Schools with design flaws are ‘a big reason why learners with disabilities report low self-confidence, increased isolation, and high drop-out rates,’ Senator Crystal Asige.

Imagine a student who uses a wheelchair arriving at school, only to find a flight of stairs at the entrance and no ramp in sight. Or a blind learner who can’t navigate the narrow, cluttered hallways to get to class.

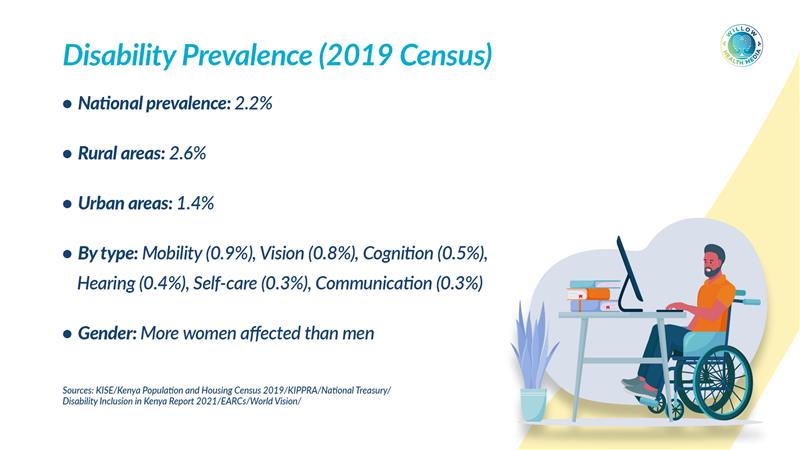

This is the daily reality for many Kenyan children with disabilities, and it’s a major reason why so many struggle with confidence, feel isolated, or drop out of school altogether. The 2019 census reveals that 2.2 per cent of Kenyans, approximately 900,000 people, live with some form of disability, with higher prevalence in rural areas where access to inclusive education is most challenging.

This is the problem Senator Crystal Asige is fighting to fix. She’s championing the My Learners With Disabilities Bill 2023, which would require all schools to become truly accessible. The law would make things like ramps, accessible bathrooms, and special learning tools not just a nice idea, but a mandatory standard.

In her verified X handle, she posted on August 23, 2025, that “Design barriers like multi-storey buildings without lifts, missing ramps, no accessible washrooms, narrow doorways, lack of assistive tools, or non-accommodative school transport are a big reason why learners with disabilities report low self-confidence, increased isolation, and high drop-out rates.”

Children with disabilities excluded from mainstream schools

Her mission underscores a profound crisis that persists despite substantial budget allocations, over Ksh970 million, and robust legal frameworks designed to guarantee inclusivity. A deep disconnect exists between policy and practice.

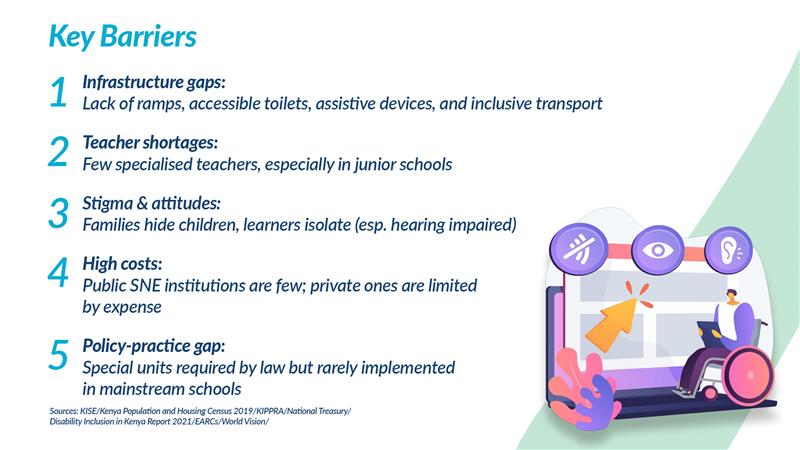

While Kenya’s laws promise inclusive education, children with disabilities continue to be excluded from mainstream schools due to a trifecta of challenges: inaccessible infrastructure, a critical shortage of specially trained teachers, and deep-seated societal stigma.

According to the Status Report on Disability Inclusion in Kenya (2021), the country has made notable achievements, including targeted infrastructure improvements and the establishment of 243 Community-Based Rehabilitation committees at county and sub-county levels. However, the implementation gap remains wide.

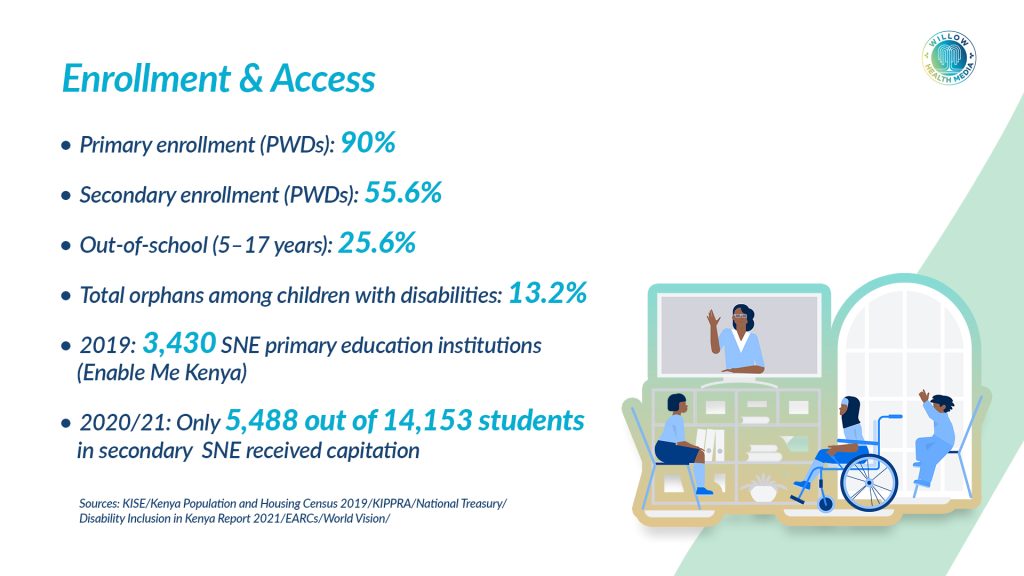

Enable Me Kenya, an organisation supporting persons with disabilities, reports that there were 3,430 special needs education teaching institutions at the primary level as of 2019. Yet the Kenya Institute of Special Education (KISE), which received Ksh647.61 million in the 2025/2026 budget, continues to face challenges in delivering services to remote areas despite intensifying its efforts.

According to Education Expert Johnstone Shisanya, these learners have “Special needs requirements, from care to infrastructure,” and their assessment is fundamentally different from the mainstream. However, he points to a simple yet profound economic barrier: “We have very few public special needs institutions, because they are very expensive.” This cost factor also discourages private investment, as entrepreneurs in education “want to minimise input but maximise output.”

Iten Special School has a culture of resource-sharing among teachers, departments

Facing these resource constraints, some schools are innovating. At Iten Special School, Head Teacher Lagat Joel has fostered a culture of resource-sharing among teachers and departments. “This enhances efficiency and promotes a more comprehensive educational experience for learners,” he explained. To bridge funding gaps, he proactively engages sponsors, parents, and NGOs like World Vision, which is currently improving water and sanitation facilities at the school.

Yet, experts like Shisanya argue that true inclusivity means integrating these learners into mainstream public schools, a mandate already enshrined in the Basic Education Act. He poses a critical question: the law stipulates “special units in all schools. But how many, even public schools, have special units?” The answer, he suggests, lies in a lack of resources, as these units demand “specialised teachers, specialised attention and specialised transport.”

This debate between dedicated special schools and full integration is central. Some experts, like Prof Samson Gunga of the University of Nairobi, believe dedicated schools can cause isolation. He advocates for integration so “fellow students would be sensitised,” though he acknowledges this requires “very strong follow-up and a large amount of resources.”

Lagat is a strong proponent of inclusive classrooms, where all students learn together with appropriate support. “This will reduce stigma, create a supportive environment where differences are valued, and lead to better collaboration,” he asserted.

The few specially trained teachers not posted to regular schools

A 2024 report from the Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA) on inclusive education in Kenya suggests integrated schools are larger, averaging 512 students compared to 200 in special primary schools, potentially offering a more vibrant social environment.

Beyond infrastructure, a severe shortage of trained specialists is perhaps the most immediate hurdle. Prof Gunga notes that even the few specially trained teachers are often not posted to regular schools, leaving them without the necessary expertise to support diverse learners.

Lagat confirms that while primary levels are somewhat staffed, there is a “pressing need for additional staff at the junior school level.”

The financial commitment is also inconsistent. In the 2020/2021 academic year, inadequate resources meant only 5,488 out of 14,153 students with disabilities in secondary special needs education received their full capitation funding.

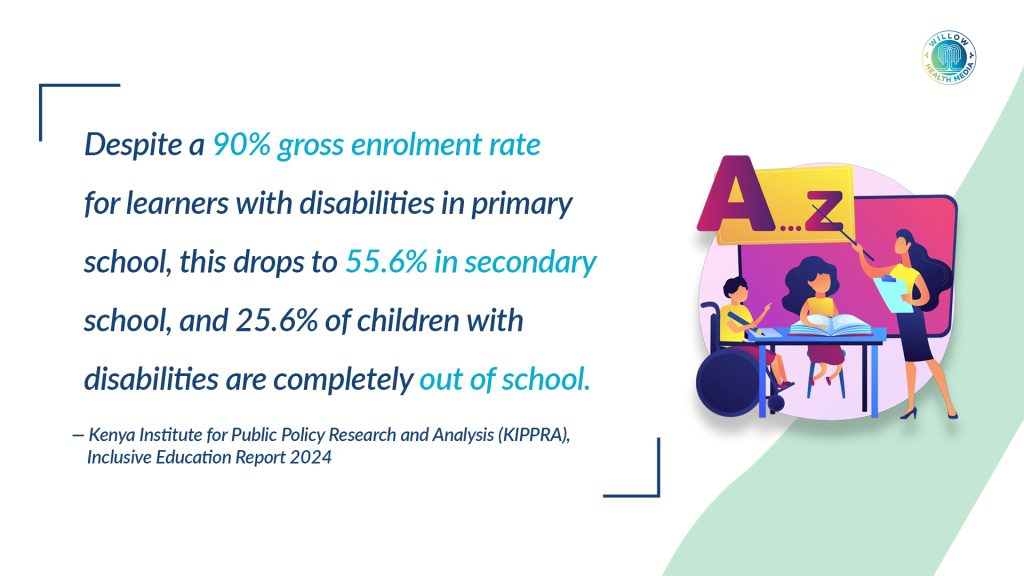

The government has made efforts, investing Ksh103.75 million in vocational training for learners with disabilities and achieving a 90 per cent gross enrollment rate at the primary level. However, this figure plummets to 55.6 per cent in secondary school, and an alarming 25.6 per cent of children with disabilities are entirely out of school.

Disabilities Bill mandates practical improvements like ramps, accessible washrooms

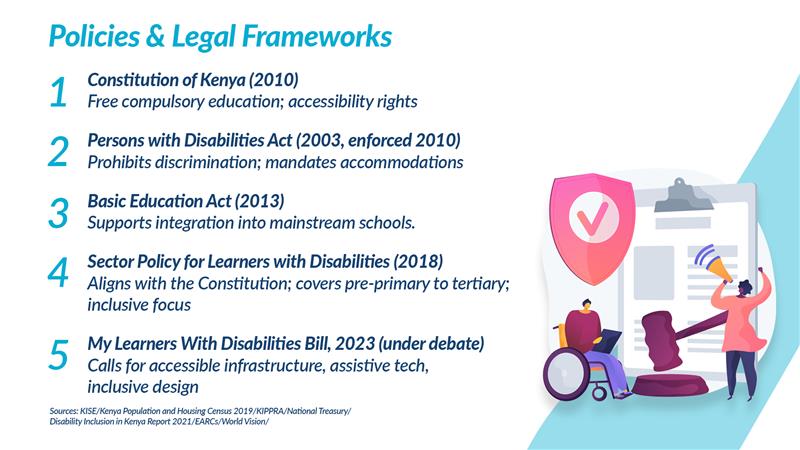

Kenya’s legal framework is strong. It is anchored by the Constitution (2010), which guarantees free basic education and accessible facilities; the Persons with Disabilities Act (2003), which prohibits discrimination; and the Sector Policy for Learners and Trainees with Disabilities (2018). The challenge, consistently highlighted by experts, is not a lack of laws but a failure in their implementation.

Embodying the push for tangible change is the My Learners With Disabilities Bill, 2023, which Senator Asige has vigorously championed. The bill, which was in its second reading as of mid-2025, mandates practical improvements like ramps, accessible washrooms, and assistive technologies, directly addressing the physical barriers she cited.

The 2025/2026 budget for Special Needs Education saw a slight increase to Ksh979.03 million for primary education, with significant portions allocated to key institutions. However, funding for special secondary schools was actually cut, from Ksh200 million to Ksh180 million.

Shisanya argues that solving the crisis requires shared responsibility: “resources from the Ministry, the community, because the government cannot give all.”

Ultimately, perhaps the most entrenched barrier is stigma. “The population is not sensitised about caring for the education of special needs people,” says Prof Gunga, noting some families still hide members with disabilities.

School pairs students with and without disabilities, helping them socialise

Lagat observes persistent negative attitudes that cause learners, especially those with hearing impairments, to isolate themselves. He highlights a communication chasm, as “most parents are unable to effectively communicate with their children who have hearing impairments.”

In response, his school pairs students with and without disabilities, helping them socialise and learn from each other’s strengths. This practical approach to inclusion is a microcosm of what is needed nationwide.

The path forward is clear. The Ministry of Education’s own 2025 report recommends making Kenyan Sign Language mandatory in teacher training, scaling up specialised programmes, and conducting a comprehensive assessment of all special needs schools. Initiatives like the INUKA sponsorship programme, which supports two students with disabilities from each county, are a start.

Kenya’s journey toward inclusive education hinges on a fundamental shift from writing policies to executing them. It requires targeted funding, a dedicated and well-deployed teaching force, and a relentless campaign to replace stigma with understanding. The future of hundreds of thousands of learners depends on the nation’s ability to finally translate its well-crafted intent into measurable, tangible results—tearing down both physical barriers and societal stigma to create a school system where every single child can learn and thrive.