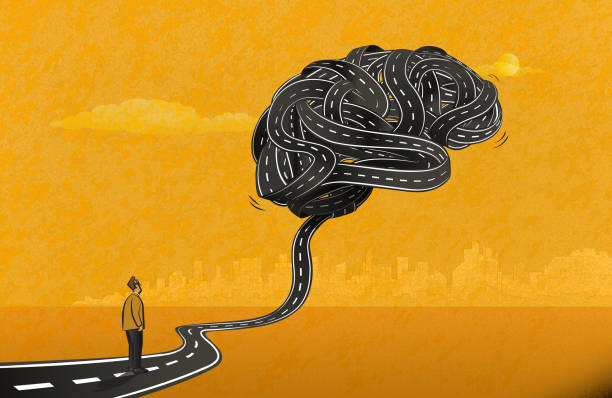

Sylvia Kemunto’s death was the fallout of fragile egos, buried emotions, a culture that mocks counselling. Where men fear therapy, rage festers. Where rejection bruises pride, violence follows. In this mix of silence and masculinity, neglected mental health issues among Kenyan men turn volatile.

On a quiet Sunday morning at Multimedia University, a light was extinguished too soon. Sylvia Kemunto, just 19, was found lifeless in a water tank. Her tragic story is a haunting reflection of the many systemic failures—not just in campus security or toxic masculinity, but in our collective neglect of mental health education.

Sylvia, a first-year Media and Communication student, was described by friends as “soft-spoken, humble, and devout.” But behind that gentle smile was a troubled relationship with a fellow student, Philip Mutinda, also 19. The relationship had reportedly been marked by emotional abuse and threats.

On the morning of her death, Sylvia’s roommate left for church. By evening, she would return to a scene of struggle. Days later, Sylvia’s body would be found. Mutinda, after fleeing to his rural home in Makueni, confessed. He had tried to force himself on her, but when she resisted, he pushed her. She hit her head, fell unconscious—and never woke up.

In his confession, Mutinda spoke of “rejection” as the trigger. But rejection isn’t a death sentence, it’s a psychological stressor—and in the absence of emotional maturity, therapy, or coping mechanisms, it can become deadly.

There have been many such tragic cases before. Remember Ivy Wangechi? She was the promising sixth-year medical student who was ambushed near Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital by ‘rejected’ admirer Naftali Kinuthia.

Armed with an axe and a knife, Kinuthia struck Ivy in broad daylight, before slitting her throat. He claimed he had been “rejected” after spending money and time pursuing her and in a twisted sense of entitlement, believed Ivy owed him affection. And when she didn’t reciprocate, he decided she didn’t deserve to live in 2019. The court found him guilty of premeditated murder, and in November 2023, he was sentenced to 40 years in prison.

There are other cases. Like that of Rose Owuor who was beheaded with a machete in cold blood in Nakuru after turning down a marriage proposal in 2016 from a man who had been aggressively pursuing her. This wasn’t passion but possession. The man who killed her did not love her — he tried to own her.

Toxic masculinity, emotional suppression, and the cultural rejection of therapy among men have created a volatile environment where emotional conflict too easily turns to violence

According to the Africa Data Hub, over 150 women were killed in gender-based violence incidents in 2023 alone, many of them by intimate partners. While the public conversation often focuses on the security and justice angles—as it should—it is time we ask a deeper question: What role does untreated, undiagnosed mental health distress play in these tragedies?

Data from the Kenya Mental Health Policy (2015–2030) revealed that more than 25 per cent of outpatients seeking health services in Kenya exhibit symptoms of mental illness. Mental health literacy remains low. Toxic masculinity, emotional suppression, and the cultural rejection of therapy among men have created a volatile environment where emotional conflict too easily turns to violence.

Research from the World Health Organization (WHO) indicates that about 70 per cent of men believe seeking help for mental illness is a sign of weakness. A study in the American Journal of Men’s Health identified stigma, perceived self-sufficiency, and lack of information about mental health resources as significant barriers as about 40 per cent of men reported seeking help for mental health as embarrassing.

A survey conducted by the Lancet Psychiatry in 2018 indicated that many Kenyan men have negative attitudes toward seeking mental health care due to perceived stigma and traditional masculine norms. The study revealed that only 13 per cent of men with mental health issues sought professional help, compared to 30 per cent of women.

Our education system focuses so much on academic excellence but continues to fail in one critical area: emotional intelligence. How many young men are taught to process heartbreak? How many young girls are equipped to navigate emotionally abusive relationships? How many students even know what a boundary looks like? We send teenagers into campus armed with textbooks, laptops, and career dreams—but not with the tools to handle life’s emotional trials. We hope they “figure it out.” Some don’t.

Educators must be trained to identify early warning signs of emotional distress, abusive tendencies, and mental illness

Kenyans must be proactive in dealing with the femicide crisis; first, by integrating mental health into the national curriculum. From primary school through university, mental health must be treated with the same seriousness as mathematics or English. Emotional literacy, conflict resolution, healthy masculinity, and relationship education should be part of life skills as early as possible.

Rwanda has successfully integrated mental health education into their school system post-genocide, leading to improved student behaviour and academic performance.

We should also train teachers and lecturers to spot red flags. Educators must be trained to identify early warning signs of emotional distress, abusive tendencies, and mental illness, such as understanding changes in behaviour, social withdrawal, aggression, and suicidal ideation. A partnership between schools and mental health organisations could offer cost-effective training modules.

Thirdly, normalise therapy in youth spaces—Kenyan campuses need on-site, full-time counselling professionals. Mental health should be destigmatised through peer counselling programs, student-led wellness clubs, and public talks by mental health advocates.

Beyond mental health, Kenya needs to implement legal reform and gender sensitisation. Young men must be taught—early and often—that rejection is not humiliation. “If a woman says no, walk away.” This message must be codified in school programs, faith-based teachings, and national campaigns.

What about parent and guardian involvement? Sylvia’s mother had already raised concerns with campus security. How many other parents are ignored or uninformed? Schools must create channels for parents to voice concerns, seek help, and remain involved in the lives of their children beyond academics.

The government can reduce stigma by launching campaigns to challenge stereotypes about masculinity and mental health, emphasising that seeking help is a strength, not a weakness. By expanding the availability of mental health services, particularly in rural and underserved areas, and developing anonymous helplines and online counselling services, it will ensure that men can easily access support without fear of judgment.

Women can help dismantle the stigma surrounding mental health by challenging harmful societal norms about masculinity

Sylvia’s story is not just about a girl who died—it’s about a society that failed her. It’s about a generation of young people navigating adult emotions with childlike tools. It’s about a young man who confused love with control, and rejection with defeat.

We cannot afford to mourn another Sylvia before we act. Every school, university, church youth group, and every household must now carry the responsibility of raising emotionally intelligent, mentally healthy individuals. Let us begin to teach our children, from the earliest days, that strength is not in domination, but in restraint. That heartbreak, though painful, is survivable. That no relationship is worth a life lost.

Women, who are often the bigger target of gender violence, can actively engage in community awareness campaigns that promote gender equality and challenge harmful societal norms about masculinity. By fostering open dialogues that encourage men to express their emotions and seek help, women can help dismantle the stigma surrounding mental health.

Additionally, women can support one another and advocate for access to resources such as counselling and shelters for those at risk of violence, creating a network of support that addresses both femicide prevention and mental health awareness.

We must hold the perpetrators fully accountable, change how society raises boys, and loudly reject the idea that women owe men anything for kindness, gifts, or affection. Love without consent is not love — it’s violence waiting to happen.

Dr Mutura Muchoka is an Oncology Pharmacist and Neglected Tropical Diseases and Surgical Conditions Coordinator, Department of Health, Meru County.