A common reason given for excluding students in Kenyan schools is “architectural barriers.” Many top schools, built in the colonial period, have features like multiple floors, narrow hallways, and toilets hard to use for those with disabilities.

A profound national debate on accessibility in Kenyan education defined the start of the 2026 academic year. While “reporting day” is a milestone for most, the recent incident at a top national school where a learner with disabilities was allegedly denied admission due to “capacity constraints” has exposed a systemic fracture.

This event serves as a critical case study in the tension between institutional readiness and the statutory mandates of the Constitution of Kenya and the Persons with Disabilities (PWD) Act 2025.

As the Ministry of Education faces mounting pressure to address these disparities, the focus has shifted toward the two primary pillars of inclusive education in Kenya: the Kenya Institute of Special Education (KISE) and the corporate-led Niko Fiti Initiative. The core issue suggests the legal, social, and infrastructural landscape of inclusive education has little to do with “capacity” as a barrier; rather, institutional will is the actual bottleneck.

In January 2026, the gates of Lenana School became the site of a viral national heartbreak. A young boy, having secured a placement through merit in the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE), arrived to find his path blocked not by his grades, but by his wheelchair. The administration cited a lack of “physical capacity” to accommodate orthopaedic disabilities, sparking debate over the definition of a “National School.”

In the Kenyan context, a National School is more than an educational centre; it is a symbol of unity and meritocracy. When such an institution claims it cannot accommodate a qualifying student, it sends a message that excellence is reserved for the able-bodied. This incident did not occur in a vacuum; it follows decades of integration efforts that have often focused on “placing” children in schools without “supporting” them once they arrive.

When a learner with a disability is identified, they undergo a Functional Assessment

Inclusive education is not merely a matter of physical placement; it is a clinical and pedagogical process overseen by KISE. As the national body responsible for training special needs educators and assessing learners, KISE operates through a network of Educational Assessment and Resource Centres (EARCs).

When a learner with a disability is identified, they undergo a Functional Assessment at an EARC. Unlike a standard medical diagnosis, this assessment creates an educational roadmap. It determines the specific “Reasonable Accommodations” a student requires. These may include:

- Assistive Technologies: Braille embossers, screen readers, or hearing aids.

- Environmental Modifications: Ground-floor classroom placement or specialised desks.

- Curriculum Adaptation: Tailoring the Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC) to meet sensory needs.

When KISE recommends a learner for a mainstream national school, they affirm that the student possesses the intellectual and functional capacity to thrive in that environment. Therefore, an institution’s refusal to admit such a student is not merely a rejection of an individual; it is a rejection of the State’s own technical validation process.

A recurring defence for exclusion in Kenyan schools is the “architectural barrier.” Many of Kenya’s premier institutions, constructed during the colonial era, feature multi-story masonry, narrow corridors, and inaccessible sanitation facilities.

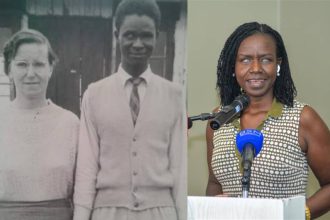

A notable precedent is Nicodemus Kilunda who was successfully integrated into Lenana School

The Niko Fiti-Ability Beyond Disability program, a flagship initiative by the Kenya Reinsurance Corporation (Kenya Re), was designed specifically to dismantle this defence.

For over a decade, Niko Fiti has operated on the philosophy that disability is not an inability, but a mismatch between a person’s needs and their environment. The program has transformed schools by:

- Providing Hardware: Distributing high-quality mobility devices, including specialised wheelchairs and tricycles, to ensure students can navigate vast school compounds.

- Structural Modification: Funding the construction of ramps, the widening of doorways, and the modification of dormitories.

- Psychological Shift: By showcasing success stories of students who have excelled in these modified environments, the program challenges the “stigma of burden” that many head teachers harbour.

A notable historical precedent is the story of Nicodemus Kilunda. Through the support of Niko Fiti, Kilunda successfully integrated into Lenana School years ago, proving that with the right modifications, the “capacity” of the school is infinite. The 2026 outcry, therefore, represents a regression in institutional memory rather than a new challenge.

The legal framework in Kenya is unambiguous. Article 54 of the Constitution states that a person with any disability is entitled to access educational institutions and facilities that are integrated into society. Furthermore, the Persons with Disabilities Act 2025 has introduced stringent penalties for discriminatory practices. Under this law:

- Compulsory Admission: No school, whether public or private, may deny admission to a learner based on disability if they meet the academic requirements.

- Budgetary Allocation: Schools are required to allocate a percentage of their operational funds toward “Reasonable Accommodation.”

- Reporting: School boards must provide annual reports to the National Council for Persons with Disabilities (NCPWD) regarding their inclusivity metrics.

While the Lenana incident highlighted a failure of institutional will, a parallel narrative of success emerged across the country. In several counties, placement centres reported scenes of “relief and joy” as affected learners were embraced by proactive school administrations.

Students with and without disabilities share dining halls, clubs, sit for the same examinations

In these “Inclusion Hubs,” school leadership has moved beyond the “Special Unit” model-where students with disabilities are kept in a separate wing-to a “Fully Integrated” model. Here, students with and without disabilities share the same dining halls, participate in the same extracurricular clubs, and sit for the same examinations. This model has been shown to improve the social-emotional intelligence of able-bodied students while boosting the academic outcomes of learners with disabilities.

The Kenya Institute of Special Education (KISE) plays a pivotal role in monitoring these transitions. By acting as an oversight body, KISE ensures that the “Special Needs” designation is not used to sideline students into substandard vocational paths when they have the aptitude for academic excellence. Their role in the 2026 intake has been to advocate for the Individualised Education Program (IEP), ensuring that every child admitted into a mainstream school has a personalised support plan.

To ensure that the 2026 outcry leads to permanent reform, Kenya must move from reactive crisis management to proactive policy enforcement. The following strategic actions are recommended:

A. Mandatory Accessibility Audits

The Ministry of Education, in partnership with KISE, must conduct mandatory audits of all National and Extra-County schools. Any institution that fails to meet basic accessibility standards (ramps, accessible toilets, and ground-floor dormitory access) should be ineligible for government development grants until it complies.

B. Scaling the Niko Fiti Model

The success of private-public partnerships like Niko Fiti should be scaled. Corporate tax incentives should be offered to companies that invest in the physical modification of public school infrastructure.

C. Teacher Professional Development

The Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC) requires teachers to be facilitators for diverse learners. Teacher training colleges must make Special Needs Education (SNE) a core unit for all graduating teachers, not just those specialising in “Special Education.”

D. Enforcement of the PWD Act 2025

The Ministry must establish a hotline for parents to report admission denials. When a school claims a lack of capacity, the Ministry should immediately deploy a KISE assessment team to evaluate the validity of the claim and, if necessary, provide the emergency funding or equipment needed to facilitate admission.

The narrative of inclusive education in Kenya is at a crossroads. The boy at the Lenana gate did not just want a seat in a classroom; he wanted his right to belong to the future of his country. As Kenya matures as a democracy, the measure of our “National Schools” will no longer be determined solely by their mean scores, but by the breadth of their inclusivity.

Capacity is not a fixed architectural constraint; it is a dynamic expression of a nation’s commitment to its most vulnerable citizens. When KISE provides the assessment, and initiatives like Niko Fiti provide the hardware, the only remaining barrier is the heart of the educator. It is time for the gates to open for every child.

Dr Madeline Iseren is a pharmacist who writes on topical health and medical issues.