The bandits walked into the hospital, their weapons concealed, took out guns and rescued one of their renegade own. Patients took cover under beds, nurses fled. Where were the deter, detect, and delay measures?

Albert Chesang, a 52-year-old cancer patient, frail and struggling to walk, was admitted at the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) in Eldoret. Six days later, he vanished without a trace. The hospital refused to release surveillance footage to his family. A week after his disappearance, a senior security officer guided the family to his body, outside the hospital.

In Nairobi County, a 39-year-old, Gilbert Kinyua, a patient with a rare neurological disorder, was admitted at the Kenyatta National Hospital. Two months later, his throat was slit while asleep in his ward bed. The witness statement was never released. The investigation stalled; the killer remains unknown.

Elsewhere, a driver was carjacked and survived with a bullet wound. He was admitted to a level four hospital, but two days later, a gunman walked into the ward and shot the patient dead.

These are not episodes from a Hollywood thriller series, but real incidents with the murders of Kinyua and Chesang just days apart this February, exposing the extent of lapse in hospital security across the country.

Were the murders the result of administrative negligence or inside jobs?

Chesang’s sister recalls their nephew calling with news that ‘my brother was not in hospital’

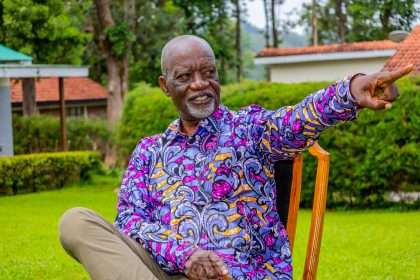

Willow Health visited Chesang’s family in Katalei village, Elgeyo Marakwet County and learnt that January 21, 2025, is a day they would wish to forget in a hurry. Just a week earlier, they had transferred Chesang to MTRH to seek better treatment. Chesang relied on his nephew for care as his siblings and neighbours took turns commuting from Iten to the hospital.

Beatrice Chepkemoi, Chesang’s sister, recalls their nephew calling with news that “my brother was not in hospital.”

The MTRH informed the family that Chesang was seen in the ward corridors the night before his disappearance, which the hospital reported to the police in Eldoret, kickstarting a search.

The family printed Chesang’s photos and distributed them, made Facebook posts and viewed unidentified bodies as far as Eldama Ravine.

“We went everywhere whenever we heard any news, but we weren’t lucky,” Charles Chesire, a neighbour, told Willow Health.

The ordeal took a painful twist when a senior security officer at MTRH called the family on January 27. He told them he had reviewed CCTV footage showing where Chesang died. According to Samuel Cheruiyot, Chesang’s cousin, the security officer led them through corridors within the hospital and a path outside the hospital compound towards a river.

The body looked cold, as if it came straight from the mortuary that same night, as there were no flies on it

At some point, the security officer leading the relatives stood to check his phone. The relatives, including Cheruiyot, took the lead in the path and just then, saw Chesang’s body: It had neither hands nor legs.

Cheruiyot recalled that from where they found the body, “It seemed like it had been dragged for about a metre. There were no signs of commotion before death. A few feet from the body, there was some fresh blood, but there were no flies around. The body looked cold as if it came straight from the mortuary that same night as there were no flies on it.”

Close to Chesang’s family is the Iten County Referral Hospital, where a daring rescue occurred in 2023 when an injured bandit sought treatment right in the middle of a government operation to rid the Kerio Valley of cattle rustlers and bandits.

Mark Kipsang, a clinical officer and an official at the Kenya Union of Clinical Officers, reported on duty just after the bandits had left. According to him, the bandits had walked into the hospital and headed for the wards, their weapons concealed. Once inside, they took out their guns and rescued one of their renegade own.

“Patients took cover under the beds and nurses fled the wards in fear of their lives because they were ready to shoot. In that melee, the bandits took off through one of the chain-link fences,” Kipsang told Willow Health.

Two years after the incident, the Iten County Referral hospital has undertaken some measures to improve security: CCTV cameras have been installed, chain-link and iron-sheets fence most parts of the facility while security officers staffing the hospital were increased.

“We also have a good relationship with the National Police Service so that in case of any incident, we are able to communicate and have it sorted out,” said Lawrence Kogo, the Medical Superintendent at Iten County Referral Hospital.

We offer services from ward to ward, and we are not safe. If someone is planning something ill, they might get you

Kipsang, however, notes that the safety of both health workers and patients in the hospital is not guaranteed as “The ratio of the security officers working here is wanting. At any given time, you will find them in one area. We offer services from ward to ward, and we are not safe. If someone is planning something ill, they might get you,” he warns, adding that the Iten Hospital deserves a stone wall equipped with CCTV and a permanent deployment of police officers.

Benson Biwott, a nurse at Iten County Referral Hospital, echoed Kipsang’s concerns, arguing there is an acute shortage of healthcare workers and an increase in number would improve security but presently “you can find one nurse in a ward of about 40 patients.”

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a 2.5:1,000 medical staff to population ratio for adequate coverage of primary care interventions, but many studies call for more nurses. In the US, for instance, the State of California has long legislated nurse to patient ratios with staffing at medical-surgical wards being 1:5 nurse to patient ratio. Critical care and other specialized areas have more stringent ratios.

“In a medical ward, one nurse should cater to six patients; in a surgical ward, you are supposed to have five patients,” said Biwott.

Biwott and Kipsang argue that having adequate healthcare workers employed in a healthcare facility has a bearing on the security of both healthcare workers and patients.

Poor state of security in hospitals goes against the constitutional right to life and security

“There is no day the security person manning the area is offering a service. They are placed at strategic places like the gates or the exits. So, our lives as well as our patients are not guaranteed,” said Kipsang.

Yet the hospital is responsible for providing security to the healthcare workers and patients.

Nelius Njuguna, a lawyer and programme officer at Kenya Human Rights Commission says the poor state of security in hospitals goes against the constitutional right to life and security for all citizens under Article 29 and which “provides that you should be free from all forms of violence either from public or private sources,” she said.

Njuguna, who has been following up on Kinyua’s murder case at the Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH), reckons the hospital has full responsibility in case a patient loses their life or is injured while in their care. This is because hospitals owe patients the duty of care to protect and prevent any incidents, explains Njuguna.

While the security in hospitals like Kenyatta is wanting, there have been recent improvements, according to Dr Kenneth Oluoch, a strategic security expert who has consulted there before.

He says Kenyatta National Hospital now has “the security and safety manager who heads that security function” besides professionally reorganizing other departments dealing with security.

Dr Oluoch blames the recent killings at KNH on possibly ignoring security measures from experts’ recommendations of security is not prioritized as a function.

Dr Oluoch, the Director of the Kenya School of Security Management, told Willow Health that everything within a hospital needs protection, thus elevating the role, meaning “Security should be a function of the executive and anybody managing security should actually belong to the C-suite.”

The old architecture of most Kenyan hospitals doesn’t help in security matters

Major (Rtd) Peter Kala, a security and risk management expert, reckons that the architecture of most hospitals, including Kenyatta National Hospital, doesn’t help matters and that security experts need to be involved during construction “As part of the project management team to conceptualize building access. But some of these hospitals were built a long time ago and it becomes difficult to loop in security measures needed for countering emerging threats.”

Major Kala also singles out the reluctance by hospital management to budget for security, which “shouldn’t be taken as a last option. In fact, security of people, property and resources should come first.”

To meet the standards, he explains, a hospital needs three levels of security: The outer layer, according to Major Kala includes a proper perimeter wall, preferably 2.4 metres and above, with a functional electric fence. The middle layer has aspects of access control with guards, metal detectors and contraband checks.

“Here we are doing the actual access control. Who is going where? To do what? Which are the restricted and unrestricted areas? What do you have which identifies you?” he elaborates.

The inner layer, according to Major Kala provides the last barrier to breach of security. “If you are supposed to go the X-ray department for example, you should not go to the maternity ward. But you find that at the last layer, people are able to access any other area within the hospital, and that is where the problem begins.”

To address the issue of hospital security in Kenyan hospitals, Major Kala said security measures should be a deterrent to breaches. Secondly, hospital security should allow for the detection of breaches, and thirdly, they should be able to delay the breach or the advancement of an adversary. Lastly, the security measures should be able to deny access to a breach.

“All these deter, detect, delay measures are made to deny an adversary from reaching his objective,” he said.

Security sector still stuck in the traditional security services for decades

According to Dr Oluoch, the security sector also takes the blame for its wanting levels of service and dire need for research, innovation and creativity as most are “stuck in the traditional security services for decades. They are stuck at a guarding level. They are stuck at the rapid alarm response level. There is no new thinking. There is very minimal attempt to do research and even creativity.”

Then there are regulatory and policy challenges guiding training, and Dr Oluoch says Kenya currently has three different curriculums for training of security personnel making the achievement of a standard course impossible. The National Industrial Training Authority, the Private Security Regulatory Authority and the Ministry of Education’s TVET, all have separate curriculums and “until that one is sorted out, we cannot talk about quality,” said Dr Oluoch.

There are internationally accepted best practices in hospital security. One study found that best practice strategies exist in areas of “communications, coordination, building design, space adaptability, and patient routing that can be shared and incorporated into the healthcare preparedness efforts in all three countries”

Dr Oluoch, however, says different countries have varying security needs. Some are military states while others are barely policed, and “the best is to understand ourselves, innovate solutions that meet our unique needs”, and then borrow a few things to “augment what we’re really doing right.”