Limping to traditional healers feeds a silent epidemic claiming 4,000 lives and leaving 7,000 people paralysed or permanently disabled each year, with men bearing the brunt of the snakebite burden, according to new research.

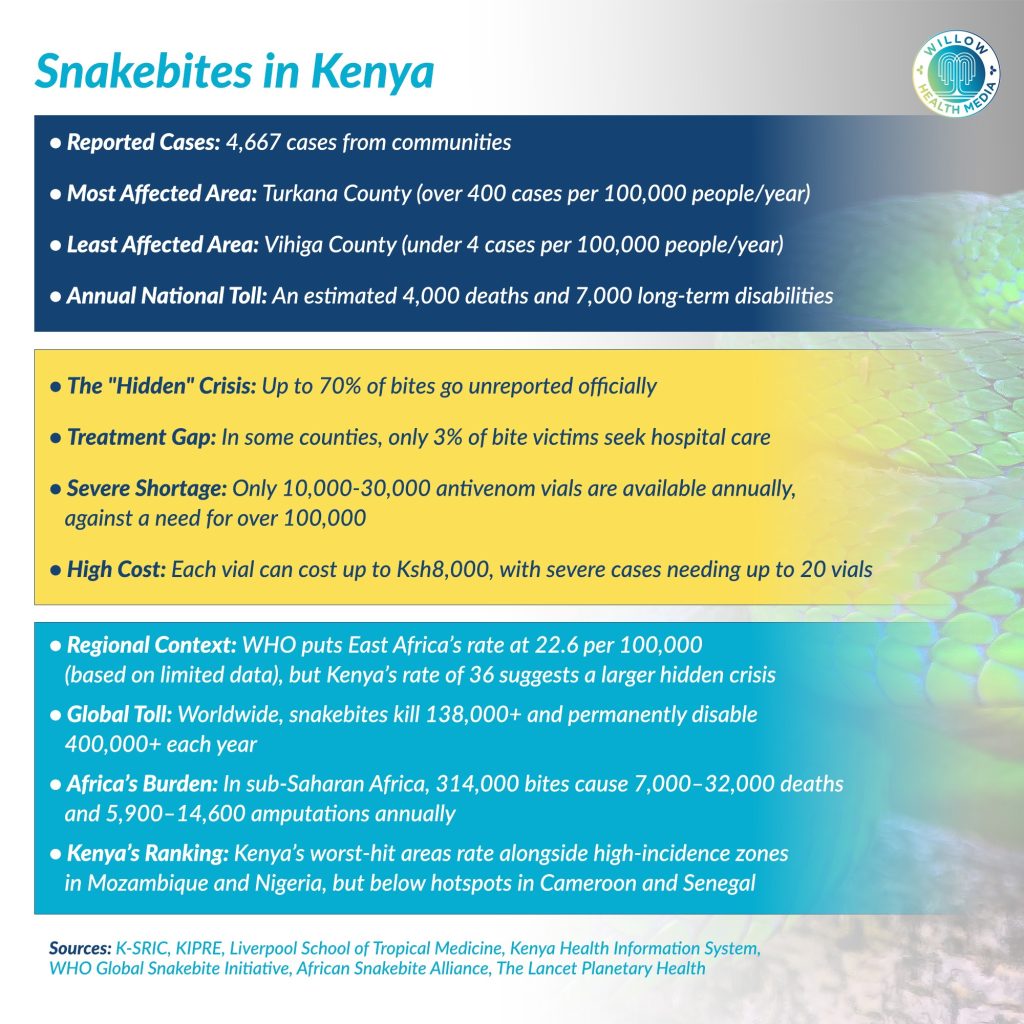

In Turkana County, northwestern Kenya, snakebite is a constant, deadly reality. New research shows that more than 400 out of every 100,000 people are bitten each year- an incidence so high it rivals the world’s most snake-afflicted regions in West Africa.

Just 300 kilometres south in Vihiga County, the picture is dramatically different. There, fewer than four people per 100,000 are bitten each year. This 100-fold gap in risk within a single country has now been mapped in unprecedented detail through an innovative survey that reached more than 13 million Kenyans, about 28 per cent of the population.

The study, led by Dr George Oluoch of the Kenya Snakebite Research and Intervention Centre (K-SRIC) and Prof Ymkje Stienstra of Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, uncovered 4,667 snakebite cases across 17 counties between July 2022 and August 2023.

It was published in the PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases journal in November 2025 and Dr Oluoch reckons it is “the first survey of its scale to systematically capture snakebite incidence across a broad cross-section of Kenyan communities.”

K-SRIC is domiciled within the Kenya Institute of Primate Research (KIPRE).

According to K-SRIC, snakebites in Kenya cause about 4,000 deaths and 7,000 cases of paralysis or major complications annually. However, this likely represents a fraction of the true crisis as up to 70 per cent of all snakebite incidents go unreported, presenting a fundamental problem in tracking snakebite as a neglected tropical disease, notes the study.

Men in rural Kenya perform outdoor occupations that increase snake exposure

Kenya’s northwest bears the heaviest burden. Turkana and Baringo counties top the list with incidence rates exceeding 410 cases per 100,000 people annually. West Pokot follows at 176 per 100,000. The highest-risk areas tend to be sparsely populated rural regions where people live closest to snake habitats and farthest from emergency medical care.

Men face a slightly higher risk overall, with incidence rates of 39.3 per 100,000 compared to 32.2 for women, because men in rural Kenya are more likely to perform outdoor occupations that increase snake exposure. Adults over 15 experience rates nearly four times higher than young children (19.5 versus 5.6 per 100,000), likely reflecting occupational exposure through farming and herding.

In Trans Nzoia County, only three per cent of snakebite victims reported seeking care at a health facility. Even in counties with better healthcare access, 11 of the 17 surveyed counties saw fewer than 70 per cent of victims seeking formal medical care. More than half of all snakebite victims in Kenya seek help from traditional healers rather than hospitals.

The barriers to treatment are both physical and financial. Antivenoms cost up to Ksh8,000 (about $62) per vial, and some patients require as many as 20 doses. Such expenses, exceeding Ksh156,000 ($1,200), are out of reach for rural families relying on subsistence farming or herding. According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), agricultural wage workers in Kenya, including unskilled labourers and herders, earn between Ksh6,500 and Ksh14,500 monthly. Farm owners, on the other hand, earn from about Ksh35,000 for subsistence operations to over Ksh87,000 monthly for commercial agriculture.

In early February 2026, the human cost of snakebite in Africa became devastatingly personal when Nigerian singer, Ifunanya Nwangene, died days after a snake bit her wrist as she slept in her ground-floor apartment in Abuja, Nigeria, where the hospital she was rushed to that Saturday morning did not have an effective antivenom.

Her death, which her grieving fans called entirely preventable, exposes the same fatal gaps plaguing Kenya: antivenom shortages, crushing treatment costs, and medical facilities unprepared for envenoming cases.

Nwangene’s death also shatters a dangerous assumption that snakebite is purely a rural, agricultural problem. Across the continent, the barrier between survival and death thus often comes down to geography, luck, and access to the right antivenom.

To make matters worse, Kenya does not produce scalable antivenom and imports between 10,000 and 30,000 vials annually from India and Mexico. This is not enough- the country needs about 100,000 vials annually. The imported vials are also not always effective against local snake species.

Traditional treatments, including sucking venom or cutting bite site, delay proper care

Research shows that many clinicians fear treating snakebite patients because they are unfamiliar with how to diagnose envenoming or safely administer antivenom. A 2021 study led by researchers Kieran Barnes and Cecilia Ngari in Kitui County, published in Toxicon X, found that even when health workers know what to do, they often lack basic equipment or reliable electricity to keep antivenom refrigerated.

These traditional treatments, including black stones, healing plants, tourniquets, sucking venom, or cutting the bite site, have not been proven effective and can cause serious harm by delaying proper care. Respondents reported death after a snakebite in 9.1 per cent of bitten community members and in 14.6 per cent of bitten family members.

Yet people turn to them for multiple reasons: accessibility, familiarity and affordability. Hospital care means hours of travel, uncertain availability of antivenom, and suffocating costs, besides affinity to traditions and beliefs.

Climate change threatens to intensify human-snake conflict, with Dr Oluoch noting that “when their habitats are destroyed, or prey becomes scarce due to drought, they venture closer to human dwellings.” Rising temperatures, extreme weather events, deforestation and agricultural expansion are all pushing snakes into closer contact with human populations.

Countries including Uganda, Kenya, Bangladesh, India and Thailand could face increased vulnerability to snakebites in the future, according to predictive modelling published in The Lancet Planetary Health. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has warned that climate-driven changes mean many communities will encounter new snake species they’re unfamiliar with, requiring urgent efforts to “future-proof” snakebite prevention and treatment strategies.

Treatment barriers include prohibitive travel distances and high treatment costs

“Our findings have important implications for how we plan and deliver interventions,” explained Prof Stienstra, who directs the African Snakebite Alliance. “Distributing antivenom, for example, is far more challenging when incidence differs so widely between regions.”

The healthcare-seeking data raises urgent questions about access and trust. The study points to multiple barriers: prohibitive travel distances, high treatment costs compared to traditional healers and deeply rooted cultural beliefs about snakebite treatment.

The mismatch between community reports and official health records creates another complication. When survey data was compared to the Kenya Health Information System, discrepancies ranged widely, from less than one per cent concordance in Trans Nzoia to 250 per cent in West Pokot, where official records exceeded survey reports.

These gaps stem from multiple causes: patients seeking care at facilities outside their home county, being transferred between facilities and counted twice, or returning for follow-up visits and being re-recorded as new cases. The implication is clear: Kenya’s health surveillance system needs standardisation to reliably track this disease.

Notably, the counties reporting the most snakebites in community surveys did not fully match official health records. Only two of the top five-Turkana and Kilifi-appeared in both lists. This suggests that the areas hardest hit by snakebites may also have the weakest health surveillance systems.

Kenya, Britain developing an antivenom tailored to local snake species

Despite these challenges, Kenya is taking action. The Kenya Snakebite Research and Intervention Centre, working with the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, is developing an antivenom tailored to local snake species that would need fewer vials to treat patients. The centre is also rolling out community education and testing new approaches, including mobile technology that links frontline clinicians to specialists in real time.

WHO has called for better integration of neglected tropical disease programmes to improve impact and cut costs. This study answers that call, showing that linking disease control with simple data collection can produce major results.

Snakebite was only recently recognised as a neglected tropical disease, and data across sub-Saharan Africa remains limited. WHO estimates East Africa’s incidence at 22.6 per 100,000, based on weak evidence. Kenya’s national rate of 36 per 100,000 suggests the true burden is higher.

Globally, snakebite envenoming causes more than 138,000 deaths and over 400,000 permanent disabilities each year.

Dr Oluoch hopes the data will guide policy, education and treatment. “Ultimately, we want this data to help prevent the thousands of injuries and deaths caused by snakebite envenoming.”