travel long distances or wait months for appointments.

To save more lives, Kenya must invest not only in machines and medics, but in trust-building, follow-up systems, and community outreach that make screening routine, not a luxury or a last resort.

This story was first published by Willow Health Media on August 1, 2025.