Unlicensed clinics thrive when people lack access to proper care or can’t afford it. For Amos Isoka, a Ksh1,000 tooth extraction by a quack ended in fatal respiratory failure.

On New Year’s Day, Amos Isoka, a Kenyan in his 20s, paid Ksh1,000 for a tooth extraction at Life Clinic in Kawangware, a low-income residential area 15 kilometres West of Nairobi CBD.

But shortly after the procedure, Isoka’s neck, tongue and chest swelled, prompting an emergency evacuation to Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH).

Despite two surgeries at KNH, Isoka died from a fatal respiratory failure. An autopsy report from Dr Joseph Ndung’u indicated that the unqualified practitioner who extracted his tooth failed to sanitise Isoka’s infected jaw.

According to Dr Ndung’u, the quack’s decision to extract the tooth without sanitising the mouth caused the infection to enter the jaw, spread to the neck, armpits and chest, subsequently blocking Isoka’s airway.

The Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists’ Council (KMPDC) closed the facility alongside Jamii Medical Centre, another unlicensed facility that was illegally offering dental services in Kawangware.

What fuels unlicensed dental clinics? Well, the World Dental Federation (FDI) 2025 survey findings singled out limited access to qualified dental care, economic hardships and the lure of lower costs as major reasons.

Globally, 58 per cent of National Dentists Associations reported cases of patient harm by unlicensed providers, calling for stronger safeguard policies.

Dr Timothy Theuri, the former CEO of Kenya Health Federation, reckons that “Amos was failed by the system-a collection of organisations, state agencies, people operating the system and the culture of Kenyans.”

Dr Theuri, a former president of the Kenya Dental Association (KDA) was speaking during an X Space session titled, Healthcare or Gamble? The cost of a broken healthcare system in Kenya, organised by K24 Digital and hosted by Priscilla Wahiu on January 29, 2026.

“Someone opened a kibanda (kiosk), started treating people, and the outcome was deadly,” said Dr Theuri. “This happened because KMPDC, which acts as the healthcare police, didn’t have people on the ground.”

He attributed KMPDC’s failure in Isoka’s case to staff shortages and budget constraints.

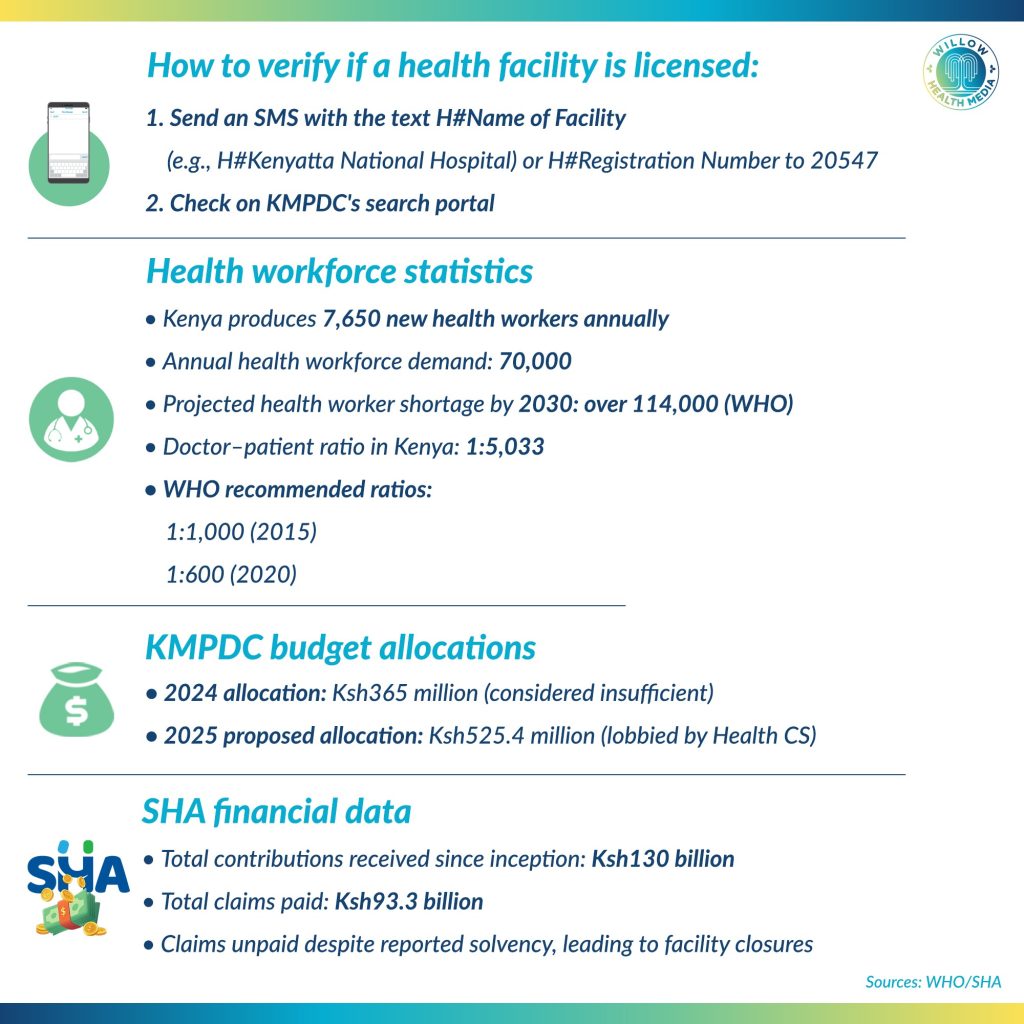

In 2024, KMPDC, the semi-autonomous government agency, was allocated Ksh365 million, which was deemed insufficient.

In 2025, Health Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale lobbied for an increased allocation of Ksh525.4 million to enable the agency to conduct inspection and enforcement mandates effectively.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), Kenya produces 7,650 new health workers annually against a demand of 70,000. The agency projected the shortage to grow to over 114,000 in 2030 if training and hiring rates are not increased.

According to KMPDC, Kenya has a doctor-patient ratio of 1: 5033 far below the WHO-recommended ratio of 1:1000 in 2015 and 1:600 in 2020.

In an earlier interview with Willow Health Media, David Kariuki, CEO, KMPDC, cited inadequate human resources and failure to ensure patient security among the reasons for the closure of over 900 health facilities in 2025.

During an X Space event, Dr Theuri urged the public to help ensure only licensed facilities and certified personnel treat patients. He admitted this might not be possible in an emergency.

In the X Space held a day after the Social Health Authority (SHA) was accused of losing Ksh11 billion, most participants said the health scheme had failed Kenyans.

Anthony Muriithi, a good governance advocate, questioned the urgency for transitioning from the National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) to the SHA.

“This system opened more fraud avenues. Was it meant to provide health for all Kenyans or wealth for some Kenyans? It should have been easier to build on what was working in NHIF,” Muriithi observed.

Bernard Kiprop, a data enthusiast, argued that the system’s failure was facilitating malpractice, a scenario that cost Isoka’s life.

“When public facilities lack personnel or equipment, quacks will thrive. Other medics in public facilities prioritise their private clinics over public service take advantage of the gap. This opens doors for health insurance fraud, too,” said Kiprop.

Bundi Kirianki, a policy and governance expert, said the government had lost its steps in implementing SHA as “The healthcare system can only be termed effective when it serves all, not some Kenyans,” said Kirianki. “The statistics on paper aren’t representative of true situations on the ground.”

Dr Theuri agreed that some gaps in SHA needed urgent revamps to serve all Kenyans effectively, and “A digital system with end-to-end visibility of claims should show who was paid the Ksh11 billion,” he said. “Blanket statements demonising private health facilities aren’t a solution.”

Duale clarified that the Ksh11 billion was not a loss, but unclaimed fees that SHA had flagged as ‘suspicious.’ He indicated that since inception, SHA had received Ksh130 billion in contributions and disbursed Ksh93.3 billion in claims.

This shows the fund is solvent (sustainable), though the situation on the ground contradicts the statistics, as many facilities are closing down due to unpaid claims.

Oduor Otieno, Vice Chair of the Kenya Health Federation’s Health Regulation Committee, doubted the SHA’s sustainability as “There are so many medical bill fundraisers, indicating gaps in our healthcare system”, and a functional system should manage to detect errant aspects like fraud, quacks and unlicensed facilities.

“SHA has financing model failures. It’s suitable for high-income countries,” inferred Otieno. “It is a broken system that needs a reboot.”

Participants in the X-Space questioned why SHA was struggling financially despite charging higher premiums compared to NHIF. Kiprop reckoned registered members were contributing, “But the government is failing to remit, discouraging people from willingly paying premiums because they can’t access services.”

Dr Theuri put the government on the spot for massive failures in primary healthcare coverage as “State-funded programs like primary healthcare are performing at 20 per cent. Dialysis and oncology are doing much better.”

Dr Theuri was of the opinion that teachers’ and police health covers, which made losses under NHIF, should not be incorporated into SHA.

An Eldoret resident, Tito Kimutai, urged the government to copy the Inua Jamii program, which gives cash to seniors every two months, for the SHA. He said the government should have set up the SHA before Inua Jamii, and could have used similar methods to register and cover the needy.

Participants agreed that Kenya can only reach its development goals with an efficient healthcare system, as “A healthy nation drives a working nation, which in turn generates money to support healthcare coverage for indigents,” observed Kimutai.

Participants all called for the SHA to pay claims on time to prevent facilities from shutting down due to a lack of funds. They said the closure of licensed clinics is driving people toward unlicensed quacks.

Kimutai added that public confusion about SHA’s services is damaging its reputation and creating opportunities for fraud.

“To reduce fraud, wastage and abuse of SHA, we need clear mechanisms to ensure the right beneficiaries get the right benefits. We also need to introduce a waiting period like NHIF to motivate timely paying of premiums,” Dr Theuri proposed.

The stakeholders agreed that simplifying means testing tools and having standardised premiums would attract more contributions and sustain the revolving pool.

“Collusion between providers and receivers should be frowned upon,” said Dr Theuri. “SHA shouldn’t be happy to pay for transplants and surgeries but won’t make billboards urging Kenyans to eat and live healthily.”

Graphics by Arthur Mbuguah.