I drink an entire bottle of whisky in one sitting while others manage a few beers. Now I have gastritis, Joshua Omondi, clinical officer

Joshua Omondi, a clinical officer in Nairobi, began drinking alcohol casually at 18, but it has since become destructive.

“I’ve been drinking for four days consecutively this week,” says the 31-year-old. “Now I feel this pain in my gut—it is from the gastritis I contracted last year. I drink an entire bottle of whisky in one sitting while others manage a few beers.”

In Kenya, many start drinking out of peer group pressure, social bonding, harmless habit, or as a coping mechanism against stress and challenges of life, while others are functional alcoholics- they drink but manage their affairs just fine. However, Omondi’s case tells a different story.

“When I get drunk the night before work, I end up sweating buckets during the day. I am weak, and I don’t want to talk to anyone. It takes time before I am completely back to normal, so even working isn’t at 100 per cent.”

This cycle, often called “kutoa lock”—drinking again to relieve hangover symptoms—exemplifies dependency.

“I wake up shaking and weak. Drinking a quarter bottle of whisky makes me feel normal again, but by evening, I am drinking again,” says Omondi who previously could have been described as an ‘alcoholic.’

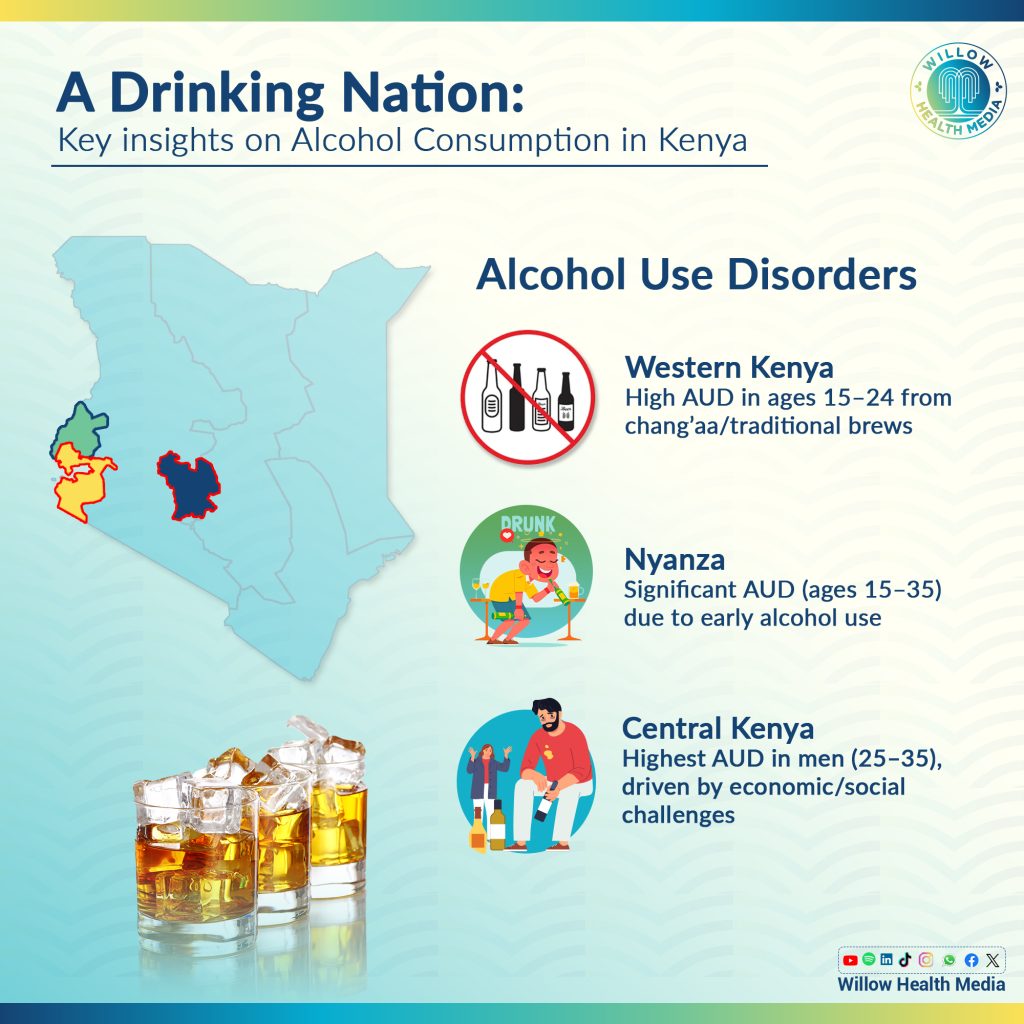

Indeed, alcoholism has long been used to describe excessive drinking, but in 1994, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) moved away from that term and adopted Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) in 2013 to describe a chronic, progressive brain disease.

Having AUD is thus not a lack of willpower or personal failure—it’s a medical condition requiring treatment.

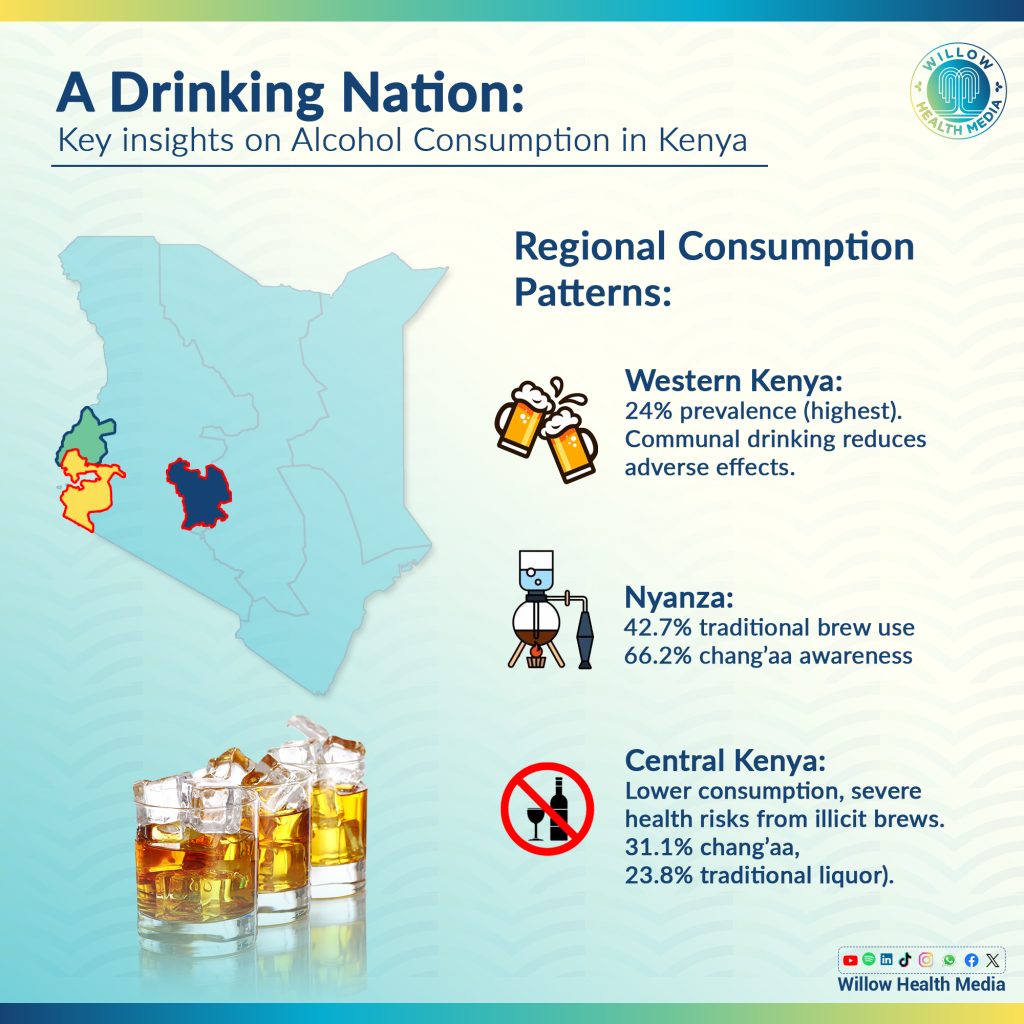

According to the 2022 NACADA Survey, 11.8 per cent of Kenyans aged 15–65 consume alcohol regularly- of which 10 per cent struggle with AUD.

Men bear the brunt, with 20.4 per cent reporting alcohol use compared to 6.3 per cent of women.

The NACADA Survey notes that men are likely to suffer from AUD, with 15.7 per cent affected, compared to just 4.6 per cent of women. Omondi thus suffers from AUD which remains downplayed and misunderstood.

Psychologist Isaac Maweu explains that men cope with alcohol to manage stress but “this reliance creates a vicious cycle that worsens over time.”

The financial and social costs of alcohol are staggering. Omondi admits to spending Ksh20,000 in one week on alcohol, a significant portion of his income. “It’s not just the money—it’s the waste of my time and energy,” he adds.

Another regular swallower, Joshua Juma, 31, concurs that the financial strain is severe as “I’ve spent Ksh6,000 in one night, half my rent, just drinking and buying others.”

Juma, an online freelancer, has faced theft, risky unprotected sex and violence in bar brawls because of his drinking and soberly concludes, “Alcohol wastes your money and your life. It is God’s grace I haven’t contracted HIV.”

Both Juma and Omondi struggle with social norms that reinforce alcohol use.

“My friends are drinking buddies,” Juma explains. “Whenever we meet, there has to be alcohol, or something is missing without it.” Omondi echoes this sentiment as “There’s nothing to talk about where we’re sober, but when drunk, stories just flow.”

Clinical Psychologist Mwari Muthaura explains that Kenyan men “feel they can’t express weakness, so they turn to alcohol. It doesn’t fix the problem—it amplifies it.”

She continues: “I’ve seen clients start the day with a shot just to make it through. It is not about enjoying a drink; but numbing overwhelming feelings of anxiety, depression or hopelessness. And more alarmingly, it’s starting as early as 14.”

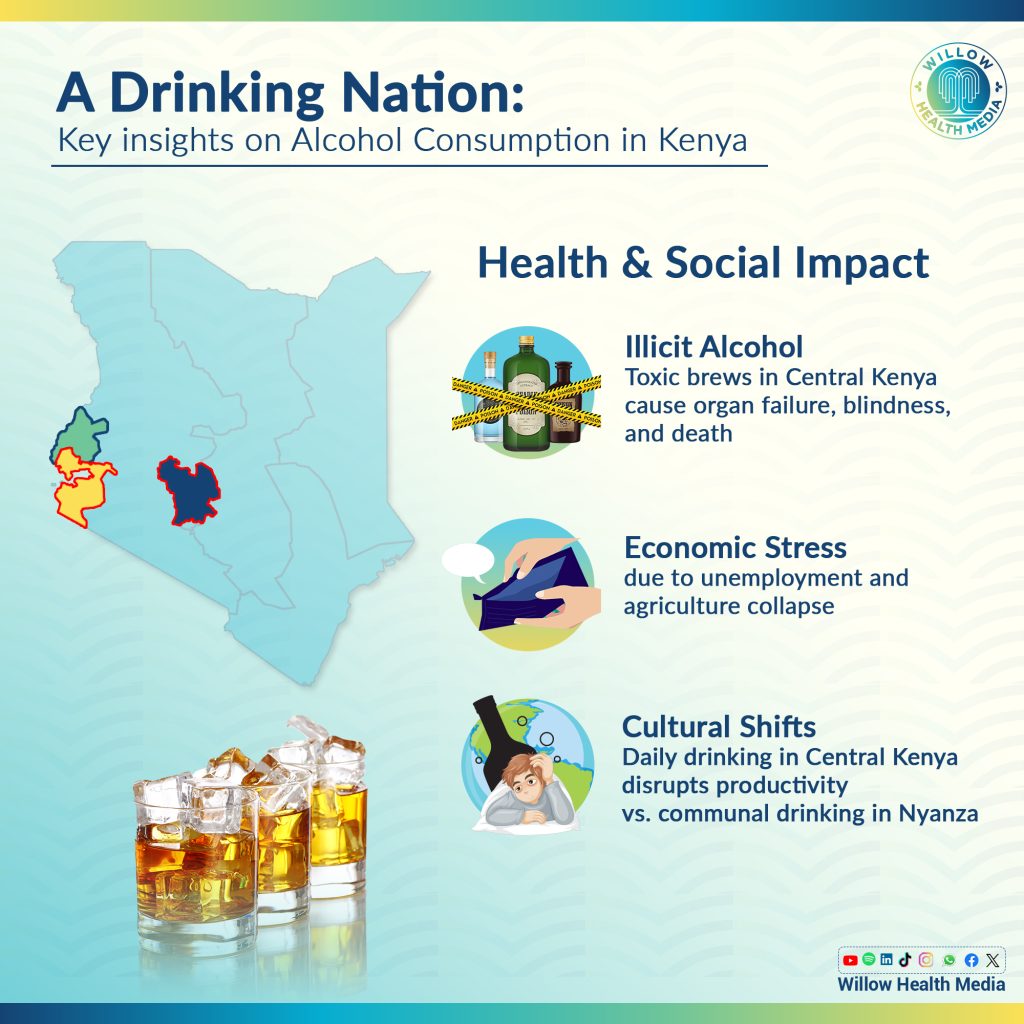

Omondi singles out the availability of cheap alcohol and environmental factors like the saturation of bars in most city estates, like the Sunton area of Kasarani in Nairobi which has “bars everywhere. If I had something to keep me busy, it would be easier to quit.”

AUD also wreaks havoc on the body and mind as heavy drinking is linked to liver disease, pancreatitis, cancer, and other severe conditions.

Omondi’s hospitalisation after a week of heavy drinking highlights the physical toll. “I was on an IV (intravenous (IV) fluid therapy) for two days. The pain was unbearable, but even after that, I went back to tasting alcohol.”

Psychologically, alcohol rewires the brain, making it harder to manage stress and emotions. It often worsens anxiety and depression.

According to NACADA, those who drink 2.3 times or more are more likely to suffer from depressive disorders than non-drinkers.

The Functional Alcoholics who may hold down jobs, maintain relationships, and meet daily obligations—are not spared either.

“You often hear people say, ‘I can stop whenever I want,’ or ‘I don’t drink that much,’ but that’s denial,” Mwari explains.

She adds: “Alcohol is one of the most common forms of self-medication. People drink to forget, to sleep, to block out their thoughts. But the sleep isn’t restful, and the problems are still there when they wake up. In fact, they’re worse.”

Both Juma and Omondi recently took the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), scoring 25 and 27, respectively.

The AUDIT, a screening tool by the World Health Organization (WHO), measures alcohol-related risks and disorders. A score of 20 or above signals alcohol dependence. For Omondi, the results were sobering: “I know I am not okay. Things are bad, and I need to control this.”

However, Juma says “Visiting a hospital isn’t an option for me right now,” reflecting a broader cultural tendency to downplay AUD as a personal failing rather than a medical condition.

AUD affects 10 per cent of Kenyans, yet it remains stigmatised and underdiagnosed, and recovery begins with recognizing the problem and seeking help. As Juma reflects, “I have wanted to quit for a long time. It is not easy, but I know I must try.”

But recognizing the signs early is crucial. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), two or more of the following symptoms in the past year signal AUD:

- Drinking more or for longer than you planned.

- Unsuccessful attempts to cut down or stop drinking.

- Strong cravings for alcohol.

- Spending a lot of time drinking or recovering from drinking.

- Letting drinking interfere with responsibilities at work, school, or home.

- Continuing to drink even though it’s causing trouble in relationships.

- Needing more alcohol to get the same effect (tolerance).

- Experiencing withdrawal symptoms, such as shakiness, sweating, or nausea, when trying to quit.

“Having two or more of these symptoms could signal an alcohol use disorder,” explains Mwari. “But kidney disease, hallucinations, or severe liver damage are common wake-up calls.”

Breaking free from AUD is difficult but possible. For Omondi, the first step is setting limits, “to drink only once a week,” but better treatment options for AUD include:

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) to address thought patterns driving drinking.

- Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) to build commitment to quitting.

- Support groups like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA).

- Inpatient rehabilitation for severe cases.

As Maweu concludes: “When men come to therapy, it’s often after things have completely fallen apart—work issues, family crises, or severe health problems. That delay makes recovery even harder.”

This story was first published by Willow Health Media on December 27, 2024.